The Canadian government raised concerns over the European Union’s regulations on chemicals on more than 20 occasions over the course of a decade, according to a letter seen by Energydesk.

In a note sent to the Belgian government on October 19, the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL) claims that the Canadian state challenged the EU’s REACH regulations at the World Trade Organisation 21 times between the years 2003 and 2011.

The UK’s Health and Safety Executive (HSE) describes the REACH regulations as providing “a high level of protection of human health and the environment from the use of chemicals.”

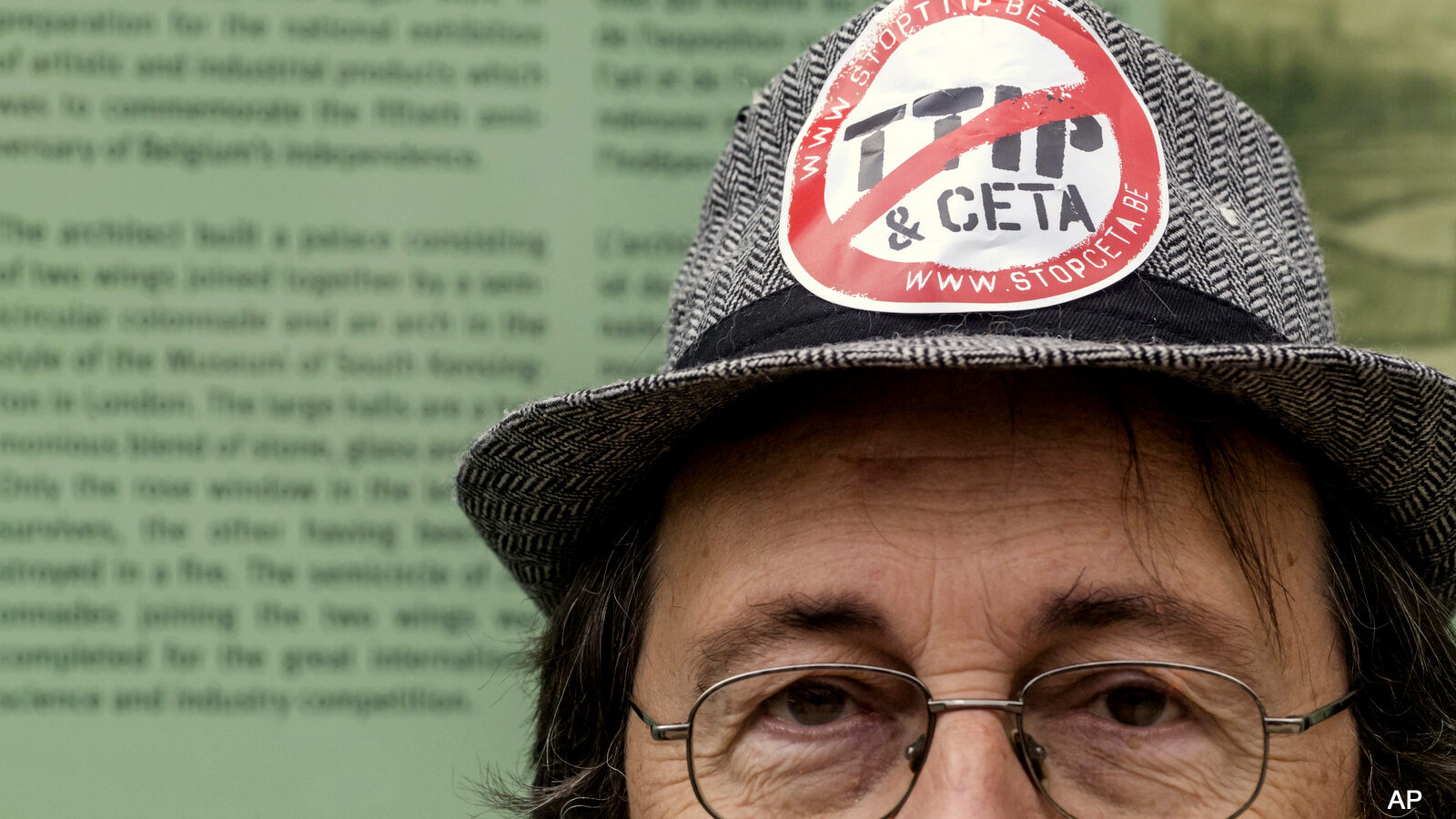

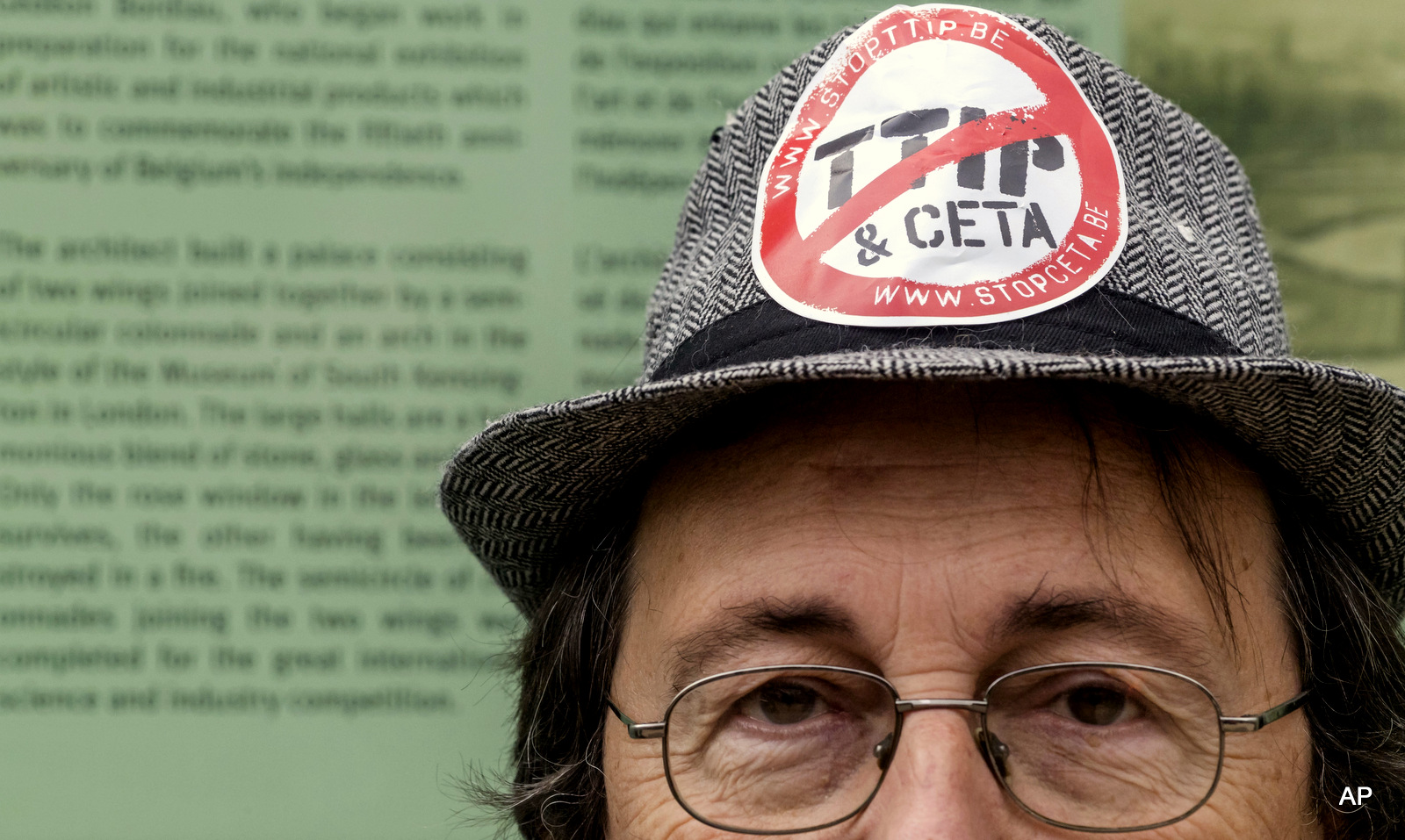

The news will raise concerns that Canadian companies may use the trade and investment deal CETA to undermine EU regulations.

“The threat of undue Canadian influence on environmental regulations such as REACH is real,” CIEL CEO Carroll Muffett wrote.

The CETA deal – which sets up private courts that enable foreign corporations to sue countries – has been held up by the British government as a model for post-Brexit free trade deals.

Corporate courts

Canadian companies have also used the trade agreements to take legal action against countries on 42 occasions, according to data from the Investment Policy Hub — with Canada ranked 5th among the nations in which this type of investor-to-state lawsuit have been filed.

Earlier this year, for example, the Canadian pipeline company TransCanada sued the United States government for $15 billion over its decision to scrap the Keystone XL project — using a provision in the NAFTA trade deal.

CETA, which is currently being signed by EU members following a week-long blockade by Wallonia and two other Belgian regions, sets up an investor dispute system called the Investment Court System (ICS).

In fact the ICS was among the reasons that the Wallonian government took a stand, with the region’s leader Paul Magnette saying: “I would prefer that [the ICS] disappears pure and simple and that we rely on our courts or at the very least, if we want an arbitration court, it must provide equivalent guarantees to domestic ones.”

As part of the newly negotiated agreement, the Belgian government will ask the European Court of Justice to rule on the legality of the deal — and the ICS in particular.

Beyond REACH

REACH – the registration, evaluation, authorisation and restriction of chemicals – is a set of extensive rules “adopted to improve the protection of human health and the environment from the risks that can be posed by chemicals” — so says the European Chemicals Agency.

Canada’s concerns – which were not formal actions, but rather issues raised at the WTO – largely related to rules around competition and whether the regulations would be burdensome to business.

The 21 complaints spanned the administrations of the Liberal Paul Martin, when REACH was just a draft, and the Conservative Stephen Harper.

Essentially Canada – like the United States – takes issue with the European approach to regulation, which is described as the ‘precautionary principle’.

This approach means products need to be proven safe by companies who seek to market them, before they enter the market. In North America, the burden of proof is on public authorities, which have to prove that a product is dangerous.

Documents unearthed by CIEL show that Canada has filed objections to the EU using this approach to regulate endocrine disrupting chemicals, arguing that the “EU’s hazard-based approach could unnecessarily disrupt trade in food and feed”.

Scientific studies show a range of health impacts caused by exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals – which are found in food containers and plastics – including IQ loss and adult obesity.

This work by Energy Desk is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike International License.

This work by Energy Desk is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike International License.