NAIROBI, Kenya — Soon after the end of the M23 rebellion that threw parts of eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) into conflict for much of the last two years, a blog post titled “We Stopped M23” appeared on the website of a California-based nonprofit called Falling Whistles.

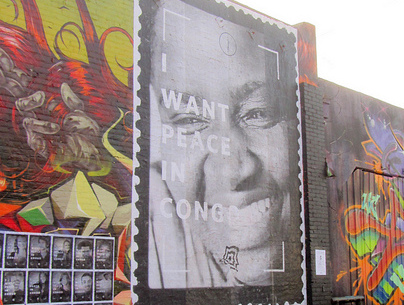

The slick homepage describes the organization as “a campaign for peace in Congo.” It urges visitors to “be a whistleblower for peace” by purchasing stylish metal whistles, hung on a chain or black cord, from the organization’s online store.

You’ve got options: A brushed copper whistle will set you back $58. The cheapest is $38, while the clearly popular “Gunmetal” whistle, currently out of stock, costs $48. Part of the profit from the whistle sales supports grassroots work in Congo.

The group’s latest advocacy project is #StopM23, which has encouraged supporters to use Twitter and Facebook to demand that the United Nations and the White House end violence in the DRC.

Falling Whistles is a product of the online activism zeitgeist that has produced countless click-your-support petitions like — most famously — last year’s Kony 2012 campaign.

But does any of it actually work?

Ugandan Joseph Kony, leader of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), is still at large, still kidnapping children and still terrorizing villagers more than a year after Invisible Children’s #Kony2012 campaign and video became an internet phenomenon.

Last week the online activist group Avaaz ran a petition in Kenya under the banner #JusticeForLiz, seeking the arrest and prosecution of a gang of brutal rapists whose official punishment — they were made to spend a morning cutting grass — sparked widespread outrage.

Despite nearly 1.4 million petition signatures, however, Kenya’s chief of police has dampened hopes of justice being done.

In the case of #StopM23, the question is not whether the rebellion has ended. It’s whether Falling Whistles really played much of a part.

Most analysts agree that a series of UN reports detailing Rwanda’s connections with M23, combined with the humanitarian crisis triggered by the fighting and last November’s rebel takeover of the DRC city of Goma, are what drove the actions.

But Falling Whistles argued that “what was needed to tip the scales was a large public outcry.

“Less than a year since we joined together to #StopM23, the rebel group has been defeated,” the company said last weekend as rebels fled an unusually effective assault by the Congolese army backed by UN peacekeepers.

Falling Whistles claimed its campaign, which involved “bombarding the US ambassador to the UN with thousands of tweets,” had “worked” by pushing Washington to suspend some aid to Rwanda, the country widely accused of backing the M23 rebellion.

As evidence of the role they played, the organization noted that the hashtag #StopM23 “trended on Twitter in the United States over the course of 24 hours.”

The reaction from many who know the region — and its conflicts — was as fast as it was scathing.

“The narcissism of this reaches a wholly new level, even for US clicktivism,” one long-standing Africa correspondent wrote on his Twitter feed.

Another correspondent, who lived in the capital Kinshasa until recently, tweeted a link to the blog post with the comment, “Errr, WT very F??”

The nonprofit appeared to claim credit for a string of developments that made the M23’s defeat possible: President Barack Obama’s decision to appoint a special envoy to the region, the UN Security Council’s decision to deploy a new, more aggressive UN brigade, and the implementation of much-needed reforms to Congo’s abysmal army.

Three days after posting the blog, Falling Whistles seemed to realize the hubristic tone of its celebratory post had not gone down well.

“Here’s what Falling Whistles meant when it said ‘We Stopped M23,’” advocacy director Monique Beadle began.

She went on to list a series of clarifications, particularly about who Falling Whistles understands “we” to be. Many actors — Congo’s army, UN peacekeepers, the US State Department, and refugees, journalists, donors — along with “Whistler Society leaders” and supporters in countries around the world “united to Stop M23,” Beadle wrote.

In emailed responses to GlobalPost, Sean Carasso, the 31-year-old who founded Falling Whistles after traveling to the DRC in late 2007, stood by the claim that the campaign, as part of a coalition of advocacy organizations pressuring the US government to act, contributed to the end of the M23.

“The Envoy, the aid cuts, and the public pressure on Rwanda were all important aspects to the events of the last few weeks,” said Carasso, referring to M23’s rapid military losses. “Those were things we promoted in public and in private, and we’re relieved to see that they contributed to the downfall of M23.”

Carasso acknowledged the limitations of tweeting-for-change, but said he believes strongly in its power.

He pointed out that around 18 percent of the money raised from over 80,000 whistle sales has gone to local activists and organizations in eastern Congo.

“Look, I know as well as anyone else that 140 characters from a single person isn’t going to change anything immediately,” he said.

“But thousands (or millions) of people saying the same thing, in unison, in a single week? That’s powerful.”

This article originally appeared in GlobalPost.