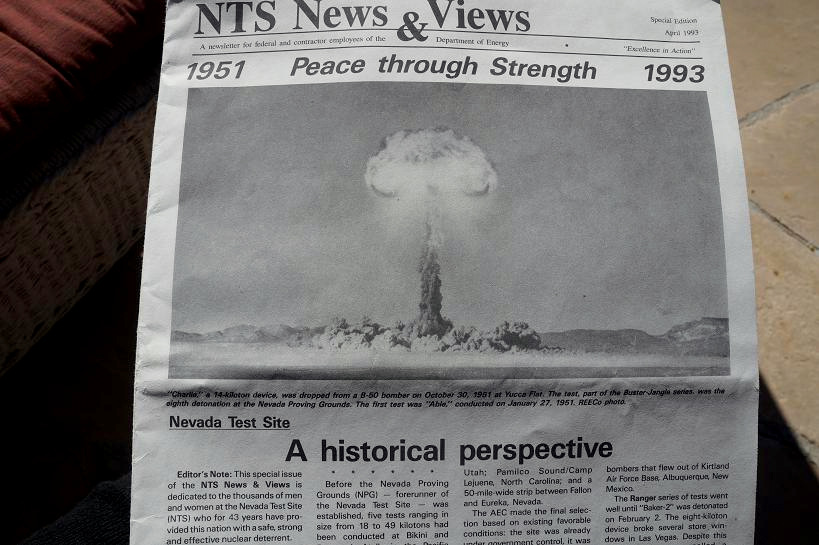

NYE COUNTY, Nevada — From 1951 to 1992, the U.S. government used a 1,300-square mile patch of land known as the Nevada Test Site for atmospheric and underground nuclear weapons testing. Many people have seen images from the site, though they probably don’t even realize it: 928 American and 19 British nuclear tests were conducted there, and it’s the place where the infamous mushroom cloud images were taken.

Today, tourists can take a trip back in time to the Cold War with a visit to the National Atomic Testing Museum. Located in Paradise, Nevada, south of the test site, the museum features permanent exhibits on surviving a nuclear blast and life in the “Atomic Age.” And for those who have grown weary of the nuclear reality back on Earth, there’s also an Area 51 exhibition — “Area 51: Myth or Reality?”

What’s mostly absent from the exhibition space, however, is attention to the global movement against nuclear weapons and the impacts on the nearby environment and people, including the Western Shoshone and Moapa Paiute.

The Moapa River Reservation is downwind of the Nevada Test Site, and locals have long maintained that radiation has harmed the health of the local population.

“We hope that that stuff [radiation] went up in the air and blew over us,” Vernon Lee, a Southern Paiute with the Moapa Band of Paiute Indians, who has lived on the Moapa River Reservation since 1973, told MintPress News. “We know that we got some because we are just east of the testing, but we hope we got less.”

Areas around the test site, particularly those located “downwind,” saw increases in cancers, including leukemia, lymphoma, thyroid cancer and brain tumors, throughout the entire span of the nuclear weapons testing. A 1984 study by the Journal of the American Medical Association found increased rates of cancer among Mormon families as far away as southwestern Utah, for example.

For Lee, the decades of environmental degradation and risks to human health reflect a much larger issue. The problem, he believes, is that the U.S. government does not recognize the tribal nations as equals. Officially, the U.S. Department of Interior states that the U.S. government operates under a “federal Indian trust responsibility,” a legal obligation that includes “moral obligations of the highest responsibility and trust” toward Native American tribes.

“To me, that doesn’t exist. It’s a word on paper, but I don’t think I have ever seen it put into practice,” Lee said.

“Trust responsibility, to me, is that government-to-government relationship that they are supposed to have with the tribes. It’s ridiculous the way the U.S. government treats the sovereign tribes. It’s very unfair.”

Native communities have a long history of resources discovered beneath the reservations being exploited by the U.S. government and supported industries. These communities have suffered exposure to dangerous substances through uranium mining and milling. In Nevada, the lives of generations of Western Shoshone and Moapa Paiute have become intertwined with the history of nuclear weapons testing and, more recently, the disposal of nuclear waste from faraway power plants.

“There are multiple problems. Moving the waste is a problem. High risk, unnecessary risk. If the company is ever going to benefit from nuclear power they should process it and store it themselves. Stop shipping it across the country and exposing the population to a potential disaster,” Lee said, alluding to the controversial long-term nuclear waste repository planned for Yucca Mountain, about a three hours’ drive from the reservation.

The battle for Yucca Mountain

Commercial nuclear power plants produce spent nuclear fuel, a radioactive byproduct. High-level radioactive waste is also produced as spent nuclear fuel is reprocessed into material for nuclear weapons. Disposing of both of these byproducts is a difficult and dangerous task.

In response to growing concerns over nuclear waste storage, Congress passed the federal Nuclear Waste Policy Act in 1982, which charged the Department of Energy with finding a place to build and operate a geologic repository, or underground nuclear waste disposal facility. Operating on the notion that the safest way to dispose of the waste is to bury it in rock deep underground, the DOE studied several sites for a possible geologic repository before settling on Yucca Mountain, located 100 miles northwest of Las Vegas.

The plan for the Yucca Mountain Nuclear Waste Repository had the support of President George W. Bush, but met with opposition from Nevada state officials and environmental and Native activists, who fear that the rock at Yucca Mountain will not be able to contain nuclear waste for long periods of time.

In 2009, environmental and anti-nuclear organizations, including Beyond Nuclear, Greenpeace, Center for Health, Environment & Justice, and the International Society for Ecology, sent a letter to President Barack Obama calling the selection of the Yucca Mountain site “a purely political decision.” They argued that it has been been evident since 1992 that the site “could not meet the EPA’s general radiation protection standard for repositories.”

Obama opted to end funding for the project, setting off an ongoing legal battle. In August 2013, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia ordered the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to approve or reject the DOE application for the proposed waste storage site at Yucca Mountain. The Associated Press reported:

“In a sharply worded opinion, the court said the nuclear agency was ‘simply flouting the law’ when it allowed the Obama administration to continue plans to close the proposed waste site 90 miles northwest of Las Vegas. The action goes against a federal law designating Yucca Mountain as the nation’s nuclear waste repository.”

In January 2015 the NRC concluded that the DOE’s license application for Yucca Mountain satisfies nearly all of the commission’s regulations. The commission must now clear all challenges from the state of Nevada and Native communities, a process which could take several more years.

Then, in August, the NRC released a supplement to the DOE’s 2002 and 2008 environmental impact statements for the planned nuclear waste repository. The NRC’s report evaluates different potential radiological and non-radiological impacts on the environment, soil, and public health, and the potential for disproportionate impacts on minority or low-income populations. The NRC wrote:

“…[T]he NRC staff finds no environmental pathway that would affect minority or low-income populations differently from other segments of the general population. Therefore, the NRC staff concludes that no disproportionately high and adverse health or environmental impacts would occur to minority or low-income segments of the population in the Amargosa Valley area.”

The nonprofit environmental advocacy group Natural Resources Defense Council disagreed, stating that the NRC “still adheres to the flawed assumptions the DOE used to frame the foundation of its analysis of potential environmental impacts of the repository.”

As this process drags on, two companies are providing interim storage sites for the country’s nuclear waste. One is located in Andrews County, Texas, and owned by Waste Control Specialists. The other is an underground storage site in Southeastern New Mexico, operated by Holtec International and the Eddy-Lea Alliance of New Mexico. Waste Control Specialists are hoping to turn the temporary West Texas facility into a long-term waste storage site.

An act of genocide?

About 90 miles from the money and vices of Las Vegas, Ian Zaparte stands at the base of Yucca Mountain, discussing the history of theft of Shoshone land and the threats posed by the Yucca Mountain Nuclear Waste Repository.

Zaparte represents the Western Shoshone traditional government and has been fighting in defense of his community and the planet for 30 years.

The Western Shoshone are one of 12 Indian nations whose chiefs signed the Treaty of Ruby Valley with the governors of the Nevada and Utah territory in 1863. In addition to recognizing the sovereignty of each of the Indigenous nations, the treaty gave the Indian nations ownership over millions of acres of land in Idaho, Nevada, California and Utah. It also allowed settlers access to the land for gold mining and homesteading, but did not give them title.

However, a history of land grabs through controversial legal means saw that land handed over to various agencies of the U.S. government, including the Bureau of Land Management. In 1979, the U.S. put $26 million in a fund for the Shoshone for title to 24 million acres, but the tribe declined the money. The Supreme Court ruled six years later that the settlement, whether officially accepted by the tribe or not, extinguished the Shoshones’ claim to the land.

Essentially, the U.S. government has stated that encroachment upon Indian lands by settlers, railroads, telegraphs, ranches and gold mines extinguished the Shoshone claim to the land. In 2006, the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination found “credible information alleging that the Western Shoshone indigenous people are being denied their traditional rights to land.”

According to a University of Michigan Environmental Justice Case Study:

“The Western Shoshone argue that the basis of this plenary federal power is rooted in the colonial arrogance of the 17th century, and the laws that gave the United States Government control over the Native Americans are ‘extensions of Christian claims to world supremacy.’”

Since the Western Shoshone have lost claims to their traditional lands, the U.S. government is free to use the land for projects, such as nuclear weapons testing and the Yucca Mountain Nuclear Waste Repository.

Zaparte says the NRC and the DOE are ignoring the possibilities for danger in the area and denying the impact the Yucca Mountain Nuclear Waste Repository would have on local communities, including the Paiute and the Shoshone.

“There are 26 faults, seven cinder cone volcanoes, 90 percent of the mountain is saturated with 10 percent water,” Zaparte told MintPress. “If you heat the rock, it will release that water. If the water comes up and corrodes the canisters, it will take whatever is in storage and bring it into the water and into the valley.”

The DOE is currently accepting public comment from communities, states, tribes and other stakeholders on how to establish a nuclear waste repository with respect to the community. The DOE says it aims “to establish an integrated waste management system to transport, store, and dispose of commercial spent nuclear fuel and high level defense radioactive waste.” The public comment period ends on June 15, and the DOE and Nuclear Regulatory Commission will likely issue statements shortly after.

Although the Yucca Mountain project has stalled during the Obama administration, a new president, especially a nuclear-friendly president, could theoretically rally for funding of the Yucca Mountain Nuclear Waste Repository. The timing of the DOE’s study could potentially make the Yucca Mountain a topic of debate in the 2016 presidential election.

Still, for Zaparte, the actions taken by the U.S. government so far constitute an act of genocide against the Western Shoshone and other tribal nations who have been subject to the effects of nuclear testing and power. He is determined to fight for his people’s way of life and the land that his ancestors fought for.

“We have a deliberate act by the United States to systematically dismantle my living life ways for the profit of the nuclear industry and the benefit of the United States,” Zaparte said. “At the worst, this is genocide under the U.N. Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide.”

‘We just call it a chemical soup’

Just as the Yucca Mountain nuclear waste dump struggles to come into being, local activists have forced the closure of a coal-burning power plant that was responsible for pollution.

Vernon Lee, of the Moapa Band of Paiute Indians, used to work at NV Energy’s Reid Gardner Generating Station, located near the northeast corner of the Moapa River Reservation. He believes he was fired “because of my issues with pollution and safety.”

Though he says that, legally, the blame can’t be placed on NV Energy, “everyone believes” the company is responsible for local air pollution.

“If you are around here breathe some of that air, it comes in like a fog bank, huge white clouds coming at us,” Lee said. “It’s bad stuff. We just call it a chemical soup. When it dries the wind will pick it up and carry it over here.”

Last summer, the Moapa Paiute forced NV Energy into a settlement of $4.3 million in a 2013 lawsuit seeking damages for the pollution caused by the Reid Gardner plant. Tribal Chairman Darren Daboda previously said the funds would be used to build a wellness center and install air pollution monitors.

The lawsuit was filed by the Paiute with support from the Sierra Club and demanded that NV Energy come up with a plan to safely remove coal ash, a hazardous byproduct of coal power plants. So far, three of the four units at Reid Gardner have been shut down, and the final unit is scheduled to close in 2017. The plant is shutting down as the state moves away from coal and toward alternative energy such as solar plants.

Lee says his views on the environmental dangers are based on his experience at the plant:

“We used to take asbestos. They would clean it up properly and tell us to take it to the top of the hill and put it in the asbestos dump. At that point they would just say cover it up. The stuff was bubbling and you could see it going into the air. So the truth is they did everything properly on paper but in reality it was much different. And that was just with asbestos.”