MINNEAPOLIS — MintPress News is proud to host “Lied to Death,” a 13-part audio conversation between famed whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg and social justice activist Arn Menconi.

Menconi wrote that these interviews are a “mixture of historical, political science and Dan’s sixty-year scholarly analysis as a former nuclear planner for Rand Corporation.”

For more information on the interview and Ellsberg, see the introduction to this series.

Chapter 7: ‘Nixon was threatening and planning a bigger war’ in Vietnam

During the Vietnam War, the U.S. government dropped almost 8 million tons of bombs, and, in this chapter of “Lied to Death,” Ellsberg recalled his shock upon learning that much of that ordinance was used long after the war was clearly being lost.

On Jan. 30, 1968, the North Vietnamese army and the Viet Cong launched the massive Tet Offensive, named for the Vietnamese New Year, which is when the attacks began. It was a devastating coordinated attack that produced major setbacks for U.S. forces and the South Vietnamese government.

It also prompted a turning point in U.S. opinion about the war. Walter Cronkite, the highly respected TV journalist, famously closed a February 1968 CBS News broadcast with these words:

“For it seems now more certain than ever, that the bloody experience of Vietnam is to end in a stalemate. To say that we are closer to victory today is to believe in the face of the evidence, the optimists who have been wrong in the past.

To say that we are mired in stalemate seems the only realistic, if unsatisfactory conclusion.”

In 1967, President Lyndon Johnson was so shaken up that he met with prestigious military officials, known as the “Wise Men,” who advised him to broadcast more positive reports from the losing war. While creating positive propaganda about the war efforts in the media, Johnson dramatically increased the number of bombs dropped: Ellsberg said 4.5 million tons of bombs were dropped after the losses at the Tet Offensive.

Despite this strategy, the U.S. continued to lose, and Richard Nixon won the 1968 presidential race based on the idea that he’d end the war in Vietnam as quickly as possible.

Ellsberg said Nixon believed he could win the war quickly by issuing a nuclear ultimatum to Vietnamese forces and offering a treaty which would offer concessions from both sides.

“There was pressure to make the war larger” if the offer was rejected, the whistleblower noted, and “nuclear targets were picked.” Ellsberg speculated that the plans would have gone ahead in November 1969.

Instead, a huge demonstration on Oct. 15, 1969, the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam, combined a general strike with nationwide protests and teach-ins. About 2 million people came out to protest across the country, even “little towns that had never protested before,” Ellsberg recalled.

This was a major success of the anti-war movement, even though most of its members were never aware of their victory.

“As far as you could see from the anti-war movement, it had almost no perceivable effect,” he said. “The war went on.”

However, Ellsberg concluded:

“People didn’t understand the Joint Chiefs were pressing throughout this period for a bigger war, and Nixon was threatening and planning a bigger war.

It did not shorten the war significantly, but it did keep a lid on the war. Without the Moratorium, there would have been an escalation, possibly the use of nuclear weapons in November 1969.”

Listen to Chapter 7 | Nixon was threatening and planning a bigger war’ in Vietnam:

https://soundcloud.com/arnmenconi/lied-to-death-conversations-with-daniel-ellsberg-chapter-7?in=arnmenconi/sets/lied-to-death-conversations

About Daniel Ellsberg

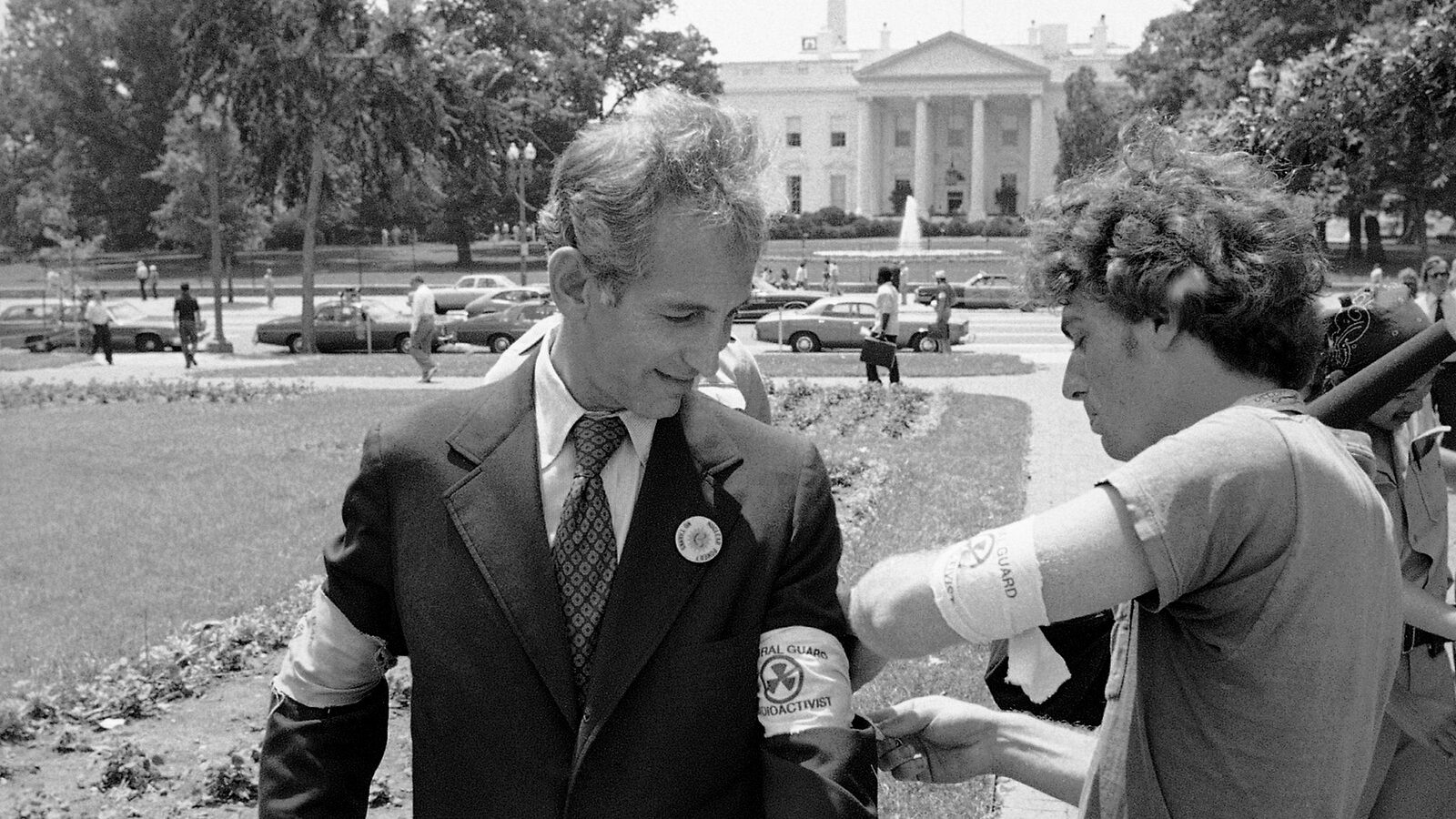

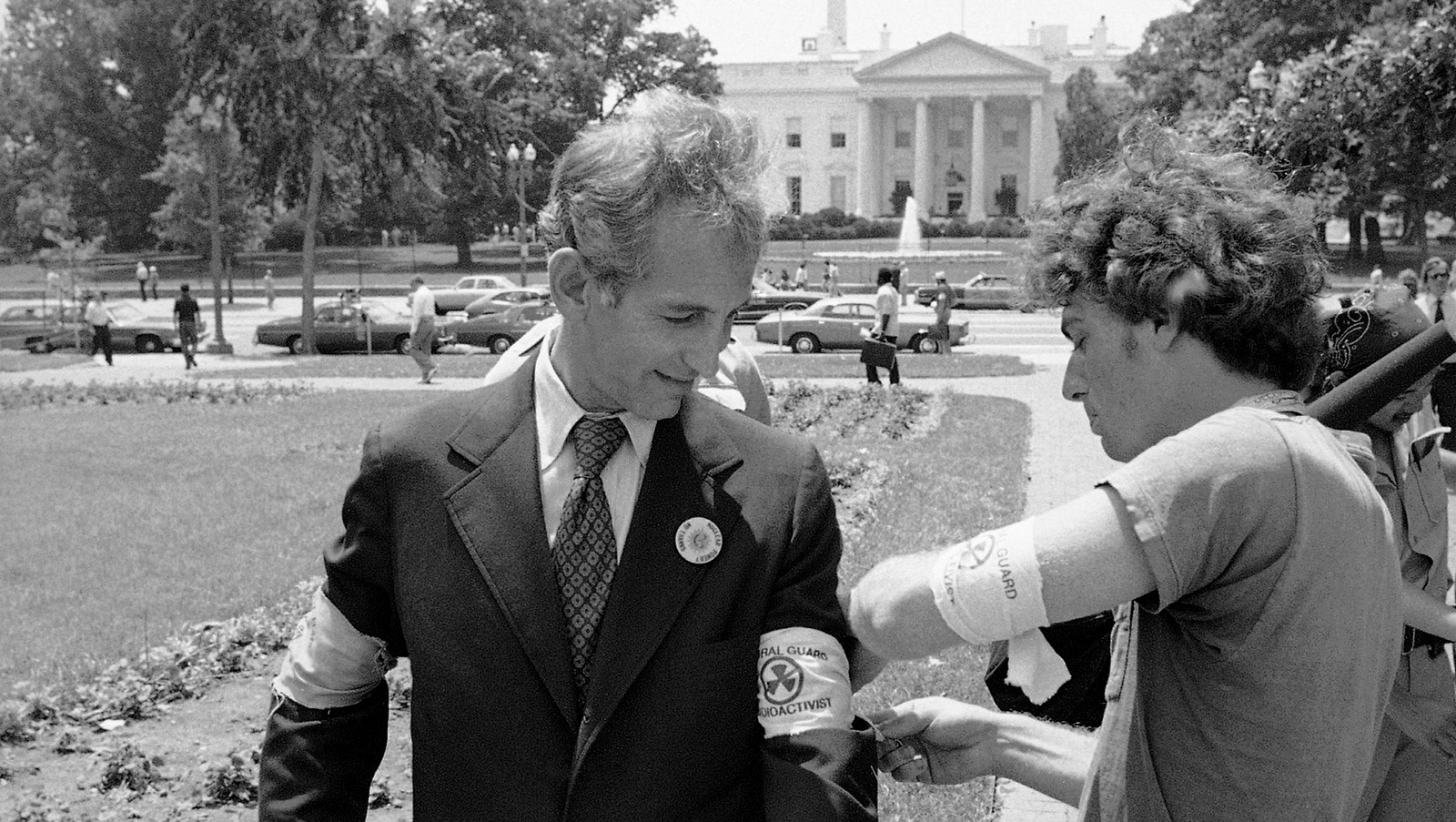

As sites like WikiLeaks and figures such as Edward Snowden continue to reveal uncomfortable truths about America’s endless wars for power and oil, one important figure stands apart as an inspiration to the whistleblowers of today: Daniel Ellsberg, the whistleblower who leaked the “Pentagon Papers,” over 7,000 pages of top secret documents, in 1971.

A military veteran, Ellsberg began his career as a strategic analyst for the RAND Corporation, a massive U.S.-backed nonprofit, and worked directly for the government helping to craft policies around the potential use of nuclear weapons. In in the 1960s, he faced a crisis of conscience while working for the Department of Defense as an assistant to Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs John T. McNaughton, where his primary duty was to find a pretext to escalate the war in Vietnam.

Inspired by the example of anti-war activists and great thinkers like Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr., he realized he was willing to risk arrest in order to prevent more war. Lacking the technology of today’s whistleblowers, who can carry gigabytes of data in their pockets, he painstakingly photocopied some 7,000 pages of top secret documents which became the “Pentagon Papers,” first excerpted by The New York Times in June 1971.

Ellsberg’s leaks exposed the corruption behind the war in Vietnam and had widespread ramifications for American foreign policy. Henry Kissinger, secretary of state at the time, famously referred to Ellsberg as “the most dangerous man in America.”

Ellsberg remains a sought-after expert on military and world affairs, and an outspoken supporter of whistleblowers from Edward Snowden to Chelsea Manning. In 2011, he told the Chelsea Manning Support Network that Manning was a “hero,” and added:

“I wish I could say that our government has improved its treatment of whistleblowers in the 40 years since the Pentagon Papers. Instead we’re seeing an unprecedented campaign to crack down on public servants who reveal information that Congress and American citizens have a need to know.”