NEW YORK — Few observers were surprised by Donald Trump’s weak performance in last week’s presidential election.

The Republican candidate’s 60.5 million popular votes put him on a par with his predecessors, Mitt Romney and John McCain, neither of whom came close to beating President Barack Obama in 2012 or 2008.

But even fewer expected the massive loss of Democratic votes that cost the party’s nominee, Hillary Clinton, the race.

For all the talk of a “Trump surge,” the only noticeable surge on Nov. 8 was of Democratic voters avoiding the polls.

Clinton’s 61.3 million votes marked a decline of 1.3 million since 2012, and a staggering 5.5 million since 2008.

“No one expected her to lose three states, Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania, that no Democrat has lost since the 1980s,” Peter Feld, a longtime Democratic consultant in New York, told MintPress News.

“If you ask why that happened, it’s most likely because of that collapse of the Obama vote.”

The shocking hemorrhage of Democratic support caught observers across the political spectrum by surprise.

“I had no idea that the Democratic party was so thoroughly alienating its own voters,” conservative attorney and commentator David French wrote.

Leftist journalist Arun Gupta, who had similarly predicted a Clinton victory, wrote: “There’s no getting around the fact that much of the Democratic base repudiated Clinton.”

‘Deeply humiliated’

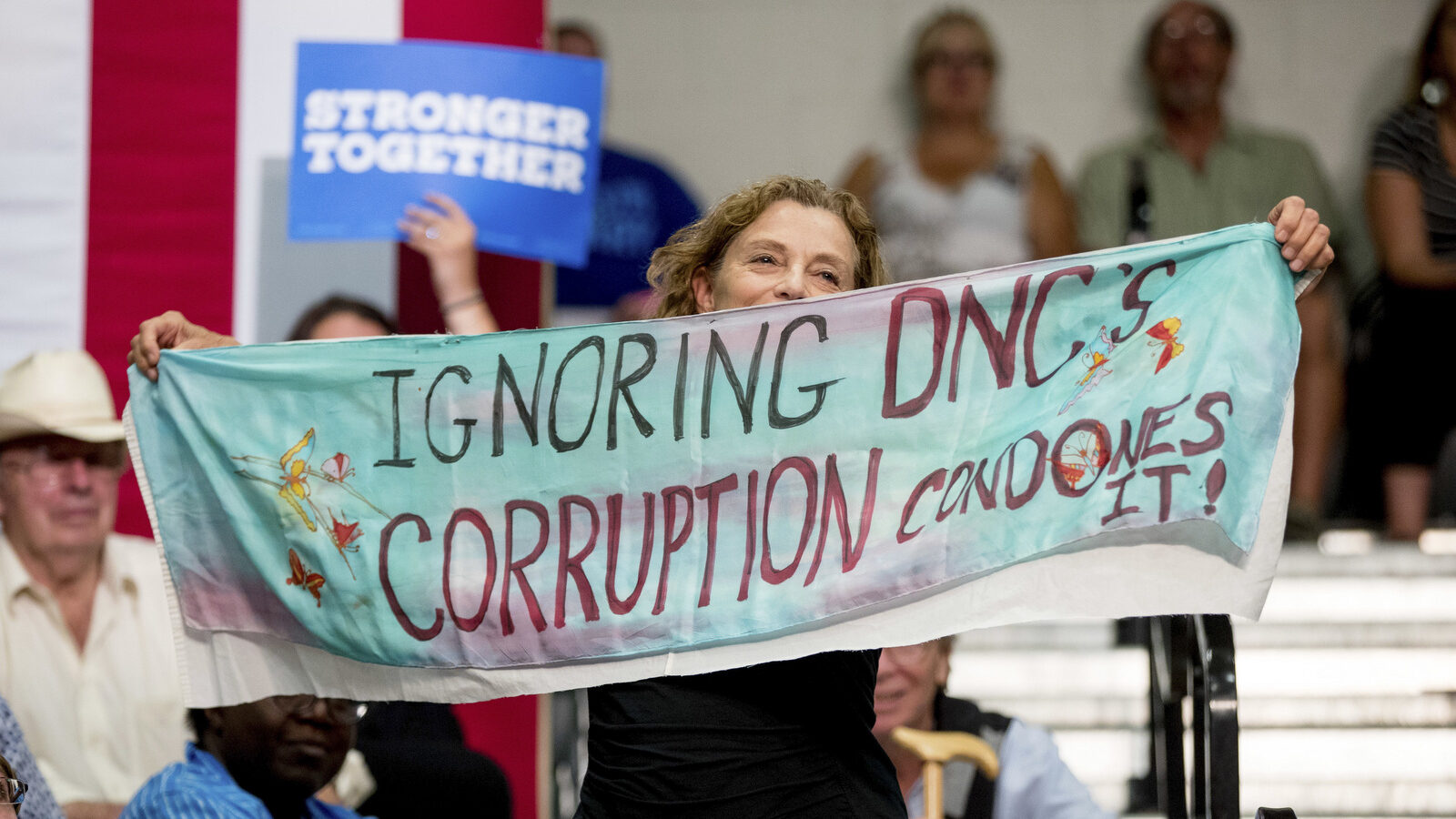

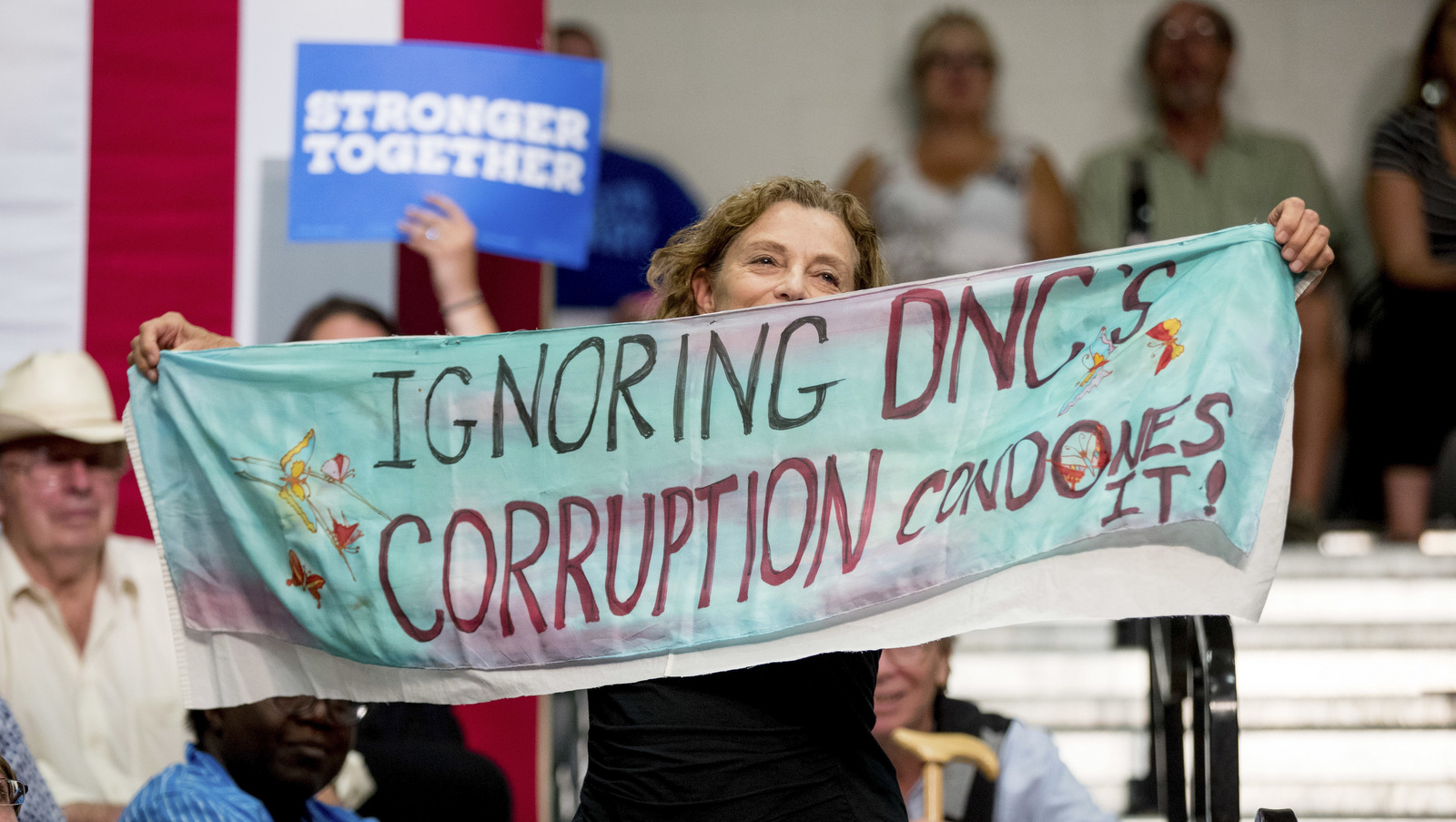

The unexpected implosion of Clinton’s Democratic support sparked dissent at the highest levels of the party, including chaos at the first post-election staff meeting of the Democratic National Committee and demands for the resignation of its interim chair, Donna Brazile.

Many fault the DNC for undercutting the primary campaign of Sen. Bernie Sanders, shown in polls to perform better against Trump than Clinton.

Prior to Sanders’ concession at the Democratic National Convention, he and his supporters argued that he had a better chance of winning the presidency.

Although Sanders has demurred since the election when asked if he would have won it, he has sharply criticized the Democrats’ performance.

“There needs to be a profound change in the way the Democratic Party does business,” he said on Monday.

“I come from the white working class and I am deeply humiliated that the Democratic Party can’t talk to the people where I came from.”

And although Clinton’s initial popularity may have done her no favors, she did little after securing the nomination to improve her own chances.

Largely bypassing key Democratic states like Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, her campaign focused instead on national appeals to defeat Trump, even as the Republican nominee faced mockery for his repeated appearances across the apparently Democratic Rust Belt.

President Barack Obama seemed to criticize the Clinton campaign’s strategy on Monday in his first post-election press conference at the White House.

“Good ideas don’t matter if people don’t hear them,” he said.

“I won Iowa not because the demographics dictated that I would win Iowa. It was because I spent 87 days going to every small town and fair and fish fry and BFW Hall, and there were some counties where I might have lost, but maybe I lost by 20 points instead of 50 points.”

A losing campaign

While the negativity of both campaigns may have inflamed social media, it also depressed voter turnout — an effect that typically boosts the fortunes of Republican candidates.

The Clinton campaign’s talking points included not only Trump’s history of wildly offensive remarks, but also conspiracy theories seeking to tie the candidate to Russia, a country tens of millions of American voters are too young to remember as a threat.

But Clinton’s biggest challenge may have lain in deeply unpopular policies she supported in the past, and particularly their effects on key Democratic voting blocs.

The North American Free Trade Agreement, supported by Clinton and passed during the administration of her husband, Bill Clinton, in 1993 led to the loss of as many as 851,700 jobs, largely unionized positions in the industrial economy.

The ensuing deindustrialization of U.S. cities, accompanied by the near-halving of union density in the private sector, cut deeply into traditional pillars of Democratic voting strength.

Clinton also faced widespread criticism for her support of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, which more than doubled the federal prison population while decimating black and minority communities that have historically mobilized for Democrats.

In short, Clinton confronted the unlikely task of inspiring constituencies devastated by policies she had enthusiastically backed to nevertheless propel her into the Oval Office.

And her trail of disastrous military interventions, coupled with saber-rattling at targets from Iran and Syria to China and Russia, left war-weary Americans with few reasons to trek to the polls.

“The national polls showed her winning the popular vote, and she did,” Feld said, but added: “She didn’t offer a message to turn out those Obama voters who stayed home this time.”

Instead, it seems, Clinton tailored her appeal to a constituency of voters eager for war and austerity, who, it turned out, apparently did not exist and certainly did not vote in sufficient numbers to give her the needed margin of victory.

Democratic disarray

The spectacular collapse of the Democratic Party has left Republicans in control of not only the White House and both chambers of Congress, but also 32 state legislatures and 33 governorships.

Historical trends indicate that Democrats are likely to rebound at the state and congressional levels in 2018, but the party’s own political tendencies may impede its ability to recover from the current era of Republican rule.

Already, some are proposing New York Governor Andrew Cuomo — like Clinton, a darling of the party’s right wing with close ties to the DNC — as a possible presidential contender in 2020.

And Sen. Chuck Schumer, a polarizing figure whose opposition to the Iran nuclear agreement placed him well to Clinton’s right, seems poised to replace Sen. Harry Reid as Senate Minority Leader.

At the grassroots level, many Democratic activists, as well as outside observers, think that continuing the party’s drift to the right will only speed its obsolescence.

“The important task is to break out of the mindset that chases swing voters who will never come around, and instead develop a message and engages people of color and the young — the ones who voted for Obama but stayed home this time,” Feld said.

With the party out of power and without any clear path forward, its future may hinge on the millions of primarily young voters mobilized by Bernie Sanders’ primary campaign, but largely absent from the subsequent general election.

‘Shock, alarm, and fear’

In the meantime, millions outside its confines face the uncertain prospects of Donald Trump’s America and the enigma of a president-elect whose pledges have contradicted each other as often as they have made any sense.

“Trump’s win may be cause for shock, alarm, and fear,” Bernadette Ellorin, chair of BAYAN-USA and an organizing committee member for the U.S. chapter of the International League of People’s Struggle, told MintPress.

Like many other groups across the country, BAYAN-USA, a Filipino-American community organization, has joined thousands in protest in the aftermath of the unexpected election.

Many of these protesters, some taking to the streets for the first time in their lives, plan to join an already-planned protest of the inauguration in Washington, D.C., on Jan. 20.

“In this time of crisis, the biggest risk to social justice movements is to be paralyzed by fear, to not organize, and not unite,” Ellorin said.