In a follow-up of its letter to leaders of the Standing Rock Sioux and Cheyenne River Sioux Tribes, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers issued a statement Sunday clarifying it has no plans to forcibly evict water protectors from camps north of the Cannonball River on December 5.

Issued Friday to Standing Rock Sioux Tribe Chairman Dave Archambault II and Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe Chairman Harold Frazier, the original notice warned anyone presently occupying the Oceti Sakowin and other camps must vacate the land for a designated “free speech zone” south of the Cannonball River, as the area will be closed to the public with no further access allowed.

Sunday’s clarification putatively disputes the widespread assumption the eviction would have to be accomplished by force, stating:

“The Army Corps of Engineers is seeking a peaceful and orderly transition to a safer location, and has no plans for forcible removal. But those who choose to stay do so at their own risk as emergency, fire, medical, and law enforcement response cannot be adequately provided in these areas. Those who remain will be considered unauthorized and may be subject to citation under federal, state, or local laws. This will reduce the risk of harm to people in the encampments caused by the harsh North Dakota winter conditions.

“This transition is also necessary to protect the general public from the dangerous confrontations between demonstrators and law enforcement officials which have occurred near this area.”

Army Corps Omaha District Commander Col. John Henderson claims the supposedly non-forceful eviction is necessary to protect the safety of those presently camped north of the Cannonball River, as well as law enforcement officers:

“Unfortunately, it is apparent that more dangerous groups have joined this protest and are provoking conflict in spite of the public pleas from Tribal leaders. We are working to transition those engaged in peaceful protest from this area and enable law enforcement authorities to address violent or illegal acts as appropriate to protect public safety.”

Henderson did indeed express concern about the violent clashes between water protectors and police in the letter to the Tribes — but said the primary impetus was “due to the harsh North Dakota winter conditions.”

Indeed, he reiterated that point with the new press release, saying, “I am very concerned for the safety and well-being of all citizens at these encampments on Corps-managed federal land, and we want to make sure people are in a safe place for the winter.”

Reuters was unable to obtain further comment from the Army Corps for further explanation of its plans on December 5.

And while the statement it will not employ force appears fairly straightforward — not to mention somewhat mollifying for water protectors fearing a violent eviction — several details prompt imperative questions.

If Henderson’s honest consideration in the choice to close the camps pertained to winter weather, how would a new location just across the river into a designated “free speech zone” — obviously experiencing the same bitter conditions — alleviate worries about the weather?

“We fully support the rights of all Americans to exercise free speech and peacefully assemble,” he continued, “and we ask that they do it in a way that does not also endanger themselves or others, or infringe on others’ rights.”

Exactly whose rights had been infringed, in his mind, wasn’t entirely apparent — at least not in the letter sent to the Tribes’ chairmen. However, in Sunday’s statement, the Army Corps claims land occupied by several camps of water protectors “is currently leased to a local rancher for grazing” — but did not elaborate on whether that rancher had complained.

Additionally, it would seem the Army Corps has taken at face value ‘official’ accounts from the Morton County Sheriff’s Department stating water protectors have acted violently when witnesses in the camps — including journalists and first responders — say police have been responsible for escalating needless force repeatedly. Infiltrators and agitators have also been exposed and told to be peaceful and not act aggressively, or leave the camps.

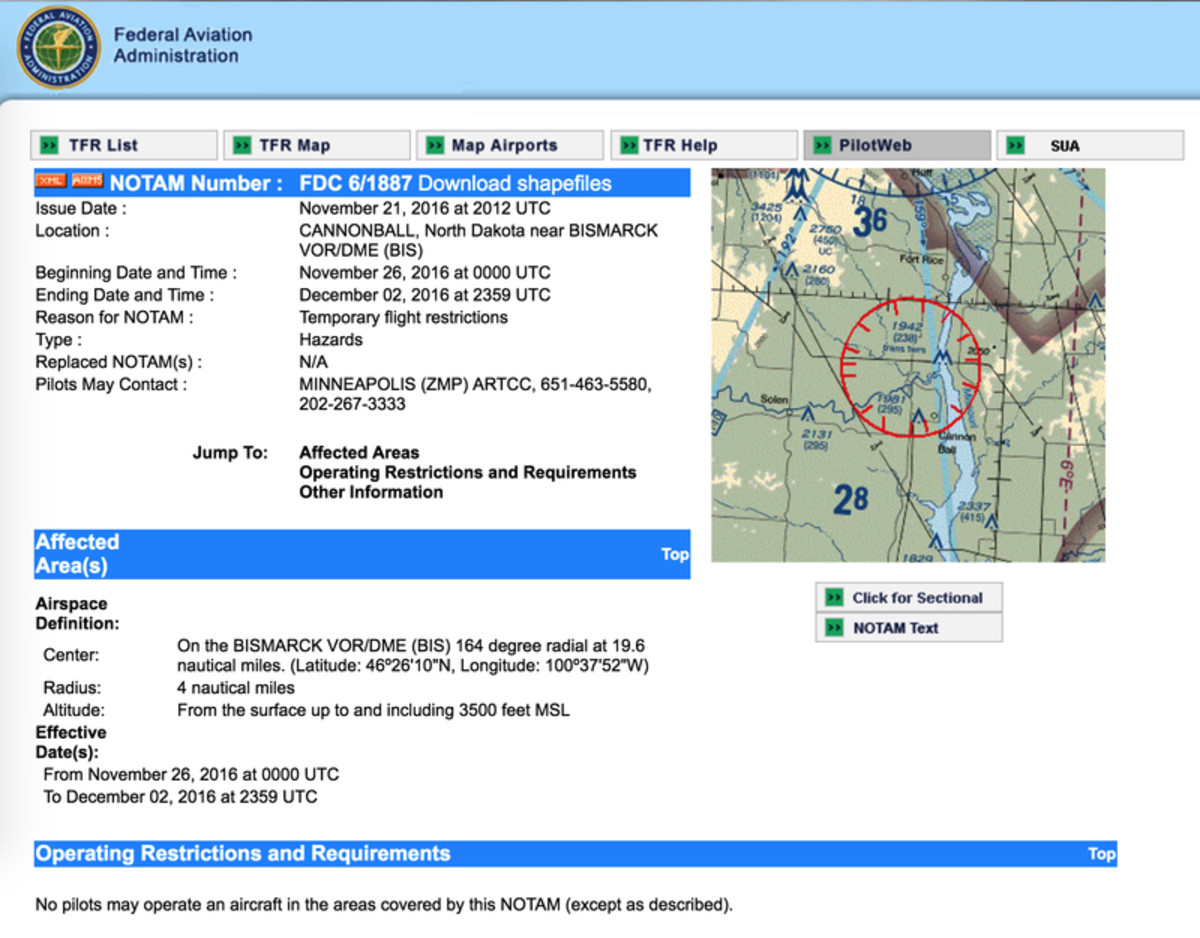

Further, both Archambault and Frazier were shocked by the letter announcing the eviction — and had obviously not been consulted in the matter. However, dates surrounding a no-fly zone — currently in effect over the area — seem to imply the Army Corps’ choice to close the land and evict water protectors had been made days prior to notifying the Tribes.

According to the Federal Aviation Administration, the no-fly zone was issued on November 21, effective beginning November 26 — the day after the Corps informed the Tribes of its plans — and ending on December 2.

The last time a no-fly zone was issued for the area, militarized police forcefully and brutally evicted over 100 people occupying the burgeoning “1851 Treaty Camp” near Backwater Bridge to the side of Highway 1806.

No-fly zones can be issued for any number of reasons, but the parallel circumstances are none the less worth noting.

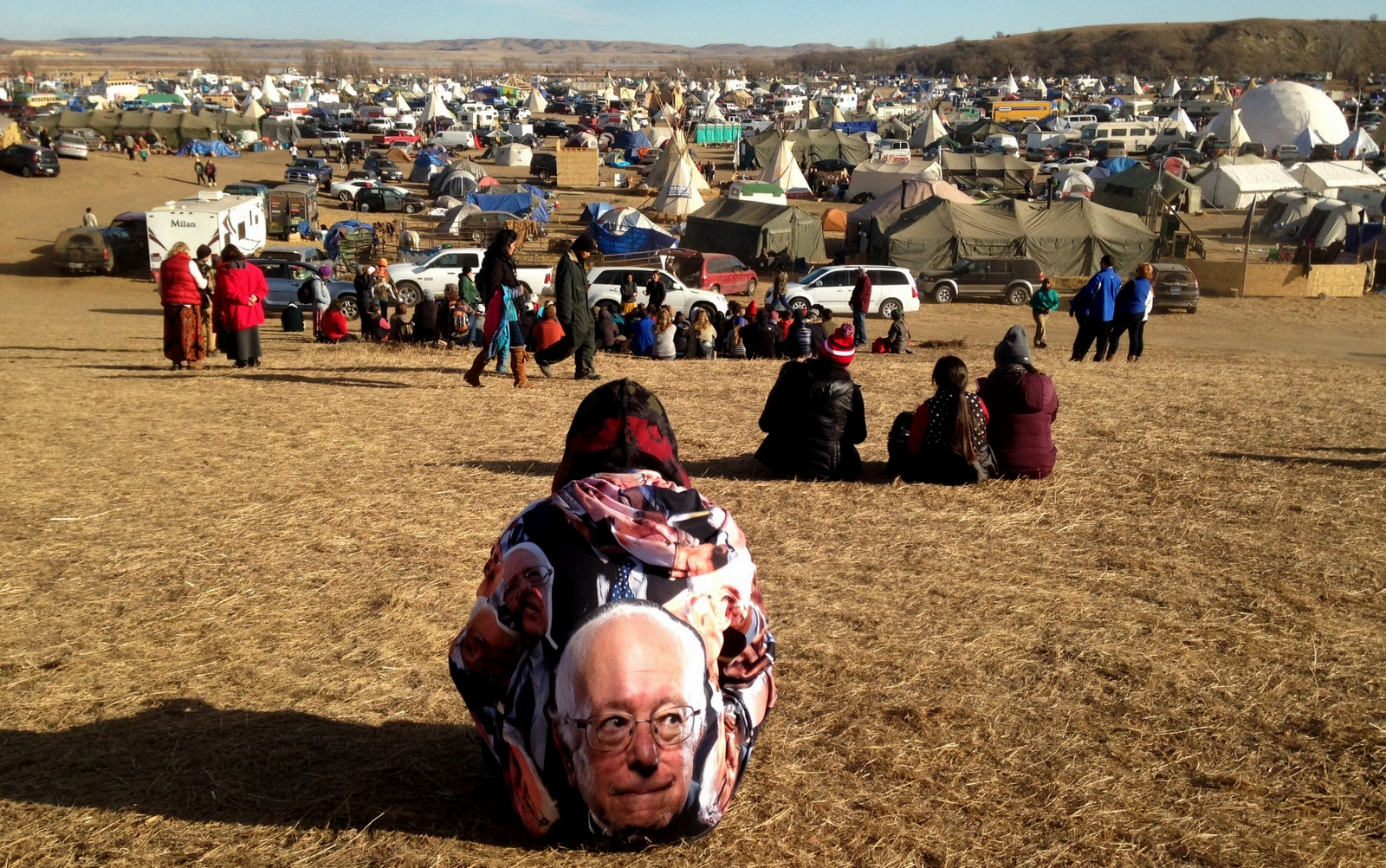

By some conservative estimates, more than 5,000 people — including elders, adolescents, and young children — have settled into the Oceti Sakowin and other camps for the duration of the struggle to halt construction of Dakota Access. While the Army Corps of Engineers states it will not use force to remove these dedicated water protectors, but that they will be subject to citation and loss of emergency responders, seems highly questionable.

All told, nearly every point highlighted by Henderson and the Army Corps stands in direct contradiction to the stated goal of public safety — leaving the looming December 5 deadline no less up in the air than the moment it was first announced.