There’s no doubt about the affection in which Serbia’s Zastava weapons factory is held in the Middle East. Along the wall of Milojko Brzakovic’s managerial boardroom there are tokens of gratitude from the Arab world: plaques from Libya, from the “Public Security Directorate” of Jordan – a smart Hashemite crown above two curved swords – from the Royal Oman Police, even one from “the Palestine Presidential Guard leadership (sic) to Zastava Arms, with great respect and appreciation, 2013”. As for the Syrian war, Brzakovic calls it “a shame to all mankind”.

Nor are the expressions of Arab gratitude mere tokens of esteem. The vast plant behind the boardroom has contracted in its history to produce Kalashnikov rifles, Russian T-72 tanks, the M84 rifle, Hispano-Suiza Spanish anti-aircraft guns and a host of mines and pistols, hand grenades and mountain artillery. In the 19th century – and Brzakovic proudly shows me his state factory’s museum in an old foundry – what was then called the “Technical and Military Works” produced everything from metal church interiors and armored protection for horses to cannons for the Balkan Wars. Indeed you enter this lethal domain in the old Austro-Hungarian city of Kragujevac across the Plaza of the Cannonmakers.

But what interests me are two Zastava instruction manuals I found in the ruined offices of the al-Nusra Front/al-Qaeda groups in newly recaptured eastern Aleppo last year; one for the M02 Coyote machine gun, the other for the 7.62mm M84 machine gun – the first with a blue and white cover, the second coloured green. Not only do they teach users how to strip optical sights and use ‘lock pins’, ‘buffer spikes’ and ‘lugs’, but the 52-page booklet for the M84 includes an analysis of bullet types – “steel core, light… armor piercing incendiary” – tripod assembly mechanisms and lubrication advice.

I push the two manuals across the boardroom table to Brzakovic. He glances at them, nods politely, and pushes them courteously back. He is a tall, moustachioed man, slightly stooped, still a full colonel in the Serbian army – his father was among the first to join Tito’s wartime Partisans in 1941, in the 1st Brigade of Volunteers, which fought right up to the end of the Second World War – and he knows what I am going to ask. How did these documents reach the Islamists in eastern Aleppo? What was for me very tangible proof his ghastly weapons must have found their way to the bloody battle of Aleppo – through legal exports to “friendly” and supposedly law-abiding countries – was for him, I thought, a critical division between public and personal morality.

“What I am sure of,” Brzakovic tells me – and these are words which, in one form or another, I am to hear several times during my travels in Serbia and Bosnia – “is that Zastava Arms and all the [other] producers from the military sector of Serbia do not deliver and export to terrorist organisations or to countries that are under sanctions. And if there are recommendations from the UN or from the EU for some countries where there are conflicts – for example, when the conflict in Ukraine started – no deliveries were sent there.”

Aware the booklets from his factory which I found half buried in the bombed office of a Nusrah/al Qaeda base still lie on the table in front of him, Brzakovic adds “also in Syria, since the conflict started, it [Zastava-produced weapons] is not exported there at all.” But no one has suggested Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Damascus purchased the machine guns whose instruction manuals I found in the former bases of his armed Islamist enemies. What about legal shipments to countries in the Middle East, which might pass on his weapons to al-Nusra, al-Qaeda or Isis?

Brzakovic, a mechanical engineer by trade, looks at me sharply. “We cannot influence nor can we take responsibility if we deliver to the end-user as per contract – as per the EU. We deliver the weapons and we receive confirmation from them [the purchasing countries] that the delivery was received. We cannot take responsibility [for] where their weapons will eventually be used. The responsibility is for the county end-user that [has] taken these weapons. It is their responsibility then.”

He gives an odd example. “How can we control, for example, a delivery to Egypt, as to where these rifles [sic] will eventually be used – we do not have any means to do that. Egypt is only an example. I do not suspect that they do anything. It was just an example.” A very odd example. No one, as far as I know, has ever accused Egypt of sending legally-imported European weapons to Syria.

“Sir,” announces Brzakovic rather pompously, “in the last 15 to 20 years, there is not a single country in the Middle East that did not buy weapons from Zastava – so every country bought them.” It is only now that Brzakovic agrees Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states are among his customers. But how does he account for the Zastava machine gun instructions I found in eastern Aleppo? One of them, for the Coyote, states it is “intended for neutralising and destruction of live forces” and details optical sights, rifle barrel grooves and ranges of up to three miles.

“With each of our weapons we deliver also instructions – the manual for maintenance and handling – but Zastava in Serbia certainly did not deliver the weapons and the firearms to Isis. In battles, Isis has maybe taken these weapons during fighting – it’s possible Isis has captured them from ‘coalition’ forces and this is how they ended up in their possession.”

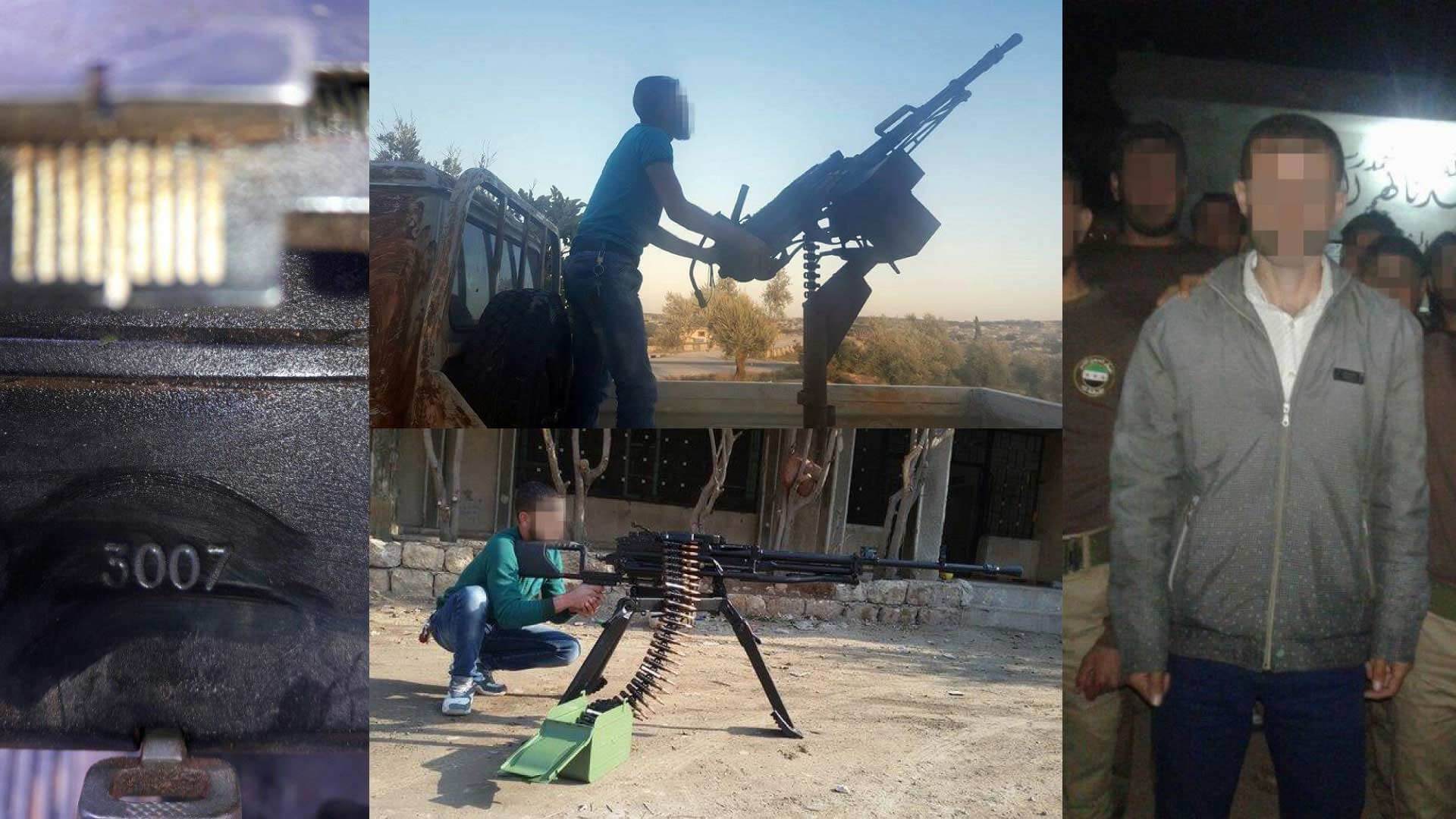

This is a very odd statement. The “coalition” normally refers to Arab armies allied to Nato forces – who certainly don’t fight alongside the Assad government. The Syrian army has Hezbollah, Iranian and other Shia militias fighting on its side but has – as far as we know – no Coyote machine guns in its inventory. But there are photographs of an Islamist fighter in Syria holding a Coyote in February 2016, a year before I discovered the weapon’s manual in Aleppo. And even if Isis or another jihadi group “captured” the weapon in battle, was a fighter likely to have seized the instruction manual – and that of another Zastava machine gun at the same time?

Walking through his factory museum, crowded with anti-aircraft guns, cannons and Kalashnikovs – Mikhail Kalashnikov, the late, greatest Russian arms artificer of them all, visited the Zastava plant several times – Brzakovic takes an almost maudlin attitude towards war.

“What is happening now in Syria,” he says, “is a big stain and shame to all mankind. It’s a shame for the whole of civilization. I personally believe there are high stakes and interests of the big and powerful [involved].” He launches into a speech about the quality of Zastava weapons, but also their minority status among the big weapons producers. “Middle East countries have weapons from more serious countries [than Serbia]: countries like the US, the Russian Federation, western Europe – from Germany, Poland, Britain, France. Compared to the destructive power of the weapons that the big players in the arms industry are delivering to the Middle East, we are just a slingshot. Aleppo was not destroyed by Coyotes and rifles.”

Every weapon produced at Zastava carries an embossed stamp of the company and a serial number, the armorer of Kragujevac says. When “terrorists in Paris were found to have used Zastava rifles” in 2015, he was able to trace each one to weapons originally sent to Yugoslav arms depots before the Bosnian war, and in at least one case to a US arms importer – his account is correct – and he claims every weapon produced in the state factory is listed in archives for the past 40 years. Do I have any serial numbers from Aleppo, he asks, as if I can lug whole machine guns back from the Syrian front lines to Serbia for his inspection.

But Brzakovic is a proud man and there is a lot of George Bernard Shaw’s Andrew Undershaft about him – his armament technical engineering degree, his military school training at state expense – and he remembers a much-admired ballistics teacher telling his class: “Dear children, what we are teaching you today is that in future, one day, you will design and construct this garbage which will take human lives!”

Brzakovic pauses. “I always had this idea that this weapon is used to protect somebody. Since the beginning of my career, I’ve assumed that I am participating in the production of something that will allow people to protect themselves, not to kill people in aggressive wars. But this world, in the meantime, has gone to complete chaos.”

And he then adopts a familiar refrain. Guns do not kill. People kill. “They once killed with spears and then swords and cut off parts of bodies… and when the first gunpowder appeared, they used it for bombs, and unfortunately today we produce intercontinental rockets, we talk about nuclear war. So do you not agree that people kill and that rifles do not?” I suspect Brzakovic is a little vain about his calling, fascinated by the mechanics of weaponry, and I tell him this.

“My late mother,” he replied, “was sitting with me and her other three kids one day and – ‘Micho’ was my nickname – she said to me: ‘Of all of my children, my Micho is the perfectionist.’ And my credo in life has always been: whatever I am doing, either do it perfectly or [do] not do it at all.”

Alas, I fear ‘Micho’ makes as-near-perfect-as-is-possible weapons.

“I wish you to remain healthy,” he adds with fatherly concern. “If you are healthy in life, all the rest you will manage somehow.” Avoiding Zastava bullets will be one of my aims, I assure Brzakovic. “We do not produce any bullets,” he replies sharply.

I’m not sure I would want to repeat all that to the war-shattered people of Syria, not least to its children, who can scarcely be perfectionists at anything. Talking of which, not far from the factory in Kragujevac, the Nazis rounded up hundreds of Serbs for execution in 1941, in revenge for the assassination of German soldiers. When they couldn’t fulfill their quota of hostages, they broke into a local school and seized the children for execution, to make up the numbers.

In all, they shot 2,381 civilians. A small bloodbath, of course, compared to Syria.

Top Photo | In this June 28, 2011 file photo, a visitor looks at assault rifles made by the Serbian company Zastava Arms, during a defense fair, in Belgrade, Serbia. Darko Vojinovic | AP

Robert Fisk is the multi-award winning Middle East correspondent of The Independent, based in Beirut. He has lived in the Arab world for more than 40 years, covering Lebanon, five Israeli invasions, the Iran-Iraq war, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the Algerian civil war, Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait, the Bosnian and Kosovo wars, the American invasion and occupation of Iraq and the 2011 Arab revolutions.

Source | The Independent