A funny thing happened on the way to war with Syria – democracy, that confusingly complex and painfully slow form of government that many, if not most, believe has had the life sucked out of it of late, actually may have stopped a war from occurring. Or at least, British democracy may have.

As it stands presently, the British Parliament stunned the world by narrowly voting down Prime Minister David Cameron’s attempt to have the United Kingdom join with the United States and France in military strikes against the Syrian regime led by President and presumed war criminal Bashar al-Assad. The vote followed a raucous, though cordial debate in the Commons on the wisdom of striking Syria after an alleged chemical weapons attack by pro-Assad forces against civilians just outside Damascus.

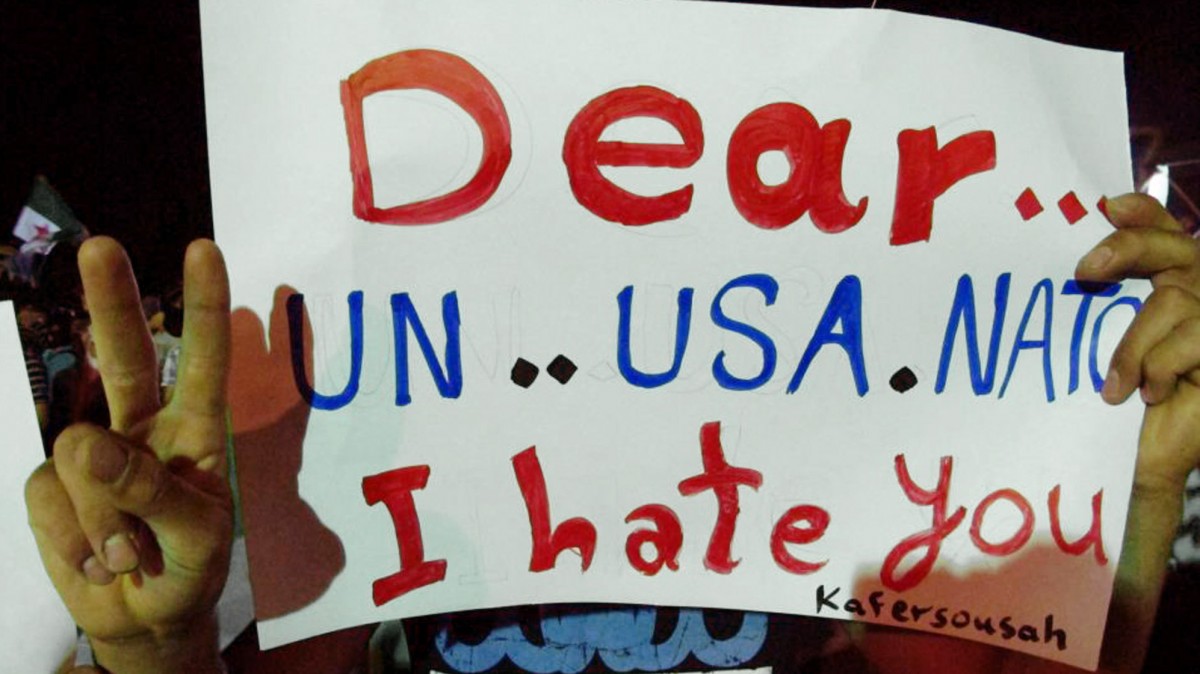

The argument presented by Conservative leader David Cameron apparently did not cut enough of the mustard to sway Parliament, and by a 285 to 272 decision the Prime Minister was forced by parliamentary decision to back down from participating in any US-led strike. This decision in Britain, given the deep public unpopularity of renewed war-making in the Middle East in both the U.S. and Europe, has put renewed pressure on both Washington and Paris to reconsider launching attacks against Assad. Indeed, in the United States only nine percent support taking action in Syria – making a new war against that country less popular than a widely reviled Congress.

More amazingly, the U.S. Congress itself could possibly be gearing itself up to actually do something to prevent war against Syria. House Speaker John Boehner has, for instance, sent a letter to President Obama demanding answers on a wide range of questions pertaining to Syria, including an explanation of how military action, “which is a means, not a policy – will secure U.S. objectives.”

While the Speaker did not also demand President Obama adhere to a formal Congressional vote authorizing military action, such resistance to executive-branch warmongering by an otherwise moribund and hopelessly corrupt legislative branch is refreshing. For his part, President Obama has reacted to Congressional criticism by briefing key members of Congress on the situation in Syria, but so far U.S. lawmakers remain unconvinced. They have urged the President to “do more” in presenting his case for military action.

Could it be, after more than a decade of military adventurism in the Middle East that the West, in particular the United States, is finally tired of wasting its blood and treasure on schemes to bring “order” to that conflict-prone part of the world? Given the certainty with which all thought Western military action was foreordained after reports and video footage of the chemical attack got out, this hemming and hawing by skittish lawmakers on both sides of the Atlantic is almost enough to revive one’s diminishing faith in the democratic process.

Almost

Almost is the operative phrase here, because while Congress is at present showing something of backbone in resisting a rush to war against Syria, continued or even successful resistance to President Obama’s proposed bombing campaign is not assured. Indeed, as we have seen, even deeply unpopular wars have a way of starting and continuing, and insofar as an actual invasion seems off the table, the public is likely to accept — even if it does not approve — a limited campaign of cruise-missile strikes and aerial bombardment.

So, despite the backlash against another ill-advised military adventure in the Middle East, opponents of such action are not out of the woods yet. A bombing campaign may still occur for a number of reasons that, though all bad, are still likely to sway establishment Washington into believing action is warranted despite the abovementioned deep unpopularity of embarking upon such a course.

Remember how Libya’s Qaddafi died?

The first of these is the need to assure U.S. “credibility” in the region – a will-o’-the-wisp concept that refers to the willingness of Washington to back up its demands and statements with military force. Credibility, goes the argument, serves a deterrent purpose by creating the belief in the minds of evildoers like Assad that there are consequences to their actions. Bad behavior – such as allegedly raining down chemical weapons on civilians – will thus seem too costly in face of U.S. military retaliation and therefore prohibitive.

While logical in theory, the idea often fails in practice. In fact, scholars of international politics who have examined this very hypothesis have found it usually does not work. It turns out it is not the “shadow of the future” that compels political actors to decide on war, but the stakes they believe to be at stake in a current, ongoing crisis. By this measure, the relative stakes of Washington and Damascus are absurdly lopsided, suggesting that no matter what America does the regime led by Bashar al-Assad will soldier on in its bad behavior.

This is because Assad, by all accounts, is fighting for his survival. If he and his government go down then he, his entire family, and likely his entire ethnic group will be turned out of power, executed and ground to dust by whoever takes over from them. Compared to sharing the fate of Saddam Hussein – who was hanged – and Muammar Qaddafi – who was drug through the streets and stabbed in the ass by an enraged mob – fighting to the death seems cheap in comparison. Fighting, at least, holds some small hope of survival.

Compared to this, bombing to ensure “credibility” seems small change indeed, and Assad likely calculates that he can survive any ensuing aerial campaign and emerge victorious on the opposite end of it – especially if, as seems likely, the Obama administration is only considering a limited series of strikes that will last only a few days. Many leaders have faced such bombing and survived at the other end it, and so Assad may likely believe that he, too, will survive any amount of limited strikes directed against him.

Hazy memories of Kosovo

This in turn raises a serious problem with the second major argument in favor of Western military action against Assad – that it will be limited in nature. As pointed out above, limited strikes against Damascus will accomplish very little in actually deterring Assad from further mass bloodshed if he or his regime believe their survival is at stake.

This means Washington will have to either stand down from its bombing after achieving very little – itself humiliating and conveying weakness and a lack of credibility to U.S. enemies – or face the prospect of ratcheting up its attacks and commitment, perhaps via the deployment, or at least the threat of deployment, of ground troops of some sort.

Given that this is exactly what happened in the 1999 Kosovo campaign, the fact that bombing supporters are using Kosovo as a positive example of what can be accomplished is not reassuring. Yes, Kosovo was eventually liberated and Serbian atrocities against ethnic Albanians in Kosovo stopped, but only at the cost of enraging Russia, which subsequently used Kosovo as justification for attacking Georgia in 2008. Additionally, Western intervention also likely increased the overall level of violence perpetrated against Kosovars, leading to many more deaths than might othwise have been the case.

Finally, the aerial campaign itself was patently unsuccessful in achieving its goals. It ground on for 78 days and only made the Serbs hunker down and wait out the end of the bombing – which in the meantime reduced much of the country’s infrastructure to rubble. It was only when then-President Bill Clinton and British Prime Minister Tony Blair began vaguely talking about ground troops that Milošević eventually gave up the ghost and recalled his troops to their barracks.

After this, Kosovo effectively became independent and free of thuggish Serbs security forces, yes, but Milošević remained in power in Serbia for another year until he was ousted by his own people in September of 2000. Such an outcome seems unlikely in Syria as there is no territory to detach as in the Kosovo example and there is no guarantee that a deposed Assad will necessarily translate into a non-Baathist Syria.

Lose-lose scenario

This opens another problem with intervention. Suppose Assad and his regime is overthrown and the “rebels” take over. What then? Who will actually take over running the country? Who will be responsible for providing security, power, water and all the other aspects of civilized life to a Syrian population just traumatized by civil war and foreign intervention? At present, it seems very likely that some sort of militant Islamist group will take over given such groups are heavily funded by outside powers such as Saudi Arabia and Qatar. Is an Islamist Syria run by militants really any “better” than a Baathist Syria supported by Iran? Given post-conflict chaos in places like Iraq and Libya, this remains to be seen.

Finally, fourth, the idea that attacking Syria will be relatively costless diplomatically is profoundly naïve. Iran, in particular, will not suffer the disappearance of its major regional ally lightly. Already, it has ordered its Hezbollah allies in Lebanon to shore up Assad, and Western intervention may lead Tehran to broaden the conflict to other areas of the region or even outside it. Russia, too, will also not sit idly by and see a major ally go under, and while Russian military action won’t occur – there will be a major price to be paid with Moscow if Assad goes down.

Meanwhile, China is looking on with interest – and could use the fallout from any action against Syria to secure a firmer anti-Western alliance between itself, Russia and Iran if it so desired.

So, in addition to widespread public opposition to a bombing campaign, there are also a number of sound arguments against intervention, most notably that any successful effort to really stop Assad would likely require using enough force to overthrow him. This in turn would be both expensive and dangerous – and bog the U.S. down even further in a region its best interests dictate it should back away from. Chemical weapons and atrocities are horrific, but not necessarily as horrific as what could come from another open-ended intervention in the very heart of the Middle East.