It started with the best of intentions: In an attempt to find productive uses for military surplus that would be otherwise mothballed, sold to other nations or scrapped for parts, the federal government created a program to pass outmoded equipment to state and local law enforcement agencies at little or no cost.

Equipment — such as the Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected vehicle, which the military found to be unfit for service due to the likelihood of rollovers, issues with electric conductivity via its antennas, and the effectiveness of its armor against explosively formed penetrators — would find a second life with police departments, which may be starved for new gear due to budget concessions, and the military would have more room budgetarily for new equipment acquisitions.

The situation in Ferguson, Missouri, however, shows that even the best of intentions can go awry.

Michael Brown, an 18-year-old black high school graduate just days from entering college, was shot by a Ferguson police officer for allegedly failing to clear the street — a shooting that was enough to pop the bubble of racial tension that existed in the community. In the wake of the news that Brown — who was unarmed at the time of the incident — had been killed, the black community took to the streets in what most describe as peaceful protest.

The Ferguson police response to the protestors — full battle dress, armored vehicles, officers approaching protesters with their weapons pointed at unarmed individuals, liberal dosings of tear gas and rubber bullets — reflects a new reality among police departments: Thanks, in part, to equipment and training gifted from the Department of Defense, many local and state law enforcement authorities have become, in effect, militarized.

All of this begs questions about the motivations behind all of the Department of Defense’s “goodwill.” Who, exactly, benefits? What is really at stake with these gifts to law enforcement?

The police today

Despite the fact that Ferguson is a small town with a population of just 21,000, the St. Louis suburb has grown to become the symbol for racial disenfranchisement in the United States. And even though the town is overwhelmingly black, almost all of the town’s services are predominantly white. This includes the police department — which the mayor disclosed had just three black officers in a force of 57. The ninth-most racially segregated metro area in the country, Ferguson — like the rest of St. Louis — is the product of aggressive racial housing policies, unchecked police targeting and decades of simmering hostilities.

Statistical analysis of the racial situation in Ferguson showed a tense bubble on the verge of bursting prior to the police shooting of Brown. According to ArchCity Defenders, which maintains a court-watching program to track traffic ticket complaints regarding malicious prosecution, 30 of the 60 St. Louis County Courts have been accused of engaging in illegal or harmful practices against black residents.

“Three courts, Bel-Ridge, Florissant, and Ferguson, were chronic offenders and serve as prime examples of how these practices violate fundamental rights of the poor, undermine public confidence in the judicial system, and create inefficiencies,” wrote ArchCity in a recent whitepaper.

ArchCity also pointed out that in Ferguson, which is 67 percent black, 86 percent of all vehicle stops involve a black driver. Black drivers are twice as likely to be searched while stopped, although white drivers are more likely to have contraband. Despite the fact that Ferguson has a poverty rate twice that of the state, court fees and fines represent the second-largest source of revenue for the town.

While certainly unfortunate, the Ferguson police response to the protesters in the wake of Brown’s shooting is reflective of the racial turmoil in the community.

“Nobody is threatening anything,” said CNN anchor John Tapper a little after 11 p.m. EDT Monday on location in Ferguson. “Nobody is doing anything. None of the stores here that I can see are being looted. There is no violence”.

“These are armed police. With machine—not machine guns—semi automatic rifles, with batons, with shields, many of them dressed for combat. Now why they’re doing this, I don’t know. Because there is no threat going on here. None that merits this. There is nothing going on on this street right now that merits this scene out of Bagram. Nothing. So if people wonder why the people of Ferguson, Missouri are so upset, this is part of the reason. What is this? This doesn’t make any sense.”

The response — which included the targeting and arrest of journalists — is proof of the Elaborated Social Identity Model, which suggests that a group of angry people can either be goaded into a riot or defused, depending on how they are treated by police. The impression of the police officer screaming at the crowd with his rifle raised — as has been seen on multiple occasions in Ferguson recently — is as much responsible for the rioting as the protestors themselves, according to ESIM. It is also, in part, a reflection of the notion that “if the only tool you have is a hammer, you treat everything as a nail.”

“The police’s hammer”

“The program that allows local law enforcement or public safety agencies to receive surplus military gear has been around for many years, but since 9/11 it has been on steroids,” said Frank Scafidi, director of public affairs for the National Insurance Crime Bureau, to MintPress News. “The ‘militarization’ of police departments is more the increased awareness among the population and the media that the surplused machines of war have found new life in domestic public safety organizations. If you go back and look at video of other major events, you’re likely to see all manner of former military vehicles providing some level of support to those events.”

“On the other hand, the government has done a pretty good job since 9/11 of beating into our heads all of the nasty things that could befall us at any moment — from a terrorist threat. Cops like nothing more than grabbing onto some cool new (to them, at least) piece of hardware — especially when it was obtained at no cost. But then what? If the gear is in the inventory and an occasion to use it develops, you can bet that it will be used. And why not?”

In recent years, the prestige of getting a piece of military armor has led many communities that have no real need for the military equipment to make requests for them. An example of this is Keene, New Hampshire, which has a population of 23,000 and had only two murders in the last 15 years. Despite this, the town was awarded a grant from the Department of Homeland Security for an 8-ton armored personnel vehicle, the BearCat. The town cited on its application its annual Pumpkin Festival as a “possible target” for terrorists.

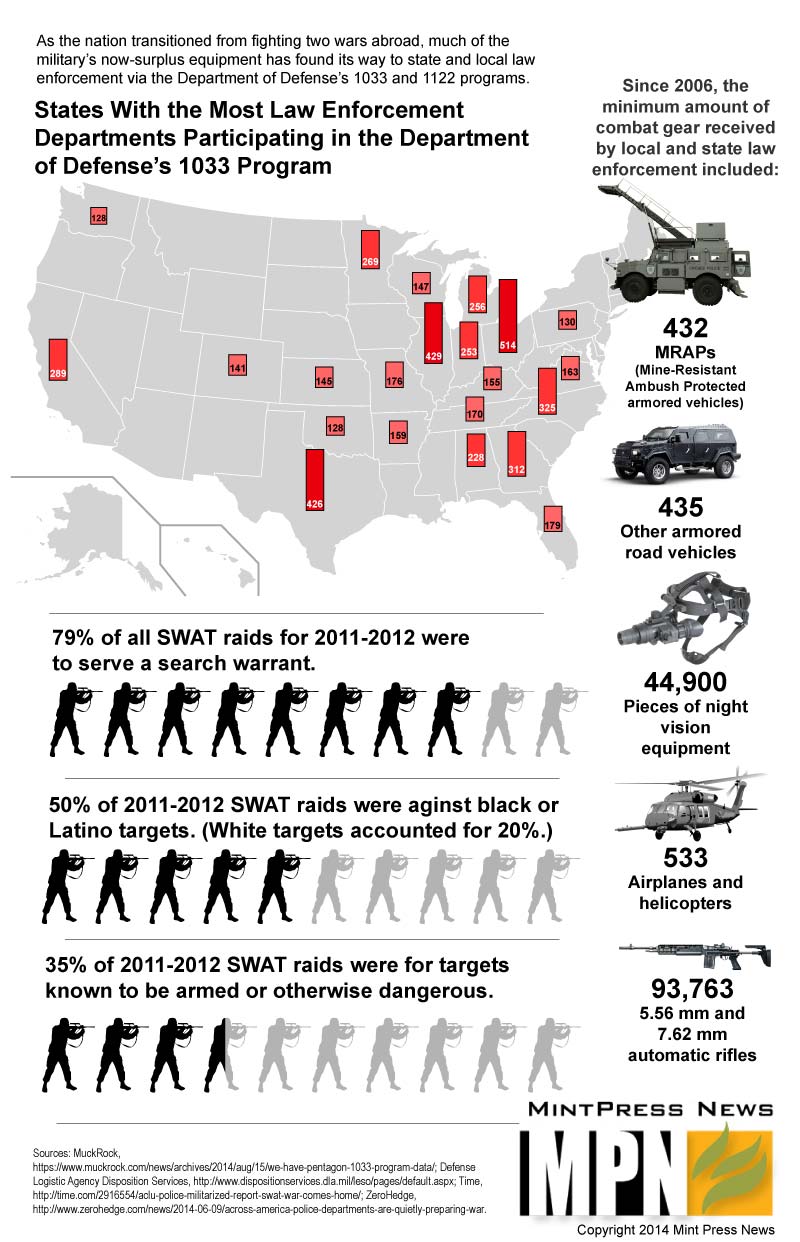

The BearCat made its way to Keene via the United States’ Defense Logistic Agency’s 1033 Program. Operating since 1990, the program is the nation’s primary reverse logistics authority, charged with the disposal of $28 billion in excess materiel per year. The 1033 Program, via the Law Enforcement Support Office, makes available key pieces of equipment that have been labelled to be destroyed or otherwise retired from active use. According to LESO, approximately 8,000 state and local law enforcement agencies participate in the program, receiving in total $5.1 billion in hardware since 1997.

The program was enacted by the 1990 National Defense Authorization Act, which — in section 1208 — authorized the secretary of defense to “transfer to Federal and State agencies personal property of the Department of Defense, including small arms and ammunition, that the Secretary determines is — (A) suitable for use by such agencies in counter-drug activities; and (B) excess to the needs of the Department of Defense.” The idea was simple: Equip police like warriors and they will act like warriors in regards to the “war on drugs.”

Police as warriors

The effect of having police officers act like warriors is immediately noticeable. In one example documented by The New Yorker, Angie Wong and her boyfriend were attending an event at the Contemporary Art Institute of Detroit in May 2008, when 40 Detroit police officers in full battle dress raided the gallery, ordered the attendees to line up on their knees and collected their car keys and confiscated their vehicles. The officers acted on the grounds that the gallery did not have the proper permits for dancing and drinking. Wong witnessed her boyfriend being kicked in the face by one of the officers.

In 1972, the nation saw only a few hundred SWAT-run drug raids per year. In 2013, the number had jumped to approximately 80,000 per year, by one count — this, despite a general decrease in crime over the same timespan.

Many argue that 1033 and other federal-local law enforcement support partnerships are to blame for this increase in law enforcement aggressiveness.

“In the early 2000s I was an elected commissioner in my then-home town in Maryland, population about 1,110 residents, with a police force of a half-dozen,” said Edward Hudgins, director of advocacy at The Atlas Society, to MintPress. “I served a few years as police commissioner. After the 9/11 attacks we found that even small jurisdictions like ours could get extra funds in the name of national security — a major road and possible evacuation route out of D.C. passes our town, so there was a legitimate security concern. We chose communications and other such equipment.”

“But it has been shocking how police forces across the county are now equipped more like military units than traditional guardians of the peace. This trend poses a clear and present danger to liberty in America.”

In response to the notion that the situation in Ferguson was fueled by easily available, non-essential military gear, President Obama took a diplomatic road when addressing the issue.

“After 9/11, I think, understandably, a lot of folks saw local communities that were ill equipped for a potential catastrophic terrorist attack,” the president said on Monday. “And I think people in Congress, people of goodwill, decided we’ve got to make sure they get proper equipment to deal with threats that historically wouldn’t arise in local communities.”

“I think it’s probably useful for us to review how the funding has gone, how local law enforcement has used grant dollars, to make sure that what they are purchasing is stuff they actually need,” he continued. “Because there’s a big difference between our military and local law enforcement and we don’t want those lines blurred.”

Understanding the pipeline

Despite the president’s goodwill toward Congress, they may not be deserving of such praise. In June of this year, the House voted overwhelmingly to block legislation from Florida Rep. Alan Grayson that would have ended the 1033 Program. The vote was 62-355, with every Republican and one-third of the Democrats voting against it.

To put this vote into perspective, a deeper breakdown of how the House voted is needed. According to MapLight, representatives who voted to continue funding of the 1033 Program received, on average, 73 percent more defense industry contributions than those who voted to defund the program. Of the 59 representatives who received more than $100,000 from the defense industry from Jan.1, 2011 to Dec. 31, 2013, only four voted to defund 1033.

1033 creates a pipeline between local police departments and military contractors. In practical terms, the program introduces local and state law enforcement agencies to defense contractors, who benefit from the demand for parts, ammunition and servicing for the new equipment acquired via 1033. Through this introduction, the law enforcement agencies are likely to buy additional firearms, vehicles and other gear from the manufacturer — either through budget outliers or through funds from asset forfeiture, or the seizing of property and money by law enforcement suspected to play a material role in an alleged crime or offense.

Most poignantly, as reported by the American Civil Liberties Union in its report “War Comes Home: The Excessive Militarization of American Policing,” the Defense Logistics Agency has the capability to direct-buy equipment for local police departments from the defense contractor without the equipment ever becoming a part of the military’s active inventory.

“Similar to the question of why the federal government is allowing drones to fly without clear civil liberties protection, this problem centers around money,” said John Whitehead, president and spokesman of The Rutherford Institute, to MintPress. “They are estimating that Boeing and Northrop Grumman are set to benefit from a $30-billion-a-year industry starting in 2015 with the drones. It may be drones used overseas that will be sold, but there is money to be made.”

“What does a town of 28,000 people with no crime need with a MRAP? Could this all be that the federal government simply wants to get rid of equipment? Maybe; maybe the DLA are good souls that just want to see the police have MRAPs. But, I am cynical. I feel that it is dangerous for the police to have this equipment. Why, exactly, is it necessary for a police officer to sit on top of a MRAP in camouflage clothing when just talking to the protestors would have put down this whole mess.”