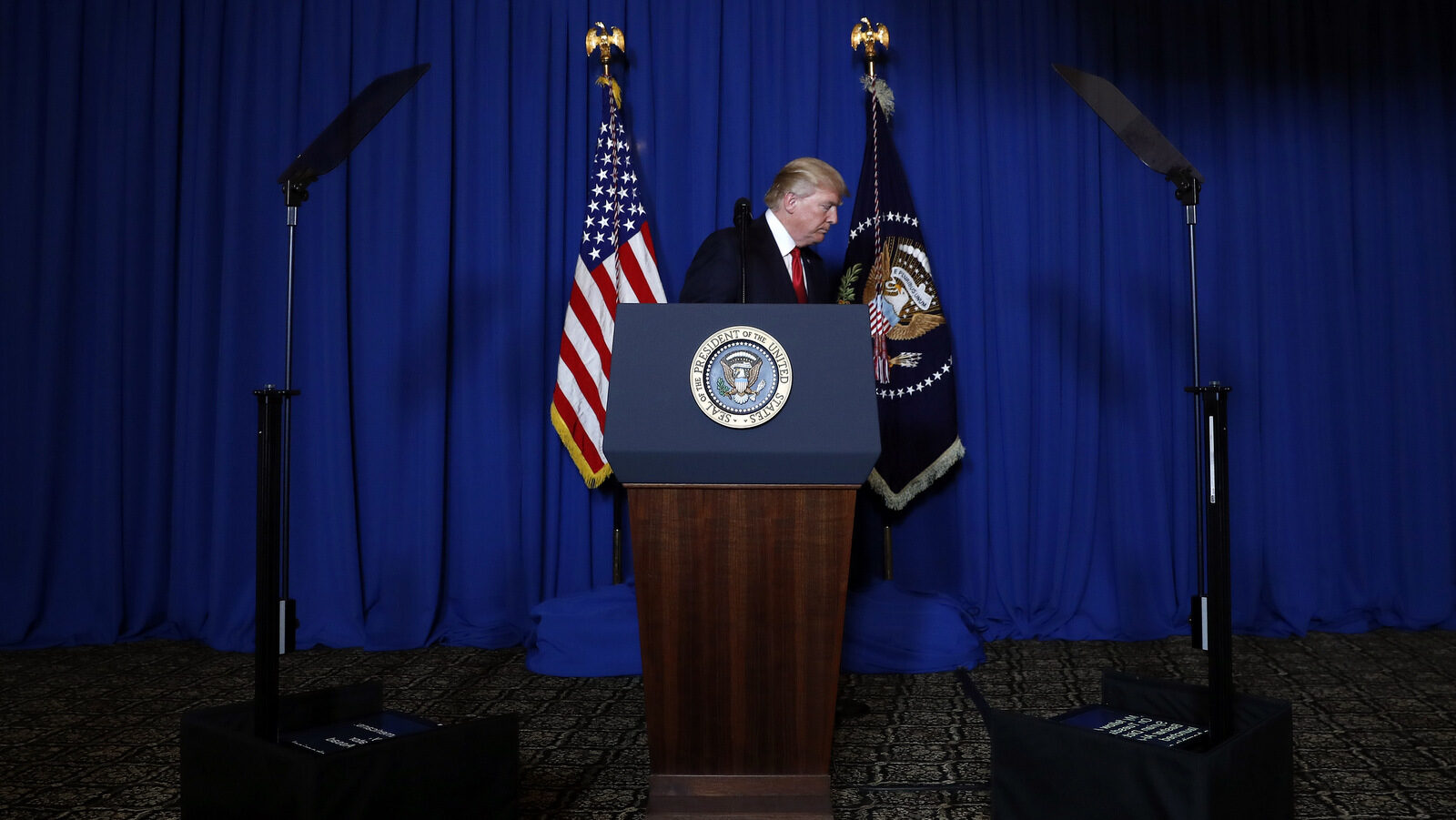

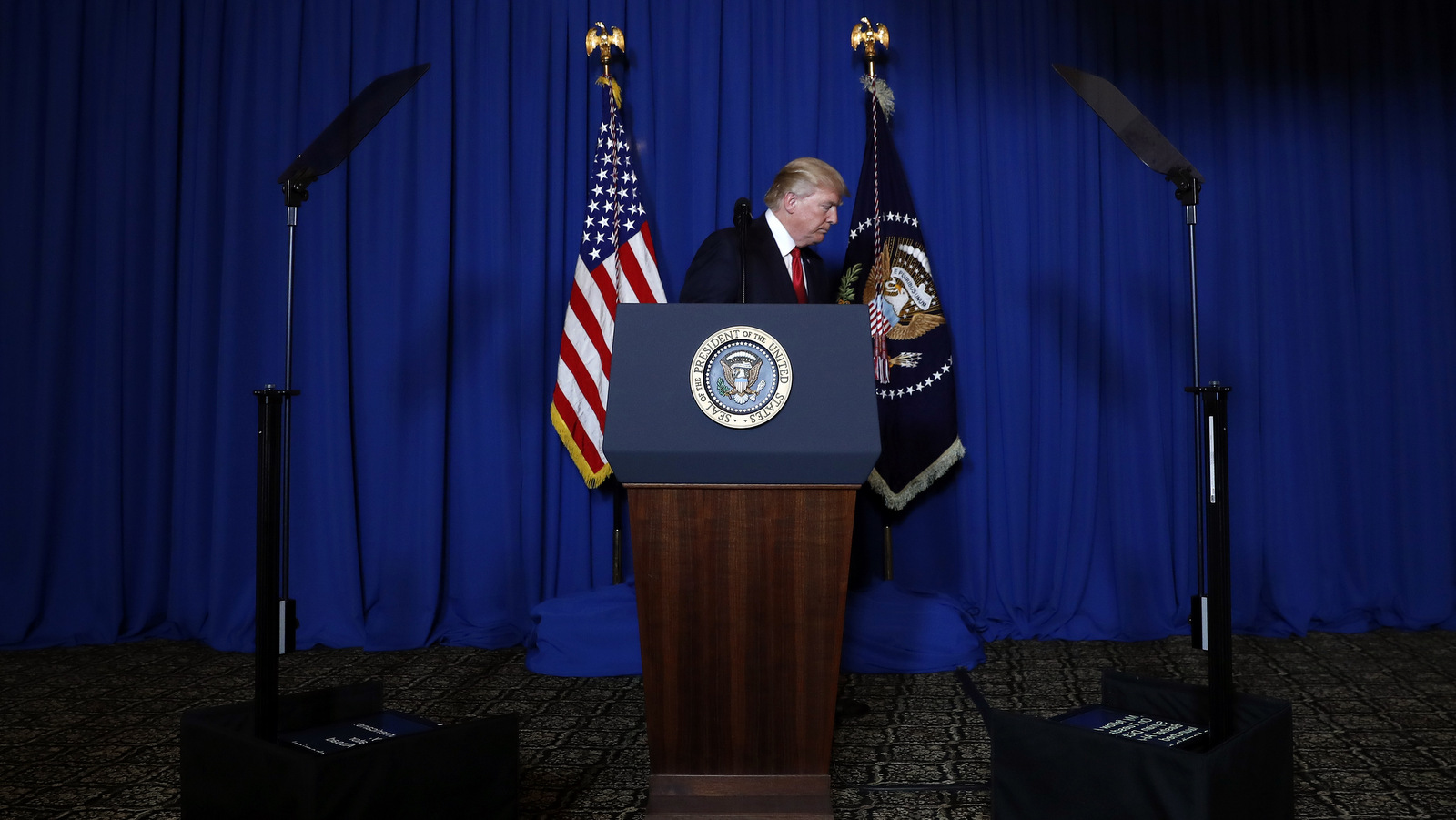

The US has called its attack on an airbase in Syria “a strong signal” for the Assad regime. Legal experts, however, criticized the action. In an interview with DW, international law expert Stefan Talmon explains why.

DW: Under international law, what are the conditions for a military attack?

Stefan Talmon: An airstrike, like any other attack on a state, requires a mandate from the UN Security Council. According to the UN Charter, all five great international powers, must, as permanent members, approve of a military attack. Or in exceptional cases – if there is no UN mandate – a case must be made for self-defense.

When can a UN Security Council authorization be omitted? Are there exceptions?

“Humanitarian intervention” is often discussed in international law. This includes cases in which a state uses violence or inhuman practices against its own population. In this case, one considers whether other states are allowed to intervene to protect the population from its own state and government. This is one of the justifications stated for the NATO air strikes in 1999 against Serbia in the Kosovo conflict. At that time, several states cited humanitarian intervention as a reason. This justification was then rejected by the overwhelming majority of nations so that today, we can actually say that unilateral humanitarian intervention without UN Security Council authorization is not provided for in international law. The same is valid for the so-called institution of the responsibility to protect.

The Kosovo intervention at that time violated international law but some states tried to change international law by displaying different behavior and waiting to see how other states would react. That is how customary international law develops. A state deviates from the existing legal rules through its actions but indicates that it would like to establish new official rules. Then it must wait for the reaction of other states.

Would this type of procedure excuse the US action in Syria?

At the moment, they are not covered by international law. If the US requested a change in law, it would have to proactively represent its interests. It would have to present this legal position to other states for discussion. The American side has not yet done this.

Has the strike on Syria sparked discussion on changes to international law?

There are always discussions in the field of international law but the majority of my colleagues who have thus far viewed the attack on Syria as a violation of international law.

Could any sort of action on the part of the US “remedy” this?

No, a retroactive remedy is not provided for in international law, and in this case, it is highly improbable that the UN Security Council would retroactively authorize this action.

Does international law recognize the possibility of acting for “moral reasons?”

International law is quite value-free in that way. There are positive rules that were made after the Second World War on when violence is lawful and when not. These rules have created a tight framework. The use of force was fundamentally centralized at the United Nations. It prevents strong individual states from taking the law into their own hands. The five great world powers, as permanent members of the Security Council, are expected to unanimously agree to military action and be held accountable for its consequences.

If the US did not act in accordance with international law, from whom could it expect sanctions?

Syria could theoretically bring forth the case of use of force by the US to the UN Security Council. But since the US is one of the permanent members of the UN Security Council, the Security Council would probably not reach a decision with regard to the use of force, especially because there would be no condemnation from the US.

What does it mean when the German government says it finds the attacks “understandable?”

It means that the attack is morally understandable. Emotionally, it is certainly understandable. Something wrong happens and you want to do something about it. But the law has clear rules and it first requires clear evidence for attacks. In the case of Syria, international law requires an international investigation. The United States and Syria both signed the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) of 1993. It outlines what must be done in the case of chemical weapons deployment. An international investigation must be conducted. The results must be reported to the conference of the signatories. This conference can then recommend measures, but only non-violent ones. And if it considers collective violent measures to be necessary, then it must abide by the UN Security Council. Those are the rules.

Germany’s defense minister, Ursula von der Leyen, is of the opinion that there is already a resolution by the Security Council that would allow the states to take violent action against Syria if chemical weapons were deployed. Is that correct?

It is wrong. There is a resolution, Resolution 2118 from 2013. In it, the UN Security Council decided that if any chemical weapons are deployed in Syria – no matter by whom – it would impose measures under Chapter VII of the UN Charter. However, the UN Security Council would have to become active again. In Resolution 2118 itself, no measures – including military action – have been outlined. That is why this resolution cannot be used as a basis for the US’ unilateral action.

Perhaps you recall the Iraq war in 2003. There, several states tried to justify use of force against Iraq by using previously existing UN Security Council Resolutions from 1990 and 1991. The US tried to interpret these decisions as permanent permission for the use of force. The majority of international law experts rejected this line of argument. The rules that were put together after 1945 are justified. Unilateral measures always bear the threat of an escalation of violence, even a world war. That is why the UN Charter security mechanisms have been integrated.