This year marks the final season of the acclaimed AMC series “Breaking Bad,” which portrays a struggling high school chemistry teacher with inoperable lung cancer. He subsequently turns to a life of crime, producing and selling methamphetamine with a former student to secure his family’s financial future before he dies.

The program has garnered high ratings and a huge following. What we haven’t heard regarding this program is a widespread condemnation for its glorification of the violence and the illegal drug trade. This can’t be said about Black artists who may approach those same topics in their music.

When the popular HBO series “The Sopranos” came to a close, and the show’s stars made the rounds of talk and late-night shows, this writer found America’s obsession with the show perplexing. Then again, why should it be? This was just another example of America’s propensity to embrace the glorification of violence and criminal activity in entertainment when those pulling the triggers and those doing the killing are White.

A&E, which aired “Sopranos” reruns, had a commercial promoting the show that showed a tractor exploding after the driver turns the key, a woman in a convenience store removing a bag of ice from a freezer to reveal the face of a murder victim, and two kids smashing a bicycle with baseball bats. This is accepted, celebrated or simply ignored. And so the decolorization of White violence in entertainment is achieved.

In that same vein, some years ago, AMC ran a promotion for a “Godfather” movie marathon that consisted of scenes from the “Godfather” trilogy with gangsta rap playing in the background. Maybe they were just trying to reach a more contemporary audience, but whether knowingly or unknowingly, AMC made a critical cultural and historical connection – a connection made by far too few people in this country. Many people, White and Black, continue to treat gangsta rap (and Black culture as well) as if it were not informed and shaped by the dominant culture’s values.

Even a great deal of White liberals and progressives seem to believe that Blacks in America hail from a different planet than they do – a planet that hasn’t been touched by this society’s longstanding history of glorifying violence and celebrating gangsterism. Indeed, society appears to believe that only Blacks have influenced Blacks and the diseases that are contracted from the defects in American culture have played no significant role in impairing or impacting the people of color in this nation.

Beginnings

It can be argued that the beginnings of the deracialization of White violence in America began in the colonies when Native Americans were portrayed as savages for acts that Whites were equally guilty of — acts of aggression that would have been deemed self-defense had the “aggressors” not been Native American. Let us focus, however, on the American romanticization of the White outlaw and gangster in popular culture and film.

One of the most powerful examples of this “Whitewashing” of history and criminal activity is found in the legend of Jesse James. The story of Jesse James remains one of America’s most prized myths… and one of its most erroneous.

Jesse James, so the legend goes, was a Western outlaw – even though he never went west; he was an American Robin Hood – yet he was an equal opportunity criminal in that he robbed from the poor as well as the rich, and kept it all for himself.

And as for his reputation as a gunfighter… his victims were almost always unarmed. James, like many of his victims, met his end as an unarmed man shot in the back.

We see his image romanticized time and again through various films (the most popular being the 1939 version starring Tyrone Power) and historical retellings. He is sensitively portrayed as the reluctant outlaw; the Confederate idealist who was pushed into a life of crime. In this description we see the interconnectedness of the media, popular culture and public perception in creating and buttressing America’s time-honored folk tales. This is repeated in the tales of Doc Holliday, Billy the Kid, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and so on.

The American Gangster in early American cinema

Yes, Al Capone, by the end of the 1920s, was the archetypal symbol of American gangsterism, but his popularity and perceived charisma was imitated in many popular gangster films. Other figures such as Bonnie and Clyde, the Barkers and Pretty Boy Floyd have all been sanitized and romanticized as well, giving them Robin Hood-like status in popular culture.

Lee Horsley of Lancaster University explained classic gangster film sociology as thus:

[T]he mythologized gangster can only be understood in relation to the wider society, whether he is cast as a villain whose actions confirm the need for law and order or as an outlaw hero admired for the toughness and energy with which he defies the system—the “outlaw hero” perspective has to also be understood in its racial context as well.

Having made a career of illegality, the gangster functions as the dark double of ‘respectable’ society, undermining its claims to legitimacy and parodying the American drive to succeed; underworld activities image the injustices and vicissitudes of American economic life, with its illusions of upward mobility, its preoccupation with image-building and its hierarchy of exploiters and exploited.

Let’s face it, Blacks, who were hounded by even harsher social realities than White ethnics, never were or would be cast as “outlaw heroes” in the early days of film. This dynamic still persists as the double-standard regarding which ethnicity should and shouldn’t be granted “justified outlaw” status.

The Scarface generation

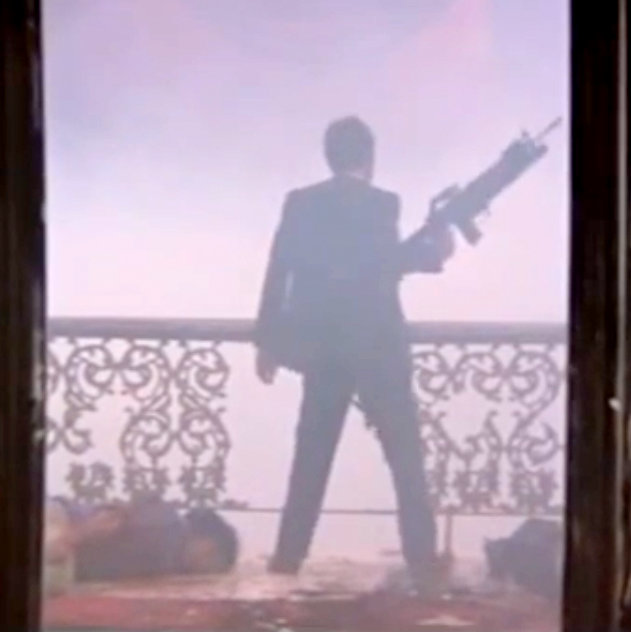

Perhaps no film has made more of an impression on what would later become gangsta rap than the 1983 film “Scarface” — the name Scarface, and its many variations, can be found in scores of songs and albums (as well in artist and group names). It stars Al Pacino as Tony Montana, a Cuban immigrant who shoots and kills his way to the “top” to become the head of a powerful and brutal drug empire. It also, in this writer’s opinion, is far and away one of the most explosive and bloody films in the history of the gangster film genre.

Four short years later, Los Angeles-based rapper Ice-T emerged with his album “Rhyme Pays” (1987) which depicted hardcore street life. In 1988 N.W.A.’s (Niggaz With Attitude) underground album “Straight Outta Compton” firmly established gangsta rap within the American music scene.

Its keynote track “F*** Tha Police” was considered so shocking that radio stations and MTV refused to play it. Nonetheless, the album went platinum. N.W.A. and gangsta rap’s popularity was compounded with the release of their second album “EFIL4ZAGGIN” in 1991, which debuted at number two on the Billboard chart with neither a single nor a video and became the first rap album to reach number one. Snoop Dogg then became the first rapper to go straight to number one with his album “Doggystyle” (1993).

The reliance on crime in the lyrics of gangsta rap fuels much of the controversy surrounding the musical style. And while it has been criticized for glorifying the negativity of the streets, gangsta rap’s defenders claim that the rappers are simply reporting what really goes on in their neighborhoods.

In other words, they are telling a story through their specific cultural and experiential lens. The genre must be properly contextualized.

Conclusion

Granted, the high-profile scandals and tragedies that have accompanied some of the biggest names in rap and gangsta rap adds fuel to the charges of it being too violent — such as the trials of Sean “P Diddy” Combs and Snoop Dogg as well as the murders of Tupac Shakur and Notorious B.I.G. Nevertheless, this writer remembers gangsta rap in its infancy (before any of the aforementioned incidents took place) and condemnations of its ultra-violent lyrics and persona were being voiced even then.

The bloody Genovese and Colombo crime family wars were taking place in New York in the early 70s (when the first two “Godfather” movies were released) and a correlation between that reality and “The Godfather” was never made. Neither was any strong assertion made concerning Brian DePalma’s “Scarface” glorifying and promoting the very real cocaine-financed mafia that was on the rise in the 80s.

The dominant culture enthusiastically amen-ed any supposed gang-affiliation of some gangsta rappers, but either glorified or winked at Frank Sinatra’s oft-reported mob connections (some even believe those connections helped to deliver JFK to the White House).

In American popular culture and in the consciousness of the American public, White violence and crime is deracialized. Black problems and concerns are usually treated as some sort of racialized pathology, whereas White indiscretions and transgressions are viewed as the innocuous and colorless “societal” or “social” ill — detached and divorced from Whiteness. (As recently as 2007, Salon.com even titled a piece about Tony Soprano, “Our Favorite Murderer.”)

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not a prude. Although, I am by principle against a great deal (if not most) of the violent messages that are transmitted through some films and music, that does not prevent me from gleaning powerful ideas, concepts and perspectives from those same films and forms of music (“The Godfather,” N.W.A, “Scarface,” included).

The sexism and carnage in “The Godfather” that I am opposed to does not blind me to the depth of the characters and the complexity of the storyline. Likewise, gangsta rap’s misogyny and violence that I abhor – this writer cannot embrace anything or anyone in the current scene — does not negate the fact that those artists did bring to the forefront many issues and concerns of the Black community — such as racial profiling, poverty, gang life and police brutality.

I suppose the point here is that if the concern is violence in entertainment, then make the condemnation of it across the racial and ethnic board — no matter how sympathetic, charismatic, heroic or complex as they make the Walter Whites, Michael and Vito Corleones, the Tony Montanas or the Tony Sopranos.

Because if the eradication of violence in entertainment begins and ends with Black faces and Black voices, then it’s a strategy that is bound to fail. Or if one believes that proper perspective and context must be used in critiquing these popular mafia films and series, that’s fine.Just don’t fail to apply that same drive for context and perspective when judging the music and messages that flow from a Black outlook. And finally, don’t divorce that critique from the long history of White ethnic violence in American cinema and popular culture that preceded and even helped to influence that same Black outlook.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Mint Press News editorial policy.