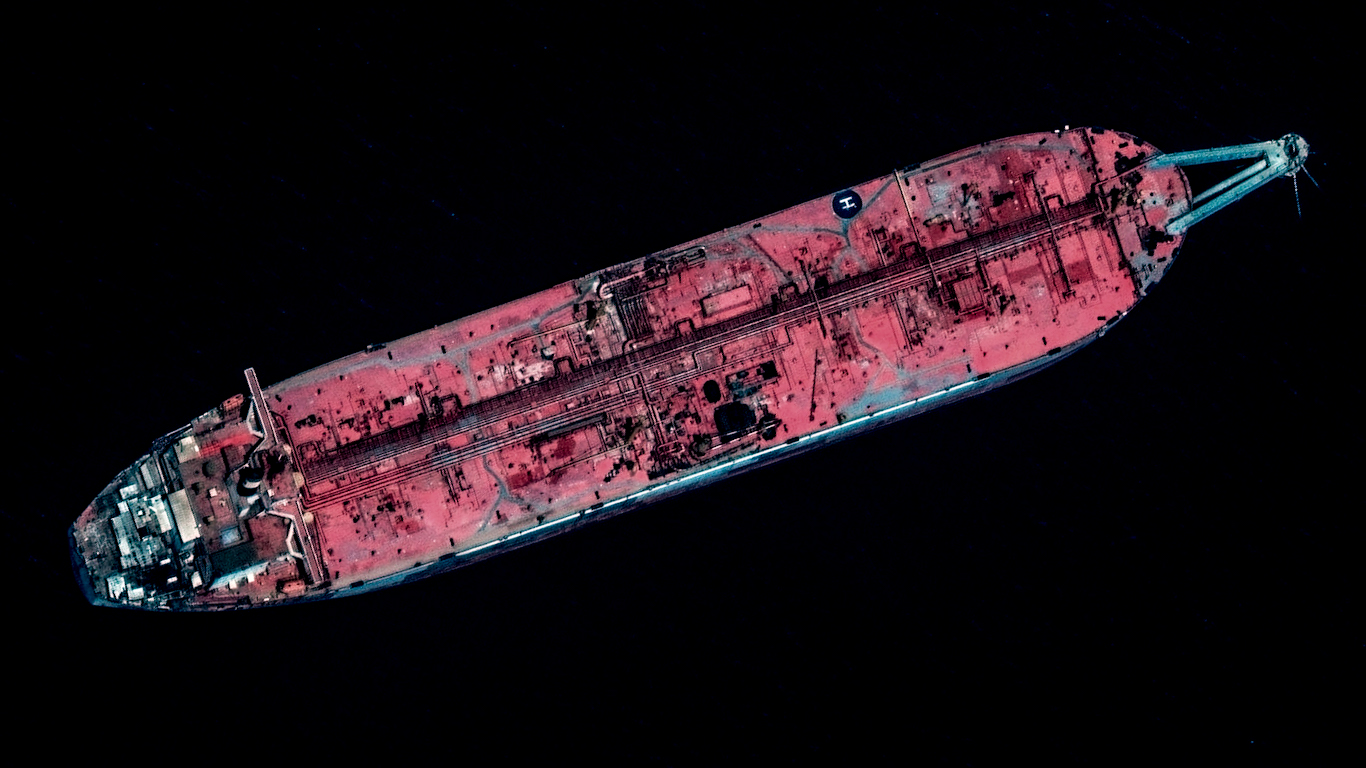

HODEIDA, YEMEN — In the wake of the deadly port explosion in Beirut, Lebanon on August 4, many in Yemen are hoping that the world, and the United States and Saudi-led Coalition, in particular, will have gained a renewed sense of urgency in working to avoid a similar disaster off the coast of Yemen in the heavily traveled Bab al-Mandab Strait, one of the worlds’ busiest international shipping lanes. There, the FSO Safer sits roughly 25 miles northwest of Yemen’s port city of Hodeida, not only threatening the poorest country in the Middle East but also posing a very real threat to all countries bordering the Red Sea and to international navigation in general.

The vessel, which is filled with an estimated 1.1 million barrels of crude oil, has already entered a critical stage and is vulnerable to a disaster that could potentially rival that seen in Beirut. With its built-in weight of 409,000 metric tons and a capacity of more than a million barrels of oil, the FSO Safer contains enough volatile material, over 150,000 metric tons of oil, to make the reported 2,750 metric tons of ammonium nitrate housed at the Beirut port seem relatively insignificant. Though crude is not typically as explosive as ammonium nitrate, in the right conditions, it can be very volatile. In the 2013 Quebec Lac-Mégantic rail disaster, 47 rail cars carrying crude oil caught fire, exploded, and produced a blast radius of one kilometer, leveling much of the town of Lac-Mégantic, killing more than 40 people and creating a massive environmental disaster.

The potential explosion of the Safer could leave millions of people already struggling against starvation, disease, and epidemic amid a Saudi-led bombing campaign and blockade vulnerable by forcing the closure of the Hodeida port, the gateway for 90 percent of the country’s food, medical and aid supplies, and by strangling traffic on one of the world’s busiest waterways, the Bab al-Mandab Strait.

Dozen of fishermen in Hodeida who spoke to MintPress expressed deep concern. They called the FSO Safer a “floating bomb” lurking off their coast and say it could destroy their last source of food and income. An oil spill in the Bab al-Mandab Strait would affect more than 100 Yemeni islands and coastal provinces, including Hodeida, Hajjah, and Aden. It would also eradicate millions of tons of fish stocks, shattering the lives of Yemeni fishermen already facing impossible odds: bombing, free-falling fish stocks, shattered boats, an unreliable sea, hunger, and disease.

An oil spill in the Red Sea port would also destroy sensitive marine ecosystems and pose a threat to what remains of Yemen’s coastal tourism. Worst of all, officials say, it could leave millions of people in Hodeida without clean drinking water. Experts at IR Consilium, a consultancy firm focusing on maritime law and security, warned that a spill in the area would force multiple desalination plants surrounding the Red Sea to close, depriving millions of access to clean drinking water.

A ticking timebomb

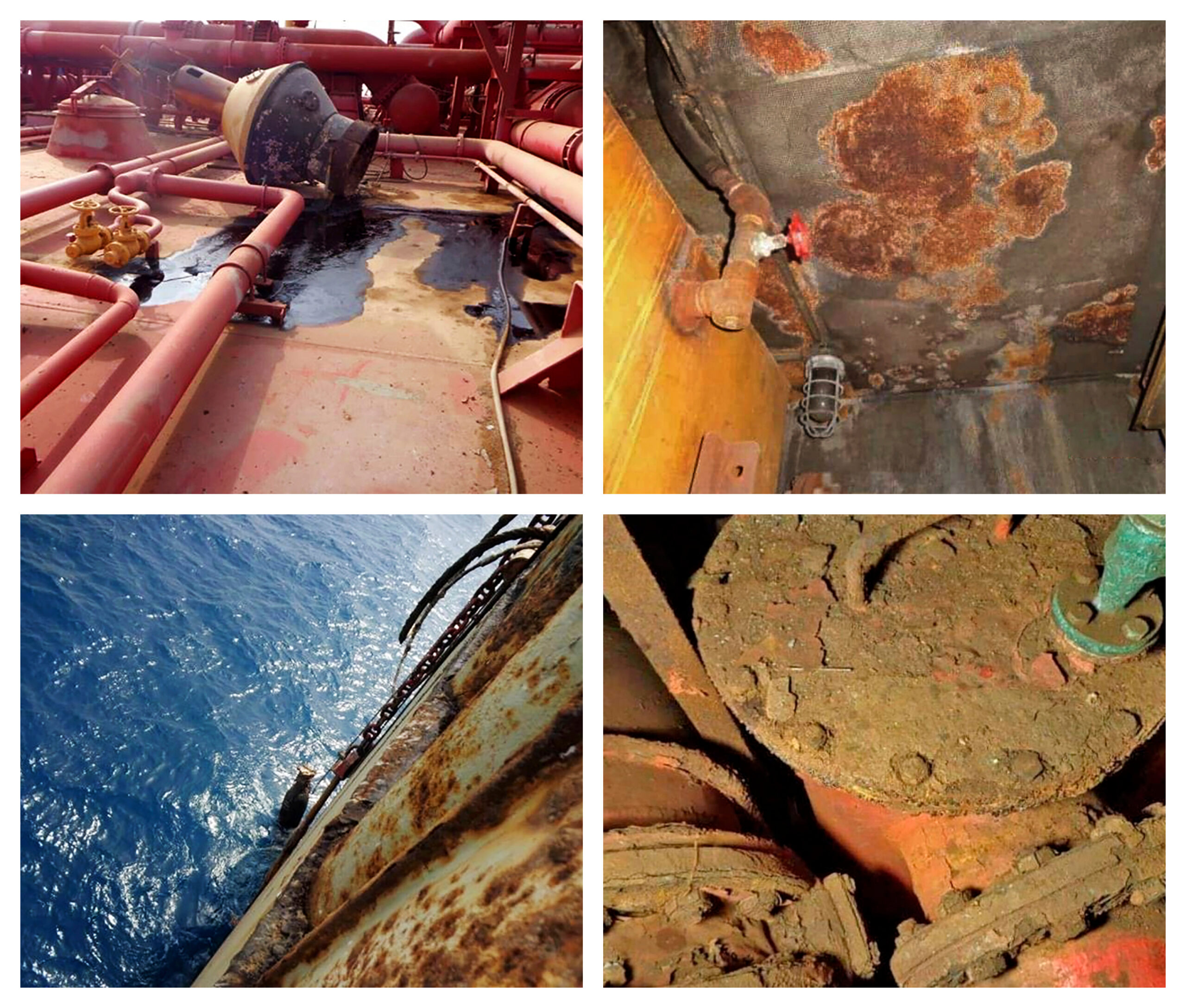

According to a team of government officials that visited the tanker, oil from the vessel could begin leaking into the Red Sea at any time. Those officials say that if any of the ship’s tanks rupture, the fallout could potentially cover an area of 939 trillion square meters (approx. 366,000 square miles), warning that the ship’s boilers and coolers suffer from severe corrosion. In fact, the United Nations has claimed that oil on the Safer may have begun leaking three months ago, stemming from a leak in a cooling pipe that sent water bursting into the engine room.

Despite opposition from most of Yemen’s political factions, the Ansar Allah-led Salvation Government in Sana’a granted visas to a UN team to visit the ship this week in response to a call by the UN for access to the ship. Many political parties saw the move as a violation of Yemen’s sovereignty and an attempt to internationalize the tanker, similar to the attempt to internationalize the Beirut explosion investigations. They say that it is not the time for visits, but to send urgently-needed maintenance equipment and spare parts.

The United Nations wants to dispatch a team, not to conduct the necessary maintenance of the ship, but to tow to an undisclosed location and dismantle it. The move is rejected by Ansar Allah, who see the survival of the tanker as a national security concern. The ship needs restoration and maintenance, not disposal, according to Hussein al- Ezi, Ansarallah Deputy Foreign Minister who accused the Saudi-led coalition of politicizing the tanker issue. “The infrastructure that Saudi Arabia has not destroyed, it is trying to destroy it in a soft manner through the United Nations,” he said.

Yet another bargaining chip

Like most other economic and aid issues in Yemen, the plight of the tanker has become a bargaining chip. Yemenis have repeatedly sounded the alarm and warned of a major catastrophe, but their warnings have been ignored. Now, they say, the United States and Saudi-led Coalition has revived the controversy in order to deprive Yemenis of the oil stored on the ship, seizing on public awareness that arose following the Beirut explosion.

An official in Hodeida who wished to remain anonymous due to the sensitivity of the situation said that there are concerns in the Houthi-led government that the FSO Safer could be bombed by local or international actors hoping to bring tensions in the Red Sea to a head. The official referred to terrorist groups, Israel and the United Arab Emirates as the most significant threats. Other political bodies in Yemen have accused the Saudi-led Coalition of politicizing the oil tanker in order to blackmail opposition forces who have made advances in the rich-oil Marib province.

In June, the UN Security Council expressed concern over “the growing risk that the Safer oil tanker could rupture or explode causing an environmental, economic and humanitarian catastrophe for Yemen and its neighbors.” Yet instead of requesting that the Saudi coalition allow the government in Sana’a to send maintenance and repair equipment, they called on the Houthis to “immediately grant unconditional access to United Nations technical experts. The Houthis eventually relented and have agreed to let a UN team access the tanker in order to avoid a spill.

Most of Yemen’s political bodies have rejected the outward concerns of the United States and UN Security Council about the fate of the FSO Safer, saying that they display interest in marine life and the environment but show disregard for the lives of the thousands of Yemenis who die in Saudi bombings. Some are calling for Ansar Allah to use the FSO Safer as a bargaining chip to negotiate an end to the war, a lifting of the Saudi blockade, or at least to allow much-needed oil to enter the country.

The Houthi-led government in Sana’a has repeatedly called for an assessment of the tanker, but those demands have been rejected. On December 21, 2016, Yemen’s Minister of Oil and Minerals asked leaders of the oil bodies and institutions to find a solution to the impending crisis. He repeated his warnings in May of 2017; the situation, however, continued to worsen. In April 2017, the General Authority for Maritime Affairs announced that the cessation of most activities, including maintenance on the floating tanker, threatens a maritime disaster that could affect Yemen and neighboring countries, but the Saudi-led Coalition showed no interest.

The Saudi-led Coalition has accused the Houthis of using the Safer as a “nuclear bomb” for bargaining since the Houthis want guarantees that the revenue from the oil onboard the tanker will go to vital facilities including hospitals, electricity, and water treatment plants which are suffering from lack of fuel due to a Saudi blockade on Yemen. The Coalition wants to keep that oil revenue, much as they have the revenue from Yemen’s southern regions where Saudi Arabia and the UAE are extracting oil from Shabwa, Balahaf, and Hadramout regions and transferring them to the National Bank in Saudi Arabia.

In 2015, when the Saudi-led Coalition military campaign began in Yemen, Saudi Arabia prevented the FSO Safer from leaving Hodeida and forced crew members to abandon it, leaving important maintenance work undone and creating what is essentially a floating time bomb. Since the vessel was abandoned, the Coalition has repeatedly prevented other ships from refueling the tanker with diesel to operate its generators used for cooling and to discharge gas emitted by the crude oil.

In 1988, SEPOC anchored the ship permanently off the Ras Essa oil port, 4.8 miles offshore from the Yemeni coast on the Red Sea, and connected it to the 430 km oil export pipeline originating from Marib. The ship was outfitted with equipment to allow the transfer of crude oil to other transshipment vessels.

The Safer soon became the main export terminal for light crude oil extracted from Sector 18 in the Safer region of Marib, east of Yemen’s capital city of Sana`a, as well as Sector 9 in the Malik area of the country’s Shabwa governorate. It is designed to undergo constant maintenance in order to prevent the build-up of explosive gases. In November of 2016, Coalition forces prevented the Safer Company’s Rama-1 ships from entering Rass Issa in Hodeida to unload 300 tons of diesel to supply the Safer FSO enough fuel to operate its generators and safety systems, according to a letter submitted by Middle East Shipping Company Limited to the Yemen Oil Company dated November 7, 2016.

Feature | An edited satellite image of the FSO Safer tanker moored near Hodeida, Yemen, June 17, 2020. MintPress | Maxar Technologies via AP

Ahmed AbdulKareem is a Yemeni journalist. He covers the war in Yemen for MintPress News as well as local Yemeni media.