SEATTLE — Adored by multitudes of Israelis for his battlefield heroism and love of the land of Israel, Rehavam Zeevi is now being portrayed as a hero with feet of clay, if not baser material.

Israel’s leading news magazine, “Uvdah,” recently aired a segment (Hebrew) that explores the darker side of the legacy of the Israeli general and cabinet minister who was assassinated by Palestinian gunmen in 2001. The program identified five women who served under his command in the 1970s, who accuse him of rape and attempted rape.

One of Zeevi’s friends recounted to “Uvdah” a conversation in which the general said: “There are three things I was made to do in life: fighting, fucking and eating.”

The news comes as a shock to the average Israeli, for whom Zeevi’s name conjures notions of courage and selflessness, not sexual predation.

As those who follow Israeli sexual politics know, women have only recently started to come forward in substantial numbers to report sexual harassment, abuse or rape. With the imprisonment of former President Moshe Katzav in 2011 on rape charges, the tide has begun to turn. And though a decade ago it would have been almost unheard of for a woman to file a complaint against a member of the elite, including members of the military and intelligence agencies, that is no longer the case.

In the 1970s many women may have been flattered by the attention offered to them by as colorful and legendary a figure as Zeevi. Songs were written boasting of his prowess. He dined with celebrities. He was the height of Israeli glamour and manliness. Victims of his apparently violent nature toward women would’ve had virtually no recourse to military authorities.

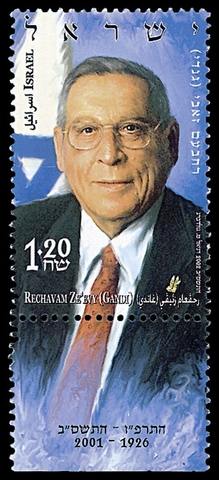

Born in Jerusalem in 1926 and raised on a collective farm, Zeevi began his military career in 1942, serving in the elite Palmach force. He participated in the infamous Operation Dani, which led to the expulsion of tens of thousands of Palestinian residents of central Israel, primarily around Lod. After the war, he continued with his military service and became a commander.

He led a 1951 operation, Tel Motila, against Syrian commandos who had penetrated into northern Israel. Over 40 Israelis were killed over the course of the four-day battle. Though Zeevi was awarded a citation for his command of the battle, he and virtually all the officers in his unit actually sat in a secure spot (Hebrew) far from the bloodbath their own troops endured. There wasn’t even a medic or doctor assigned to the unit to tend the wounded. His soldiers were largely green recruits, new immigrants who’d been drafted into the army only four months earlier. He was only a 30-minute drive from his troops, but he never showed his face during the entire battle. All he did was offer encouragement and promise reinforcements who never actually arrived. One could argue Zeevi essentially abandoned his command.

‘Gandhi’: A devout Kahanist

“Voluntary transfer — we can bring it about and encourage it without any Arab government having to agree to it. If King Hussein was smart enough to evict 60,000 Arabs each year from Judea and Samaria [sic] when it was under his rule, why shouldn’t we be able to double or triple this number? If we close the Intifada ‘universities’ in Judea and Samaria, if we end the jobs of Arab laborers from Judea and Samaria within Israel, if we stop encouraging the development of their commercial businesses, they will [voluntarily] move to other countries and remain there. That’s voluntary transfer!”

After he was named head of Central Command in 1968, Zeevi made a name for himself by hunting down commandos and armed infiltrators who crossed the Jordanian border into Israel. Though he was the senior officer and not expected to participate in raids, he would join in operations to liquidate the terror cells. He even invited his friends — actors, journalists, politicians — to join.

Zeevi’s personal military pilot recounted a story about the aftermath of one such raid during that period. Usually, he told “Uvdah,” they would take the bodies of dead terrorists and fly them by helicopter to the nearest road, where they would be picked up and transported to a morgue. But after a particularly difficult cell was eliminated in the Jordan Valley, the pilot says that Zeevi instructed him to attach the corpses of the attackers by rope to the helicopter skids and fly low over neighboring Arab villages. He apparently did this as a warning: This is what happens to Arabs who attack me.

In the 1950s, when he had been a young intelligence officer, IDF commander Rafi Eitan ordered the expulsion of Bedouins from villages near Gaza. Zeevi came upon two local Arab residents. Instead of arresting them, he shot one dead and wounded the other. Eitan reportedly remonstrated with him, saying, “You don’t kill any more than necessary.” But this was Zeevi’s way. Numerous sources in the “Uvdah” segment say of him that he “knew no boundaries.”

The IDF general was also a prodigious leaker. His favorite reporter, Eitan Haber, told “Uvdah” that Zeevi leaked “from morning till night.” And when a general leaks he doesn’t discriminate between what’s secret and what’s not. In fact, the material that such sources leak is often top secret, but by virtue of their position, they face no accountability for their actions in this regard.

‘Gandhi’ put a gun to favored journalist’s head

Zeevi could be fierce in his anger at a trusted friend or journalist who crossed him.

In the “Uvdah” piece, Eitan Haber describes joining Zeevi on a press outing to the border with Gaza. The general was especially angry with Haber for some reason Haber no longer remembers, but he does remember what came next: Sitting next to him as the bus rocked up and down over rutted back roads, Zeevi pulled out his pistol, pointed it at the reporter’s temple and told him he wouldn’t live to the end of the trip. Then he told Haber to stand before the assembled press corps and beg his forgiveness. Only after he apologized, did Zeevi lower his gun.

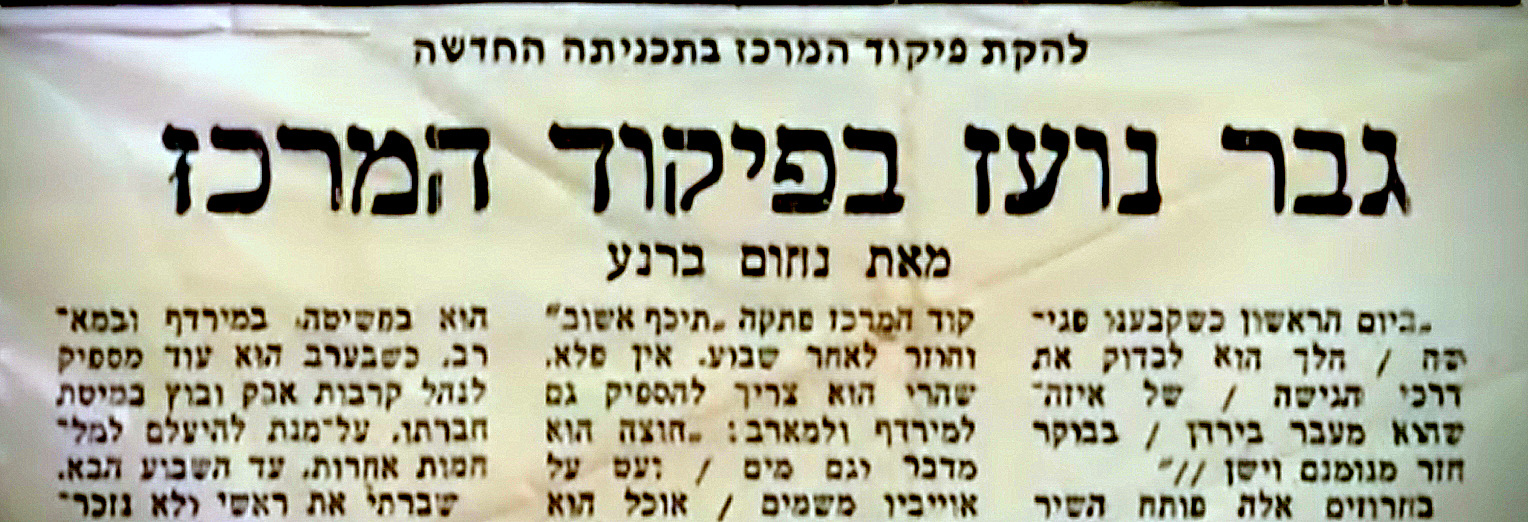

Israel’s most popular newspaper columnist, Nahum Barnea, wrote a column in the late 1960s that poked fun at Zeevi, who was immortalized in a popular song of the day. Mocking the martial heroism of the lyrics, he titled his column: ”The Bold General of Central Command.” In response, Barnea told “Uvdah,” the general and his cronies called Barnea’s home day and night, threatening him with death. The columnist had a brother who’d been severely wounded in a Fatah ambush. One caller reached Barnea’s mother and said: “Your son is dead.” She thought they were referring to her wounded son, not realizing it was a death threat against her other son. In the “Uvdah” segment, Barnea recounts the special grief this inflicted on her.

A famous television star and singer, Rivka Michaeli, told a group of reporters with whom she was having coffee after Zeevi left the army in 1974, that the retired general had lost the opportunity to be named counter-terror advisor to the prime minister because of a scandal in which he was embroiled. One of the reporters called Zeevi to check on the story. After that call, Zeevi started making calls at all hours of the day and night, threatening to kill Michaeli and her children. She says he told her that he could find her any time while she was walking on the street and rip off her dress, and threatened to blow up her home.

She told “Uvdah” that she first met Zeevi was when she was invited to a Bar Mitzvah party for his son at the home of Moshe Dayan. She exited the party early, leaving through a side gate. There, in a dark walkway, she says Zeevi attacked her, pinning her arms to the wall and injuring them. Then, as quickly as he attacked, she says, he left without even glancing at her.

Michaeli says that whenever she passes any of the myriad monuments, bridges or streets named in his honor she spits in disgust and drives on.

In 1971, Sylvie Keshet penned a savage satirical column, “The Mexican General Castanets,” in which she likened Zeevi both to a Roman emperor and a Latin American dictator. Translated from Hebrew, it reads:

“The celebrated army of the Mexican General Castanets, the envy of all Latin America:

The Mexican General Castanets, a disciple of those revolutionaries, Villa and Zapata, continues the tradition of luxury of the heroic, democratic people’s army, by building an astounding, luxurious fortress costing more than $17 million. The Mexican General takes care that not an extra centavo is spent.

When the Mexican General Castanets wishes to spend some time away from his military duties, he prepares a garden party at his home. He makes sure to share the pleasures of it with his soldiers, by volunteering them to serve his guests as waiters.

As the celebrated commander of this republican people’s army, he well understands the importance of literature and poetry contributing to the special experience of being in his army. When he oversaw the [terrorist] pursuits and hunted men by helicopter, he welcomed an entire fellowship of writers, and palace reporters, lovers of peace all.”

Following publication, Keshet was subjected to the same treatment as Barnea. Phone calls came in the middle of the night, even hourly. She received death threats. A few years went by and the terror seemed to have passed, but the general never forgot a slight.

‘Gandhi’ and the Israeli mafia

After retiring from the military in 1974, Zeevi served as military advisor to former Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and took up with Israeli mafiosi. In particular, he consorted with members of a Yemenite mafia clan. When asked why he did so, he reportedly told his interlocutor: “Look, I love women. I love to bed women. I love to fuck. They’re [the mafia] the only ones who will find me places where I can carry on in secret. That’s why I do it.”

These mafiosi became his fixer, his procurer, his enforcer, and he treated them to the good life he enjoyed as both a military hero and high-level advisor. There were fine restaurants, trips to elegant hotels in New York, and, of course, women.

His chief enforcer, Tuvia Oshri, called in a favor. A very big favor. In 1981, in the midst of a gang turf war, he and a fellow mobster committed a double murder. They needed to get out of the country fast. They called Zeevi and asked to meet him. According to a police wiretap of the call, his immediate response was: “If you need me [I’ll be there].” They did need him, and according to the mobsters, Zeevi met them and they escaped with his help. Zeevi, however, maintained that he said he would meet them, but never did.

In this case, he opened himself to considerably legal peril. He was asked to be an accomplice to murder. Though they investigated Zeevi intensely, police never charged him with any crime. This is a testament not to his innocence, but to his position as a made man, protected by his sacrosanct status as both a military hero and friend of the mob. As such, he was virtually untouchable.

‘Gandhi’ makes death threats against a future prime minister

Before he became prime minister, Ehud Olmert was making his mark as a Likud Young Turk by tackling corruption in politics and business in the 1980s. One of his targets was Zeevi. As the “Uvdah” segment so clearly demonstrates, the former general didn’t brook enemies — he went after them tooth and nail.

Maariv news report October 31, 1974, detailing bombing of the home of Israeli columnist, Sylvie Keshet. Headline: “Bomb explodes outside home of Sylvia Keshet”

Olmert, who decades later would be felled by corruption charges of his own, was no shrinking violet. He recorded death threats made against him by Zeevi and played them back on network television. Meanwhile, police wiretaps picked up warnings that Zeevi was plotting to harm Olmert.

Though the Likud’s rising star was never harmed, others were. The reporter who received serial death threats, Sylvie Keshet, faced the full force of Zeevi’s wrath. When the latter commanded his capo, Tuvia Oshri, to plant a bomb at Keshet’s home, Oshri turned to one of his mob confederates to do the job.

On Oct. 31 1974, three years after she published her article poking fun at Gandhi, Keshet was at in her Tel Aviv home with her dog as her companion. She grew alarmed as the dog began barking furiously at the front door to her apartment. She also smelled something unusual outside. The next thing she knew a bomb exploded, her door flew through the air, the windows blew out. She credits her dog for saving her life.

No one was ever charged in the bombing, though Oshri admits during his “Uvdah” interview that he organized the attack at Zeevi’s request. The IDF general had retired from active duty only four weeks before the attack. Leaving active duty apparently freed him to exact personal revenge against the journalist.

‘Gandhi’: Serial rapist

Many of these charges are old news in Israel. But “Uvdah” dug up new ones regarding rapes, attempted rapes and brutal violence which characterized Zeevi’s relations with women from his earliest days in the military virtually up until his death.

The producers recorded multiple accounts of women who served under him in the military. They say Zeevi raped or tried to rape them. Many of the alleged attacks occurred at his office in the Kirya, Israel’s Pentagon, where he had installed a Murphy (wall) bed solely for the purpose of facilitating his sexual predation. Other attacks occurred at the homes of the victims, where he often arrived uninvited and unannounced.

One woman told “Uvdah” that she was flattered that a general had summoned her to see him when she was an 18-year-old soldier. Zeevi’s personal driver picked her up and drove her to the Kirya. After she arrived at Zeevi’s office, he locked the door and pounced on her. After raping her, Zeevi redressed in his uniform and told her to hurry up and get dressed. She describes being too stunned to move. His response was: “Girlie, come on, we don’t have all day.”

He was impatient because he had an important meeting at headquarters, then he summoned his driver to take her home. The contrast between the elegance with which his driver treated her and the violence of her rape added yet more unreality to the experience, she says.

When she arrived home she told her family she’d been raped. She wanted to report it to the police, but they told her she was insane and no one would believe her. She never filed a complaint. Some time later, a personal check arrived in the mail signed by Zeevi made out in a “tidy sum.” It was a pay-off to buy her silence.

A one-time subordinate recounts that there were “tens” of women who complained to their commanding officers about being attacked by Zeevi. With the women in states of great distress, the officer would give them ten-day leave and order the victim reassigned to a different unit.

The subordinate notes that these were the victims who fought off the attacks. They could complain, but those who were raped by Zeevi were too ashamed.

‘Gandhi’ beatified in death

As horrific as all these stories and allegations are, they are not the most disturbing aspect of Zeevi’s legacy. That concerns the Israeli general and tourism minister’s murder in 2001, when he was one of the most far-right, anti-Palestinian ministers in the leading coalition government.

Shortly before his death, the IDF had assassinated the leader of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. In retaliation, the new leader determined to assassinate a sitting Israeli minister. They did so in a spectacular attack outside Zeevi’s room at the Jerusalem Hyatt.

In the aftermath of his death, Zeevi was transformed into a virtual national martyr with the help of his family and Likud colleagues. Within four years, the Knesset had passed a “Gandhi Law” (Hebrew) that ratified the murdered man’s sainthood. Millions in state funding were allocated for annual commemorations of his life and legacy. Bridges, streets and highways were named for him. Schools were directed to teach lessons based on his military exploits and avowed passion for the land of Israel. A museum dedicated to him was planned. In the decade following his death the state spent $2.5 million on such activities, including a small percentage that was allocated to honor Theodor Herzl and David Ben Gurion, universally acknowledged as the founders of Zionism and the state of Israel, respectively.

Zeevi has been elevated to the Zionist pantheon, but his military legacy is entirely fraudulent. He was not an especially gifted officer. He showed no special strategic skills. He won no great battles. His military specialty was hunting down poorly armed Arab infiltrators and eliminating them.

His personal legacy was one of sexual predation and violence. Add to that his sordid history of association with the criminal underworld and you get a thoroughly disreputable, even monstrous, human being.

How is such a disconnect possible? How can an entire nation permit itself to be fooled into transforming a criminal into a saint? It would be as if the United States decided that it wasn’t George Washington, but Al Capone who was the nation’s true father. Can anyone imagine this as possible?

In Israel it is. Remember, this is a nation founded on violence, including crimes of sexual violence, as noted by Benny Morris in his historical research, founded on mass expulsion and racism. A nation conceived not in liberty, as Abraham Lincoln noted of American origins in his Gettysburg Address, but in the Original Sin of Nakba. Is it any wonder that such a nation would permit itself to be deluded into worshipping a murderer and turning him into a national idol?

Zeevi, his family and the nation made an unholy bargain. In life, he was a hooligan, but in death, the nation could project all of its patriotic ideals onto him as if he were a palimpsest. He became what the nation needed: a hero, pure and brave. Not a real person. Not an accurate portrait.

Zeevi, in fact, became a highly marketable product, which his family has turned into an industry. In much the same way that, as Norman Finkelstein noted, Jewish organizations have transformed the Holocaust into an industry that offers them a raison d’etre.

Zeevi, whose unlikely nickname was “Gandhi,” espoused Kahanist views, including ethnic cleansing of the indigenous Palestinian population. It is commonly and more euphemistically called “transfer” (as in “population transfer”) in Israel. Here, translated from Hebrew, is one of his classic formulations of the idea: