The woman whose name became associated with the David Petraeus sex scandal is speaking out against the government’s overreaching spy program, claiming the government violated the Privacy Act and her Fourth Amendment rights.

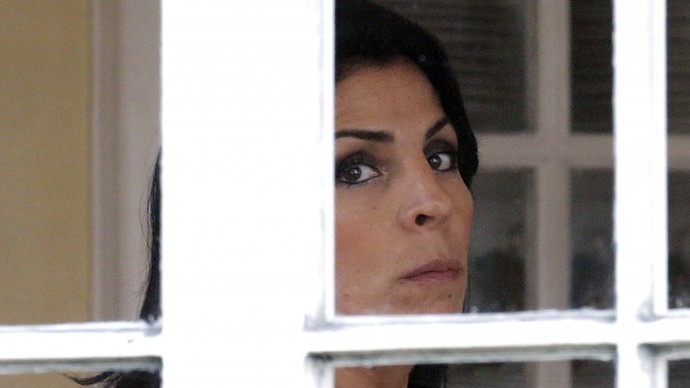

Jill Kelley was brought into the spotlight after information she reported to the FBI led to the discovery of the affair between former CIA director Petraeus and his biographer and Army officer, Paula Broadwell. Kelley, who enjoyed a friendship with Petraeus, contacted the FBI over a series of anonymous and threatening emails she and her husband were receiving.

Kelley claims she and her husband authorized the FBI to view one email, as it included threats made against not only her and her family, but others, including to people she refers to as U.S. officials. The investigation discovered the emails were being sent by Broadwell, yet the digging didn’t stop there.

The FBI’s investigation not only revealed the affair between Petraeus and Broadwell, but alleged that Kelley, too, was part of a scandal.

During their investigation into Kelley’s emails, the FBI uncovered conversations between she and Gen. John Allen, a close friend. An anonymous source with the FBI told reporters the emails could be considered inappropriate, starting a frenzy of accusations directed at Kelley and Allen. Both deny having an extramarital affair.

This is where Kelley claims the FBI crossed the line.

“We authorized the FBI to look at one threatening email we received, and only that email, so that the FBI could identify the stalker,” Kelley wrote in a Wall Street Journal opinion piece. “However, the FBI ignored our request and violated our trust by unlawfully searching our private emails and turning us into the targets of an intrusive investigation without any just cause—all the while without informing us that they had identified the email stalker as Paula Broadwell, who was having an affair with Mr. Petraeus.”

In June, Kelley and her husband filed suit against the FBI, the Pentagon and undisclosed federal agents for allegedly violating her Fourth Amendment rights and leaking her name and misleading information to the public.

Cyberstalking charges brought against Broadwell were eventually dropped

Tying her case to need for privacy

Kelley has long pointed her finger at the FBI for violating her rights and spreading false information to taint her name, which she says caused her and her family a great deal of pain.

Now she’s using the issue to highlight a problem she sees in the U.S., tying it to the National Security Agency scandal. In May, previously unknown programs in the NSA’s spying system were revealed by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden, who leaked documents detailing the elaborate programs to The Guardian.

The scandal caused an uproar among American citizens and Fourth Amendment rights advocates, citing the leaked information as proof the government was — and is — acting outside the constitution.

Kelley is now among those voices.

“More recent revelations of National Security Agency spying suggest that the government’s invasion of citizen’s privacy is increasingly common,” she wrote. “Millions of innocent Americans should be very concerned about Washington’s massive surveillance apparatus, which seems to know no bounds.”

In late September, the Justice Department moved to have the lawsuit brought on by the Kelleys dismissed, claiming the lawsuit failed to indicate the FBI or any other government body violated Kelley’s rights.

Yet their lawyer, Alan Raul, told CNN that the Kelleys would continue to press their case against the FBI, not only to bring about justice, but to create an atmosphere where those going to the FBI with information feel safe and confident doing so, without risking their rights being violated.

“As painful as my experience has been, it has motivated me to be an advocate against unwarranted spying on personal communications, and to push for new legislation and better enforcement of existing privacy laws,” Kelley wrote. “Congress should strengthen the Privacy Act, update the Electronic Communications Privacy Act. Americans’ Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable search and seizures should be extended to personal communications.”

The Privacy Act was created in 1974 to address concerns related to the collection of computer database systems and the potential impact they would have on citizens’ rights.

According to the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC), the Act “safeguards privacy through creating four procedural and substantive rights in personal data.” Under the Act, government agencies must show individuals records kept on them, while also mandating agencies follow fair information practices. It also limits agencies from sharing personal data with other agencies and allows those who feel their privacy rights have been violated to sue the government.

The one catch to the Privacy Act, however, is that it allows government agencies that are involved in law enforcement to disregard the Act, according to EPIC.

In the name of national security?

After Snowden blew the whistle on the NSA’s secret surveillance programs, the agency went on the offensive. In June, a month after the Snowden leaks, the agency planned to release a list of potential terrorist activities thrwarted through the agency’s surveillance programs.

The goal was to show Americans that the NSA wields the power it possesses to effectively keep the U.S. safe from terrorist threats. It’s similar to arguments used by the FBI and other federal law enforcement agencies.

Yet, as Kelley points out, the FBI’s alleged unwarranted dive into her email account had nothing to do with national security.

“The country is not safer after reading my emails. The humiliation of and damage to my family should never have occurred. By raising public awareness and holding the government accountable, my husband and I hope we will help protect other innocent families from intrusive government snooping,” Kelley wrote in the WSJ. “The invasion of privacy that my family endured from the federal government is not unique. Nevertheless, it is un-American.”

Kelley is acknowledging that the FBI investigation was set off after she contacted the bureau, but in her opinion piece, she warned the American people to not feel confident their communications privacy will be protected, claiming there’s no shortage of excuses federal law enforcement could use to access personal data.

“With all the current economic, political, social and diplomatic issues facing the country, it is understandable that many Americans seem relatively unconcerned about intrusions on individual privacy. They shouldn’t be,” she wrote. “The unauthorized search of my family’s emails was triggered when we appealed to law enforcement for protection. But who knows what else might set off governmental invasion of privacy—politics or some other improper motivation might suffice. If this could happen to us, it could happen to you.”