(ANALYSIS) — Although it obstinately insists pipelines are safe, the company responsible for the Dakota Access Pipeline racked up 69 reported accidents in just two years — leaking hundreds of thousands of gallons of oil products and tainting rivers in four states.

That averages nearly three spills each month.

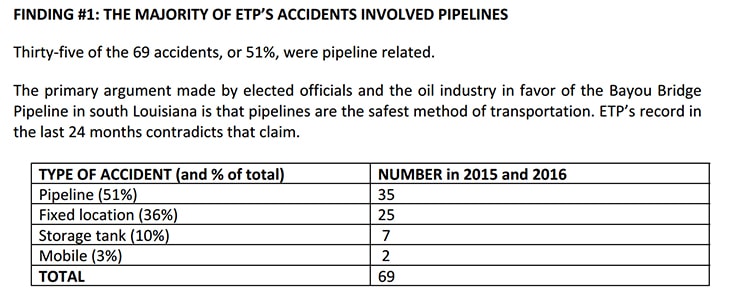

A new report from the Louisiana Bucket Brigade and DisasterMap.net on Energy Transfer Partners and subsidiary Sunoco Logistics documents accidents filed with the National Response Center — the federal contact point for oil spills and industrial accidents — noting 69 accidents between 2015 and 2016.

However, as the study crucially notes, “These are just the accidents that are reported.”

“Heavy rain was the explanation for some of the worst accidents,” the report states, noting, “Bad weather, however, just exposes faulty equipment. While Energy Transfer Partners and other companies portray weather-related accidents as unavoidable, they are in reality a result of poor planning and neglected maintenance. For example, the largest tank fire in history happened in South Louisiana in 2001. Because it occurred during a storm, Orion Refining blamed the weather. In truth, a faulty drain on the tank sank the roof, exposed the gasoline and attracted lightning.”

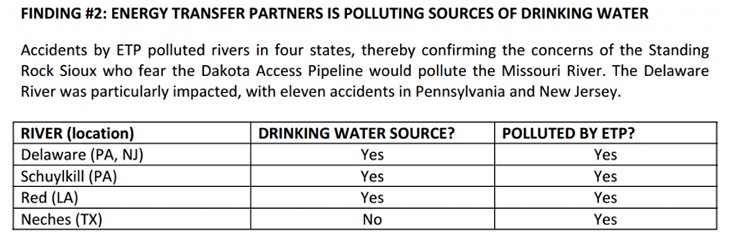

According to the report, ETP’s horrendous track record over the two-year period in the analysis — including the contamination of the Delaware River in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, the Schuylkill River in Pennsylvania, and the Red River in Louisiana — “thereby confirm[s] the concerns of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe who fear the Dakota Access Pipeline would pollute the Missouri River.”

“Sunoco and ETP accidents stretch from Texas to Massachusetts,” asserted Dr. Ezra Boyd, a geographer with DisasterMap.net who analyzed data for the report. “While these accidents cover a large area of the map, the Bayou Bridge pipeline would put an entirely new area at risk: South Central Louisiana, including the Atchafalaya Basin.”

EcoWatch reports:

“Dallas-based Energy Transfer Partners owns about 71,000 miles of natural gas, natural gas liquids, refined products and crude oil pipelines across the country.

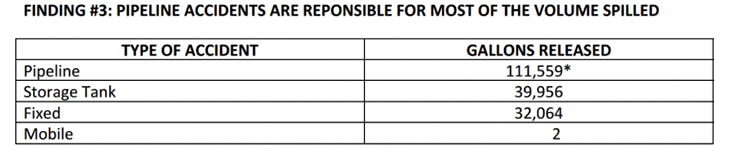

“The report lists 42 known oil spills, 11 natural gas spills, nine gasoline spills, three propane spills, two ‘other’ spills and two ‘unknown’ spills. Those 69 incidents led to eight injuries, five evacuations and a total damage dollar amount of $300,000. In all, the total known amount of various substances spilled was 544,784 gallons.”

Pipeline companies and the oil and gas industry contend pipelines are the safest means of transporting fossil fuels — and, in comparison to rail and tanker truck methods, they are technically correct.

However, while pipeline accidents occur less frequently, the quantity of oil released tends to be far larger, given the substance is under pressure to flow through the lines and equipment tasked with sensing and stopping leaks doesn’t always function properly — meaning many accidents in desolated areas aren’t discovered immediately.

Take the case of a North Dakota wheat farmer less than two miles from where water protectors remain encamped in opposition to the Dakota Access Pipeline, which will run under the Missouri River’s Lake Oahe reservoir and could threaten the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation’s water supply, and that of around 18 million people downstream.

In 2013, Steve Jensen discovered thick, black, crop-killing crude contaminating a distant corner of one of his wheat fields — not realizing at the time a pipeline under the property had bled nearly one million gallons of the hydrocarbon. Tesoro Corporation got the alert for the spill from Jensen, not from remote pipeline sensors as it should have, and has since dug 50 feet in some areas to alleviate the environmental nightmare sprawling across the land the size of 13 football fields.

Now estimated to soar to $60 million, the cleanup isn’t projected to ever reach full completion.

Incidentally, that spill — and a second belching 176,000 gallons into Ash Coulee Creek — were the handiwork of six-inch steel pipelines. Dakota Access, in comparison, is a 30-inch steel pipeline slated to transport nearly 20-million gallons — daily.

Nasty track record aside, ETP has nearly completed construction on DAPL — to the condemnation of the Standing Rock Sioux and a global movement of water protectors seeking to halt all new fossil fuel infrastructure and shift to renewable energy. And DAPL, like the Tesoro pipeline under the Jensens’ field, will be located underground in bedrock — something ETP claims is the safest possible method of crossing the Missouri, no matter the evidence to the contrary.

This week, the final battle to halt Dakota Access began winding down in federal courts after the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers granted the easement necessary for ETP to complete the pipeline.

A judge denied the tribe’s request for an emergency restraining order to stop ETP from drilling under the river — but a new motion was filed by the tribe on Tuesday, attempting the same, under the premise an imperative environmental impact study should have been carried out as promised.

Dakota Access isn’t the only controversial pipeline project on Energy Transfer Partners’ roster — the Trans-Pecos Pipeline in Texas and Bayou Bridge Pipeline in Louisiana have sparked new encampments like those in Standing Rock as water protectors branch out from North Dakota.

With such an atrocious safety and spill record under its belt, Energy Transfer Partners seems so hell bent on profiteering, potential destruction of the environment matters little — if at all.

“Energy Transfer Partners’ records contradict their claim that pipelines are a safer way of transporting oil,” Renate Heurich of 350 Louisiana told EcoWatch. “Pipelines make transporting tar sands cheaper, thus stimulating dirty tar sands extraction despite low oil prices. The real question is: Why do we still invest in more pipeline infrastructure when we urgently need to invest in sustainable alternative energy sources?”

The real answer is simple, at least when it comes to ETP: profit from foreign markets. In preparing to construct the Dakota Access Pipeline, ETP worked furiously behind the scenes to ensure a ban on the export of unrefined crude in place since the 1970s would be lifted specifically so the company could cash in on exporting the Bakken sweet, light crude it would carry.

That single act of surreptitious legislative legerdemain opened the crude and cash floodgates for Big Oil — nearly guaranteeing the fossil fuel industry will opportune the chance to run roughshod over anyone or anything in the way of profit, while duplicitously claiming in the face of evidence otherwise that pipelines are perfectly safe.