Long before the National Security Agency was caught electronically surveilling Americans without first obtaining a warrant, local law enforcement agencies in about 15 states had been using technology to collect information from nearby cellular devices — also without obtaining a warrant.

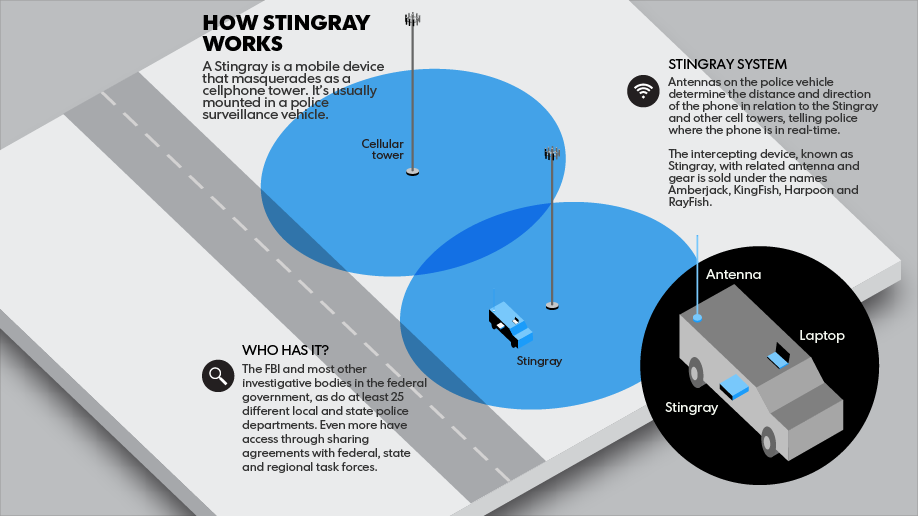

Known as a Stingray, the suitcase-sized surveillance tool imitates the abilities of a cell phone tower and essentially forces all cellular devices within a one-mile radius to connect to the “tower.” When the devices connect to the artificial cellular tower, all data being sent to and from the devices is fed into a police database.

Because it is small, a Stingray is often installed into law enforcement vehicles so that the device can easily be transferred from neighborhood to neighborhood in order to collect information.

Each device costs between $250,000 and $400,000. Some local police departments are not able to foot the bill for the technology, though, so they borrow the funds from state surveillance units. However, departments usually receive help purchasing the technology from the federal government, via anti-terror grants.

The technology has been used for years, unknown to not only the public, but also many defense attorneys and judges. For example, in Sacramento, California, a local ABC affiliate recently conducted an investigation into use of the technology and found that the Sacramento County District Attorney’s Office and Sacramento Superior Court judges had no idea Stingrays or similar surveillance tools were actively being used in Sacramento.

No one knew that the technology was being used partly because police officers were not required to obtain a warrant before using it. When the officers are asked to disclose to a judge or in a warrant request where they obtained incriminating information, they were instructed by the U.S. Marshal Service to explain that they “received the information from a confidential source.”

Last month, it was revealed that the Marshal Service had actually instructed law enforcement officials in Florida, via email, to deceive judges and defendants about where the officers obtained the information they had collected with the Stingray technology.

Currently, Stingray technology is used by police departments in Alaska, Arizona, California, Florida, Illinois, Indiana, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Texas, Virginia and Wisconsin, but because of the secrecy surrounding the application of the surveillance equipment, it’s definitely possible that officers in other states could also be using the technology.

According to documents obtained by the Sacramento-based News10 team, including an invoice from the Harris Corporation, which sells the bulk of the Stingray technology to law enforcement agencies, every agency that purchases the device must sign a nondisclosure agreement stating that the “capabilities” of the technology are “not for public knowledge.”

News10 also obtained an invoice from Harris Corporation showing that the Sacramento Sheriff’s Department, who investigative journalist Thom Jensen says couldn’t get their story straight, had purchased a high-powered antenna that would extend the range of the Stingray technology to more than one mile. (Exactly how far the “Harpoon” technology amplifies the Stingray’s capabilities is not known.)

Law enforcement agencies often cite public records exemptions as reasons why they cannot disclose information about the use of the technology to the public. Jensen says the Sacramento Sheriff’s Department cited a law designed to protect railroads as a reason why the department would be exempt from answering any questions about the Stingrays, including confirming whether or not the department has and uses the technology.

While law enforcement agencies also refuse to share why they use the technology, documents obtained by News10 show that officers in Oakland, California, often use the technology to gather information related to a range of crimes, including investigations into murders, child abductions and fugitives.

For many privacy advocates, the concern about the widespread use of the surveillance technology is that it constitutes a violation of Americans’ constitutional rights. As the Electronic Frontier Foundation, an organization advocating for digital rights, wrote in 2012, “[T]hese devices allow the government to conduct broad searches amounting to ‘general warrants,’ the exact type of search the Fourth Amendment was written to prevent.”

“A Stingray — which could potentially be beamed into all the houses in one neighborhood looking for a particular signal — is the digital version of the pre-Revolutionary war practice of British soldiers going door-to-door, searching Americans’ homes without rationale or suspicion, let alone judicial approval.”

Since the Supreme Court ruled 9-0 last month that warrants must be obtained in order to search a cellphone, privacy advocates hope that this is a step in the right direction toward protecting Americans freedoms and rights.

“I don’t think that these devices should never be used, but at the same time, you should clearly be getting a warrant,” said Alan Butler of the Electronic Privacy Information Center.