BUZZARDS BAY, Mass. — On yet another dark anniversary of the day that changed the world, the United States finds itself once again in crisis.

The events in Syria have shocked and sickened all who have seen the horrific videos of children gasping for life, of men and women foaming at the mouth, of stacks of white-shrouded bodies awaiting burial.

It’s clear that something must be done. What’s much murkier is what kind of action can help alleviate the suffering and try to ensure that it never happens again.

Even before the chemical attacks near Damascus, Syria’s tragedy troubled the world’s conscience. More than 100,000 people have died in less than three years of brutal civil war, with 6 million more displaced.

It’s increasingly apparent that some elements of this tragedy have their roots in America’s response to those September attacks.

The 12-year “Global War on Terror” exacerbated sectarian tensions across the region, stoked fears of Western aggression in the Muslim world, and gave already militant jihadists a focus for their anger and belligerence. Many of these fighters found their way to Syria, where they helped organize resistance to the Baathist regime of Bashar al-Assad.

But as the US endeavors to reassert its position as the world’s moral compass, memories of the past decade stand firmly in the way. Its citizens are no longer so eager to rush into conflict in a distant country that’s not a direct threat to the homeland. Nor is the rest of the world as willing as it once may have been to accept Washington as an honest broker.

The reasons for the shift in perceptions, both at home and abroad, can be traced to the series of deceptions and missteps that have plagued US foreign policy since 9/11.

When the second plane crashed into the South tower at 9:03 a.m. on Sept. 11, 2001, something fundamentally shifted in the American psyche. The first plane could have been a horrible accident; two in such quick succession meant, unbelievably, America was under attack.

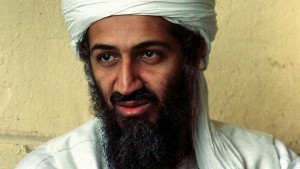

Everyone remembers the flood of patriotism and grit that followed those September days. Overpasses were festooned with flags; small schoolchildren took oaths to find and kill Osama bin Laden.

But behind the scenes, the maneuvering had already begun. Records show that Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld was planning to link Iraq’s ruler, Saddam Hussein, to 9/11 within hours of the attacks — facts be damned.

Within three days President George W. Bush had Congress’ authorization to use “all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on Sept. 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons, in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizations or persons.”

This was a very large blank check that the administration lost no time in cashing.

Bush ordered the Taliban to hand over Osama bin Laden or face the consequences. When the Taliban asked for proof of bin Laden’s involvement, Bush declared: “There’s no need to discuss innocence or guilt. We know he’s guilty.”

The Taliban did not agree.

The war in Afghanistan began on Oct. 7, less than four weeks after the first plane hit New York. Within a little more than a month, it was “over”: At Tora Bora, the last Taliban, along with Osama bin Laden, scampered over the border into Pakistan, and America’s ally, the Afghan Northern Alliance, took Kabul. As far as the United States was concerned, the war was won.

But it wasn’t that simple: Afghanistan defied Washington’s prescriptions for a bright, democratic future, and within four years a full-blown insurgency was in place, launching a round of hostilities that continues to this day.

While Afghanistan ticked along with minimal resources and scant attention from Iraq-focused Washington, the Bush administration was drumming up support for its planned attack on Saddam Hussein, citing the “weapons of mass destruction” with which the dictator was allegedly holding the world hostage.

In his State of the Union address in 2003, Bush trumpeted Saddam’s attempts to purchase uranium from Niger. Aluminum tubes were spotted that could “only” be suitable for a nuclear weapons program.

Those who bucked the party line, like Ambassador Joseph Wilson, who insisted that the Niger uranium story was a hoax, had their lives destroyed. Wilson’s wife, CIA officer Valerie Plame, was exposed, setting off a media witch hunt that sent a New York Times reporter, Judith Miller, to jail for 12 weeks.

Even the administration’s loyal foot soldiers suffered. Secretary of State Colin Powell, who made the case for war to the United Nations Security Council in February 2003, saw his integrity questioned and a blameless record forever tainted.

As TV satirist Stephen Colbert put it so succinctly just last week:

“I miss George W. Bush. That man knew how to sell a war. [He] got an international coalition with nothing more than Colin Powell’s reputation and half a test tube of crystal light.”

The Iraq war proper began in March 2003, with a campaign of “shock and awe.”

Again, America’s overwhelming might seemed to carry the day: on May 1, 2003, President Bush announced the end of combat operations in his “Mission Accomplished” speech.

Of course the worst was still to come. The conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq, with the accompanying “covert” drone campaigns in Pakistan and Yemen, deepened feelings in the region that the United States was, despite protests to the contrary, at war with Islam.

Clumsy political maneuvering by Washington also exacerbated the crises, setting ethnic groups against each other in Afghanistan, and exploiting centuries-old Sunni-Shia Muslim tensions in Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon.

Perhaps worst of all, the post-9/11 “Global War on Terror” provided a rallying point for militant jihadists everywhere. Much as Afghanistan’s war against the Soviets in the 1980s provided the training ground for groups that would become the Taliban and Al Qaeda, America’s ill-considered military adventures served as a deadly playground where militants could hone their skills and refine their philosophies of hate.

They then fan out to conflict points such as Syria, where they find a ready audience for their propaganda.

According to researchers Peter Bergen and Paul Cruikshank, the Iraq war has been particularly destructive in this regard.

“Since the invasion of Iraq, attacks by [jihadist] groups have risen more than sevenfold around the world,” they write in their report “The Iraq Effect.” We will be living with the consequences of the Iraq debacle for more than a decade.

When George W. Bush took the helm from Bill Clinton in 2001, the United States was the undisputed leader of the world.

Russia was still licking its wounds from its own implosion in 1991, caused by its misadventures in Afghanistan, its miserable economy, and a population that, thanks to the Internet and social media, could no longer be isolated.

Vladimir Putin replaced a decrepit Boris Yeltsin on Jan. 1, 2000; from that moment Russia began its comeback on the world stage.

A young and charismatic Barack Obama moved into the Oval Office in 2009, determined to chase away the ghosts of the previous administration and restore some of America’s lost luster.

He started a new policy of openness toward the Muslim world designed to quiet fears that the US was at war with Islam. This raised expectations abroad while infuriating many at home.

When a young Tunisian street vendor named Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire on Dec. 17, 2010, he ignited a wave of protest throughout the Middle East that became known as the Arab Spring.

Obama should have been in a perfect position to help.

Instead, he’s criticized for passivity during Iran’s 2009 “Green Revolution,” for “leading from behind” in Libya, for dithering during Egypt’s recent crises, and now for conflicting messages on Syria.

Obama was riding high on May 2, 2011, when US Navy Seals mounted the raid that killed Osama bin Laden. But his image has taken more than a few hits since that golden time.

Even his staunchest allies were a bit put off by revelations from US spy agency leaker Edward Snowden, who showed the world the extent of Washington’s snooping — and not only on its enemies.

So, when Obama appeals to the world’s conscience, asking that they support and follow him into Syria based on his heartfelt assurances that he has proof of the Assad regime’s perfidy, there are few ready takers.

Russia is on the ascendant, the world is skeptical, and the American public is obstinately opposed.

It has been a long and twisting road, but it all goes back to that bright September morning in 2001, the day that the world changed.

Journalist Jean MacKenzie worked as a reporter in Afghanistan from October 2004 to December 2011, first as the head of the Institute for War and Peace Reporting, then as a senior correspondent for GlobalPost.

This article originally appeared on Global Post.

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect MintPress editorial policy.