The verdict in the trial against former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak is due to be pronounced on June 2. Mubarak is accused of complicity in the killing of more than 800 demonstrators during the 18-day popular uprising that ousted him from power in February 2011. A guilty verdict could potentially send the former strongman, who ruled Egypt for nearly 30 years, to the gallows. A not guilty verdict could set the stage for another round of street protests that would undoubtedly turn violent. In either case, Mubarak’s legacy will most likely be forever tarnished, and any good he did for the country will be erased by whoever takes over the reins after him. When Gamal Abdel Nasser came to power in 1952, after deposing King Farouk, history books passed over the 140-year Mohammed Ali Dynasty like it never existed. It took decades before some of the monarchy’s achievements were acknowledged.

As a veteran Middle East news photographer, I photographed all Arab leaders on numerous occasions. Of all these autocrats, Mubarak was the one I documented the most and considered the most personable. From the mid-1980s until 2007 I covered the Egyptian leader during his countless meetings with heads of state, at Arab and African summits, as well as at official openings of book fairs, museums and sporting events. Besides the official photo ops, I had the opportunity to photograph Mubarak during numerous one-on-one interviews with publications, like the New York Times and the German weekly magazine, Der Spiegel. Sometimes, the interviews were held at the presidential palace and other times at one of Mubarak’s official residences. Normally, after the interviews were finished, there was time for joking and an informal chat with the president. One time, Mubarak asked me a few technical questions about photography and on another occasion he jokingly said I should be given Egyptian nationality because I had lived in the country for so long. Other members of the press also recognized the approachable side of Mubarak. An American journalist, and long time resident of Egypt, once asked the Egyptian leader a legal question concerning a house he had just purchased in the Sinai.

Even though the small talk didn’t amount to much, it did make me stand out in a crowd. At one of the Mubarak press conferences, I got into a scuffle with a TV cameraman and presidential security had to intervene to contain the situation. As I was being escorted out, Mubarak, who was answering some reporter’s question, turned towards me and told the security guard to let me go. He then scolded me in front of all my colleagues making me feel like a naughty boy who was being reprimanded for getting into a fight. If I hadn’t had some sort of relationship with the president he probably would not have intervened on my behalf.

It’s been over a year since Mubarak was forced to step down from office by angry protesters and a reluctant military unwilling to stand behind him. It is still hard for me to believe that after nearly 30 years at the top, his departure would come about in such a tragic way. Like most Egyptians, I was convinced that he would follow in the footsteps of every other pharaoh that has controlled Egypt and rule until he died on the throne.

Over the course of the last three decades, Mubarak has managed to break away from the shadows of his two charismatic predecessors, Abdel Nasser and Anwar Sadat. At the same time, the former air force commander was slowly consolidating his power by using his influence with the military to secure his political ambitions and dominance over the parliament. By having the assembly and military in his pocket, his leadership was seemingly unchallenged. However, there were a few breaches in his protective bubble.

In 1986, police conscripts took to the streets of Giza and began to riot, following a rumor that their serving time had been extended by a year. The conscripts burned down a number of luxury hotels at the base of the pyramids and rampaged and looted local businesses. With the regular police unable to quell the violence, Mubarak turned to his popular Defense Minister, Abdel Halim Abu Ghazala, and in a matter of hours Abu Ghazala’s troops had cordoned off all of Giza and restored calm, earning the population’s stamp of approval. Abu Ghazala, who was already a hero for having fought in all the Arab-Israeli wars, was also seen as a strong contender to succeed Mubarak. Much to everyone’s surprise, Abu Ghazala was sidelined two years later and replaced by the very uncharismatic Mohammed Hussein Tantawi, who remains the Defense Minister to this day. Officially, Abu Ghazala was relieved of his duties because of his involvement in a scandal involving illegal arms shipments to Afghanistan, but many speculate that the real reason for his dismissal was the threat he posed to the Mubarak presidency.

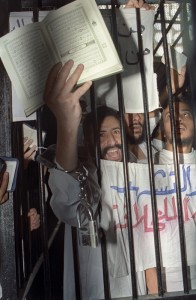

There were other examples that revealed the Egyptian leader’s vulnerability. In the early 1990s Islamists led by al-Gamaa al-Islamiya (Islamic Group) spearheaded a violent campaign to topple Mubarak’s secular regime. They targeted government ministers, intellectuals and foreign tourists and over the course of a few years turned Egypt from one of the most stable countries in the region to a war zone. In an effort to curb the attacks, Mubarak purged the interior ministry and put his cronies in charge. Police swept through the slums of Cairo, Alexandria and all along the Nile, making indiscriminate arrests. In order to bypass the often slow and bureaucratic civilian courts, military tribunals were set up to deal with the number of people accused of terrorism. In 1993 alone, nearly 50 convicted Islamists were sentenced to death and swiftly sent to the gallows a few months after their conviction. Events climaxed in June 1995 when Mubarak’s convoy came under attack in the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa, where he was attending an African Union summit. Nobody in Mubarak’s entourage was hurt in the skirmish and the attackers were killed. The Gamaa claimed responsibility for the attempt.

Unlike Egypt’s revolutionary president, Abdel-Nasser, and to some extent Sadat, Mubarak rarely mingled with the crowds or rode in open limousines. Instead, he traveled under heavy security followed by television cameras wherever he went so that his exploits could be beamed on TV and watched in every home. In many ways, Mubarak’s security concerns were legitimate, considering that he was sitting next to Sadat, when the latter was assassinated, and narrowly escaped death himself.

Mubarak had a funny and often peculiar way of appealing to the people. During the early 1990s, when Egypt’s tourist industry was suffering as a result of the Islamist insurrection, Mubarak made a surprise visit to the Red Sea resort of Sharm el Sheikh, where he strolled down one of the beaches and began chatting up the few tourists who were sunbathing. His questions were unsophisticated and very similar to those that tourists were repeatedly asked on their visits to the tourist bazaars: “Where do you come from…. Do you speak English…. Did you visit the Pyramids…. Do you like Egypt.” Some of the tourists were in hysterics, shocked by the presence of the country’s head of state walking up and down the beach looking to make conversation.

In one of his parliament addresses in 1993, when the country was in the midst of its terror campaign, Mubarak suddenly veered from his written speech to give advice to fruit and vegetable vendors on how important it was to present their produce in an attractive way. He advised them to stack their fruits in the shape of a pyramid as opposed to leaving them scattered all over the stand.

In many ways, Mubarak had a street-smart appeal about him that the average Egyptian could identify with. Unfortunately, the longer he stayed in office the more he distanced himself from the street and the average Egyptian, in particular the youth who make up the vast majority of the population.

No matter what fate lies ahead for Mubarak, it would be unfortunate if history only focused on his downfall and wiped out his achievements. Any evaluation of Mubarak’s reign would be slanted if it was not considered within the proper perspective. Mubarak ruled Egypt at a time when dictatorship in the Arab world was the norm, not the exception, and of all the tyrants in the region, Mubarak was one of the most reasonable. His fatal flaw was that he failed to face the reality of his own mortality and step down gracefully, making room for the new generation. Had he done this a decade ago, he would have been remembered as a hero, not only in the eyes of Egyptians but also the rest of the world.