The question of immigration reform has become the most volatile hot potato in Washington this electoral cycle. With the divide widening between those who seek to draw Hispanic and immigrant votes and those desperate to ingratiate themselves with the anti-immigration community, the current situation — which includes both unescorted children and mothers with their young children in tow flooding the U.S. border from Central America — has done little to encourage the passage of legislation.

The question of immigration reform has become the most volatile hot potato in Washington this electoral cycle. With the divide widening between those who seek to draw Hispanic and immigrant votes and those desperate to ingratiate themselves with the anti-immigration community, the current situation — which includes both unescorted children and mothers with their young children in tow flooding the U.S. border from Central America — has done little to encourage the passage of legislation.

It has, instead, led to charges that the president has abused presidential power in his use of executive actions to control immigration issues and an intraparty civil war which saw one of the most turbulent Republican primary seasons in recent memory — which resulted in the defeat of former House Majority Leader Eric Cantor.

In the crossfire of this political wrangling, meanwhile, is the legal status and livelihood of the nation’s more than 26 million immigrants who have not been granted legal permanent residence. Among these are the 500,000-plus youths and young adults enrolled in the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program — a U.S. Department of Homeland Security program that delays immigration removal actions and grants temporary Social Security numbers and work permits for immigrants who came to this country as children.

With net immigration from Mexico at or below zero, the individuals targeted by the current political infighting are those who have been in the United States for five years or more and have grown to call it their only home.

According to the Pew Hispanic Center, about 80 percent of all immigrants residing in the U.S. illegally come from Latin America, with 57 percent of the national total coming from Mexico alone. This is countered by findings from a January study from the think tank Mexicans and Americans Thinking Together, which found that — despite an escalation of deportations under the Obama administration — only 11 percent of all emigration to Mexico is the result of government action. Overwhelmingly, most of the non-permanent resident immigrants from Mexico who returned to Mexico chose to do so of their own volition.

“There have been decreases in both unauthorized immigration attempts at the Southwest border and border apprehensions in the last two years,” said Marc Rosenblum, deputy director of U.S. Immigration Policy at the Migration Policy Institute, to MintPress News. “Since 2007, there has been a sharp decrease in illegal immigration, compared to an increase between the 1990s and 2007. This is the product of one-third the American economic downturn, one-third increases in Mexico’s economic strength, and one-third American immigration legislation.”

This, of course, begs the question of why. But there’s also another, more important question: What does this say about the state of the nation and the state of civil rights?

The immigration question

Michele Garnett McKenzie is the advocacy director for The Advocates for Human Rights, which offers legal aid and other services to refugees and immigrants. In conversation with MintPress, McKenzie argued that the current discussion concerning immigration may be overlooking key considerations.

“Immigration has grown in recent years. There are a number of immigrant gateway communities that have grown in the last two decades. Immigration is now a Heartland issue, it’s a Southern issue. It’s no longer just about border communities and New York and San Francisco anymore,” said McKenzie. “Immigration for economic reasons has petered out or even reversed in the wake of the recent recession; without the capability to get a job, out-migration outpaced in-migration following the Great Recession, causing an imbalance.

“Political actions — especially those created in the 1990s — have created weird and unpredicted constructs to the way people move. One, the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996, set up bars for re-entry into the United States for those that have been illegally residing in the country for more than six months, taking away fines for illegal residency and making it more difficult for one to return to the U.S. after returning to his/her origin country to proper process the permanent residence paperwork.”

McKenzie argued that laws, such as the IIRIRA, have contributed to increasing the difficulties immigrants face in seeking permanent residency status or naturalization.

With the Mexican economy improving at a rate superior to the American recovery, many who had sought economic security in the U.S. are returning home, where many have been able to find higher paying jobs that were not available when they left. While the Mexicans and Americans Thinking Together study found that 67.7 percent of all migrants to the U.S. only intended to stay in the country temporarily, a lack of critical services, access to jobs, and legislative and economic discrimination hastened many departures.

The study also found that among the emigrants who participated in the review, 43.3 percent were unable to read in English following their stay in the country; 46.6 percent were unable to write in English; 2.5 percent or less participated in civic activities, such as engaging with a religious organization or joining a sports club; and 46.8 percent reported a significant improvement in their quality of life after they returned to their country of origin.

Figure 1: Rate of increase in English language-deficient populations, from 1990 to 2010. (Data source: Migration Policy Institute:

Since 1990, the largest shifts in immigration patterns have occurred in states such as Georgia, North Carolina, Nevada, Arkansas, Nebraska and Minnesota (see Figure 1). This swing in diversity in these formerly racially-homogeneous states prompted a political backlash that has manifested not just on the federal level with the passing of IIRIRA and the fortifying of the U.S.-Mexican border, but also with the introduction of state- and local-level anti-immigration legislation, such as Arizona’s Senate Bill 1070.

SB 1070, titled “Support Our Law Enforcement and Safe Neighborhoods Act of 2010,” made it a state misdemeanor for an alien over the age of 14 who has been in the U.S. longer than 30 days to not have registration documents in his or her possession at all times. While this reflects federal law — which also recognizes non-possession as a misdemeanor, the fact that it is a state law makes it possible for local law enforcement to stop and arrest someone for the offense.

This, in effect, made immigration enforcement a local priority — as well as a federal priority — in Arizona. The law required local police officers, while participating in a lawful stop, to request registration documents if the officer had reason to suspect the stopped individual was an immigrant residing in the country illegally.

The law also made the act of harboring or assisting those residing in the country illegally a fineable offense in Arizona, which served to put relief groups on notice. Despite being seen as a gross example of racial profiling, the immigration status check provision of the law was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2012 in the case of Arizona v. United States. Similar bills were introduced in Michigan, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island and South Carolina in 2010. While none of these bills passed, nearly 20 states introduced SB 1070-similar bills in 2011, with Alabama, Indiana, Georgia, South Carolina and Utah — all of which either have a Tea Party-affiliated governor or significant Tea Party representation in their state legislatures — successfully passing a version of the law.

Mother Jones found that from 2010 to April 2012, 164 anti-immigration laws passed state legislatures, marking one of the more restrictive periods in immigration legislation in recent memory. These laws impact whether an immigrant can get a driver’s license, under what circumstances a police officer can stop or arrest a suspected immigrant, and what services state or local governments can offer immigrants, among other issues.

There are a number of reasons for the mushrooming of such legislation. McKenzie and Mother Jones have pointed out that during this restrictive period, growth in the private prison industry also expanded. With many states having agreements with private prisons requiring minimum occupancy, some have speculated that many of the legislative and enforcement changes — particularly, among the border states — are, in part, fueled by lobbying from the private prison industry.

Others, however, suspect the influence of “white fear,” or the notion that white Americans are losing majority control of the nation. With the Census Bureau reporting that the U.S. is slated to have a Hispanic majority by 2043, and with four states and the District of Columbia already “majority-minority,” some among the extreme fringe have grown to see current immigration patterns as a threat to the status quo.

Migration and human rights

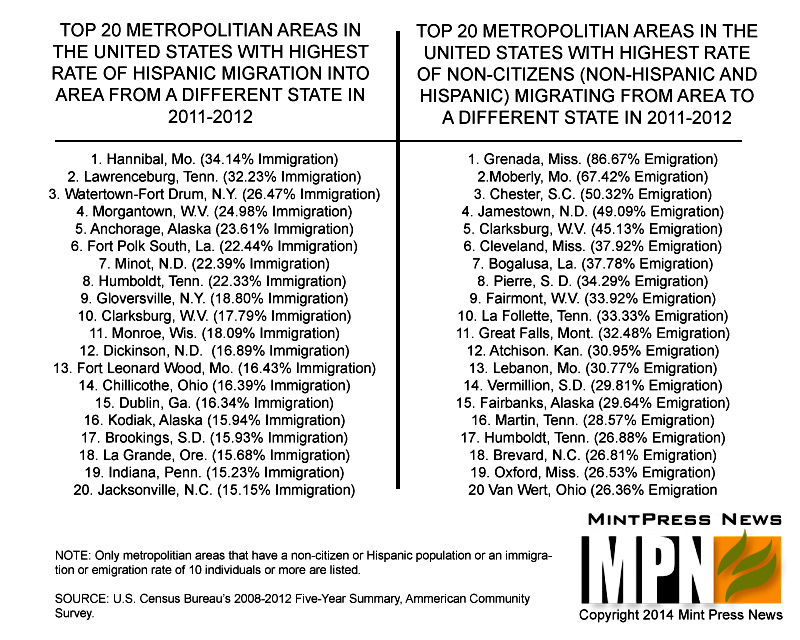

The net result of these laws is best reflected in the migratory flow of non-permanent residents not only from the U.S., but from state to state, as well. “Certainly, there has been a great deal of attention in those communities that have had very high profile anti-immigration legislation,” said McKenzie, of The Advocates for Human Rights. “Out-immigration from these states was well-documented, as were the results of these actions, such as difficulties in completing the harvest, as in the case of Alabama.”

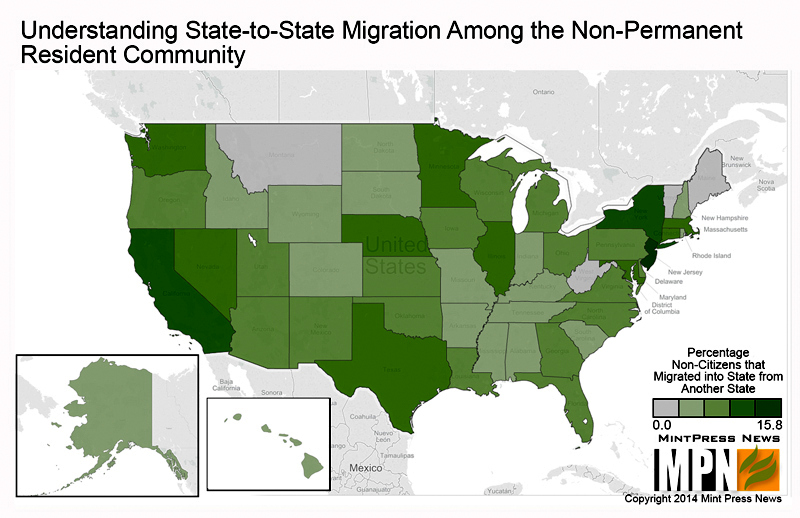

While there have been no comprehensive studies showing how specific laws have affected the movement of non-permanent residents, some conclusions can be drawn from the existing data. The Census Bureau’s American Community Survey data, for example, shows that the communities which show the largest rates of emigration are small Southern communities in states that have passed aggressive anti-immigration legislation (see Figure 3). Similarly, the states that have seen the greatest influx of non-citizens are progressive states, states with healthy economies, or states with significant migrant or Hispanic communities (see Figure 2).

“There is evidence to suggest that racial profiling plays a role in immigration enforcement in some communities the same way race plays a role in law enforcement,” added Rosenblum, of the Migration Policy Institute. This may be due to the fact that the majority of all immigrants residing in the U.S. illegally are Latino, and law enforcement has recently proven a tendency to treat individuals of color more aggressively than individuals of other demographics.

In this lies arguably the core of the immigration argument. As most immigrants residing in the U.S. illegally are Latino, other questions about Latino relations — the question of potential majority status, for example — are becoming intermingled into the immigration argument. While there has been a massive increase in funding for border control and enforcement at the Southwest border, for example, there has been little increase in visa enforcement for the nearly 20 percent of non-Hispanic immigrants who remain in the country on falsified or expired entry documents.

“There is an assumption in this country that a Latino resident of this country who immigrated in or moved in via Puerto Rico is undocumented,” said McKenzie. “It is assumed by some that all Latinos are undocumented. This faulty assumption does not extend to immigrants of other ethnicities. If the white community’s assumption when dealing with deportables is to look for Latinos, this creates a problem with not only the Hispanic community, but with other immigrant groups that may be seeking relief from immigration policies, but may be denied it from this narrow-focused worldview.”