NEW YORK — (Analysis) In late February 2017, Norway hosted an international humanitarian conference on Nigeria and the Lake Chad region in hopes of attracting major donors to fund relief work. As Norway’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Børge Brende explained, “The conference has three aims: to raise awareness about the crisis, to gain more support for humanitarian efforts, and to secure greater political commitment to improve the situation.”

Brende’s concern for the region may be laudable. But no serious examination of the crisis in West Africa can ignore the political and strategic calculus that surrounds the region. As with all conflicts in Africa, questions about resource extraction and neocolonial exploitation abound, with corrupt governments in the region (and their backers in wealthy countries) making the discussion all the more uncomfortable for the most privileged members of global society.

A real discussion of the issue would highlight the questionable connections between regional governments and the development of Boko Haram, the Nigerian terror group that is responsible for much of the havoc being wreaked in the region. It would note the vast energy deposits beneath Lake Chad that evoke an almost Pavlovian response from the leaders of surrounding countries, blinded by the dollar signs in their eyes. It would point out the moves that former colonial powers in Europe are making within the region to enrich themselves and expand their military presence, as well as increase their influence and political power.

In short, the humanitarian crisis around Lake Chad is a symptom of a much larger sickness afflicting the region. We must diagnose the illness in order to treat it, not simply observe its side effects and call for more drugs.

The Shadowy Networks Behind Boko Haram

Some of the statistics on the humanitarian situation around Lake Chad are truly appalling.

According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, there are at least 2.1 million internally displaced people in the region, as well as 7.1 million suffering from hunger. One in every two families need life-saving assistance, according to aid workers. Countless thousands have been killed, injured or otherwise terrorized by Boko Haram and other terror groups. The situation is dire.

So when the UN announced that the conference had raised 672 million dollars to help the people of the region, the news was obviously welcome. With such funds come very serious questions about how the funds will be distributed and who should be responsible for overseeing the distribution process. But determining the real causes of the crisis is perhaps the real million-dollar question.

First and foremost is the question of Boko Haram, its murky origins in Nigerian political conflicts and the ramifications of its actions in the region. While definitive knowledge of the group’s sponsorship remains elusive, there is ample circumstantial evidence to suggest that elements within Nigeria’s government (and potentially other regional governments) have been sponsoring the group from its infancy.

Renowned hostage negotiator and Boko Haram intermediary Dr. Stephen Davis has gone on record as saying that high-ranking elements within the administration of former Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan were involved, including Ali Modu Sheriff, the former governor of Nigeria’s Borno State (the heart of the Boko Haram insurgency) and one of the country’s top military commanders.

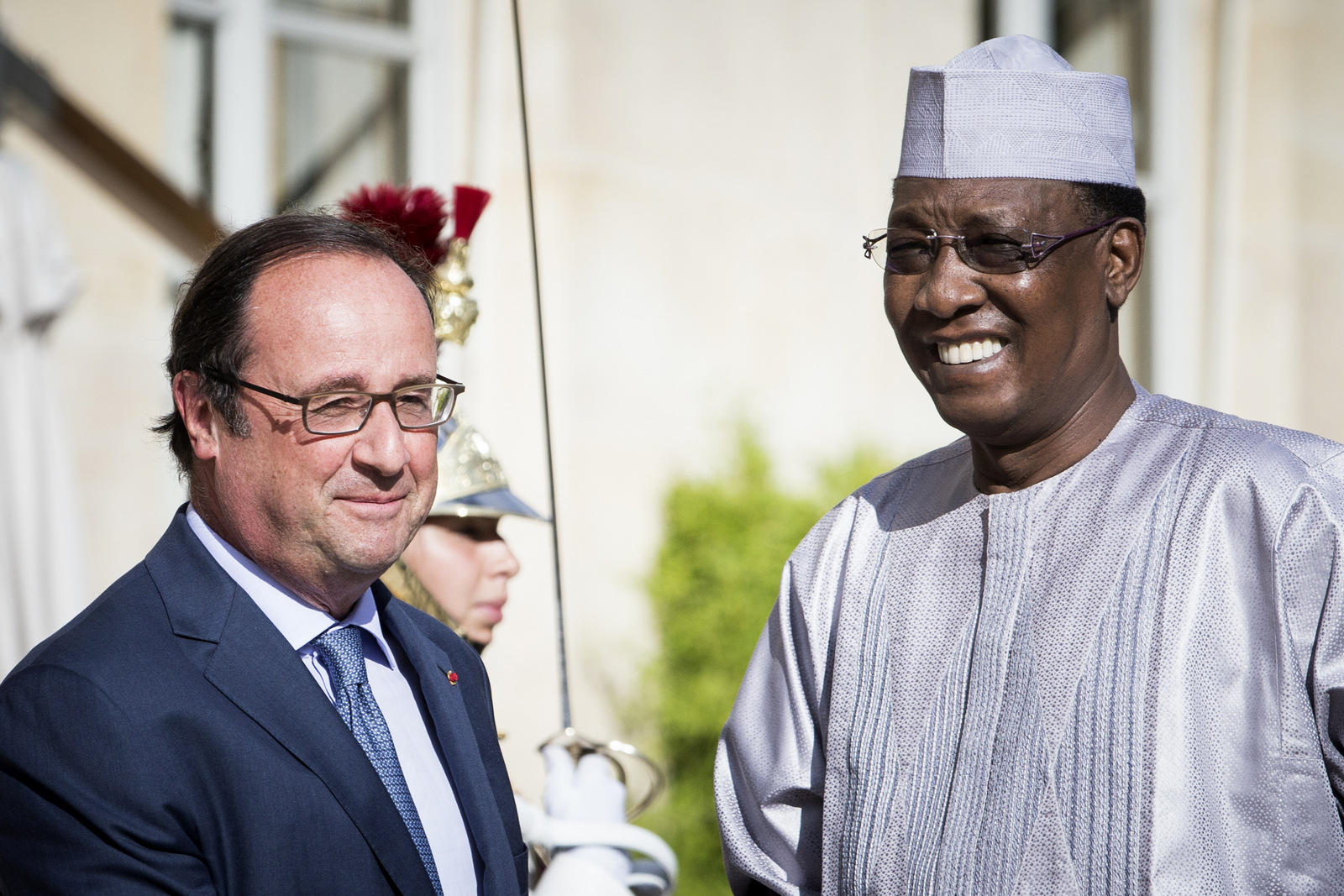

The Jonathan Administration and Nigeria’s military in turn have accused Chad’s government, led by President Idriss Déby, of fueling the unrest for geopolitical and strategic reasons. According to these sources, Déby facilitated the rise of Boko Haram in order to destabilize Nigeria and take advantage of growing energy extraction from the Lake Chad Basin.

While the claim was certainly convenient for a Nigerian government that then was fending off accusations of its own collusion with Boko Haram, it does substantiate a 2011 intelligence memo from field officers in Chad, which noted that “members of Boko Haram sect are sometimes kept in the Abeche region in Chad and trained before being dispersed. This happens usually when Mr. Sheriff visits Abeche.”

Though the details remain murky and may never be fully publicized, even a conservative assessment would note that the domestic politics of Nigeria, as well as regional political infighting, facilitated the emergence of Boko Haram. Indeed, as former President Jonathan’s own presidential panel investigating Boko Haram noted:

“The report traced the origin of private militias in Borno State in particular, of which Boko Haram is an offshoot, to politicians who set them up in the run-up to the 2003 general elections. The militias were allegedly armed and used extensively as political thugs. After the elections and having achieved their primary purpose, the politicians left the militias to their fate since they could not continue funding and keeping them employed. With no visible means of sustenance, some of the militias gravitated towards religious extremism, the type offered by Mohammed Yusuf [leader of Boko Haram].”

From its origins as a collection of gangs used to intimidate people and influence elections to its later development as a cohesive terror organization, Boko Haram has been one of the driving forces of the humanitarian crisis in the region.

Of course, Boko Haram’s rise would have been impossible without the criminal U.S.-NATO war on Libya, which not only toppled the Libyan government, but also led to a tsunami of weapons flowing out of Libya and into the hands of regional terror groups such as al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and the nascent Boko Haram.

In a very direct way, the U.S.-NATO war birthed the violent conflict we see today in the region.

A Humanitarian Crisis and a Resource War

Sadly, most humanitarian crises in the world stem from politics and greed; the human tragedy unfolding in the Lake Chad region is no different. At the heart of the issue is oil.

In recent years, oil discoveries throughout the Lake Chad Basin have transformed how the states of West Africa view their economic future. At the heart of the basin is Lake Chad, surrounded by the countries of Nigeria, Chad, Cameroon and Niger. According to a 2010 assessment from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), the Chad Basin has “estimated mean volumes of 2.32 billion barrels of oil, 14.65 trillion cubic feet of natural gas and 391 million barrels of natural gas liquids.” The potential size of these resources has likely attracted the attention of political and business leaders, both in the region and internationally.

All of the countries surrounding the basin have expressed strong desire in recent years to begin exploiting the energy reserves there. However, until only very recently, Nigeria had been unable to do so due to the Boko Haram insurgency. E&P (Exploration & Production), a publication issued by Hart Energy, noted in March 2014:

“Hopes of stepping up oil exploration in Nigeria’s Lake Chad Basin have been dashed by the brutal attacks of Islamic Boko Haram and the Ansaru sect terrorists in the country’s northeastern region…Between 2011 and 2013, the Nigerian government provided 240 million dollars to facilitate oil and gas exploration activities in the Lake Chad Basin.”

So while Nigeria was forced to put the brakes on its oil exploration and development in the Chad Basin, its neighbors, particularly Chad, continued theirs. Nigeria has jump-started its exploration activities in Lake Chad just in the last few months, presumably thanks to progress that has been made in the fight against Boko Haram.

As Dr. Peregrino Brimah explained in 2014, “The Boko Haram insurgency has conveniently provided Chad, under the government of Idriss Déby, unfettered access to oil under Nigeria’s soils through 3D oil drilling from within its territorial borders, which the country exports.”

It seems that Déby has engaged in siphoning off Nigeria’s oil wealth and exporting it for massive profits for himself and his cronies. But of course, Chad is not alone in this endeavor, as it has company from Cameroon and Niger, both of whom are doing precisely the same thing.

The regional dynamic is key here, as fighting has spilled over the borders into neighboring Cameroon and Niger on numerous occasions. This is precisely the pretext that the U.S. and its European partners are using to become further involved militarily in the region.

Lake Chad and France’s Neocolonial Agenda in West Africa

For the last five hundred years, colonial powers have dominated the political and economic life of Africa. But while formal colonialism may have ended decades ago, the informal dominance and control of Africa continues. This neocolonial control over the continent and its resources is at the root of all conflicts in Africa, including the current crisis in Lake Chad.

Francophone West Africa includes Cameroon, Niger and Chad. This makes France, which continues to be the main trading partner for these countries, into a dominant player in the scramble for Lake Chad. The 2012 coup in Mali and the civil war that subsequently ensued gave the French military the opening it needed to permanently station military forces throughout the region. The ongoing Operation Barkhane has at least 3,000 French troops spread across the Sahel region, including in Niger and Chad.

However, the real question is not whether or not France is right in coming to the defense of its former colonies, but what its real agenda actually is.

Despite its rhetoric of maintaining democracy, stability and the rule of law, France has very self-interested motives. With regard to Boko Haram, Nigeria and the Lake Chad basin, France is the primary beneficiary of the energy extraction taking place there, as its port of Le Havre is the final destination for the unrefined oil. Taken in terms of both actual and potential exports, the area’s vast energy reserves are worth billions. But France’s economic interest in the region does not stop with energy.

France has a keen interest in exploiting lucrative mineral deposits throughout the area, as is evidenced by the fact that the government of French President François Hollande is investing more than half a billion dollars in a new state-owned mining company.

As French industry minister Arnaud Montebourg stated while announcing the creation of the new venture, “Francophone African countries, notably, would like to work with us, rather than do business with foreign multinationals.” Naturally, one should take such a statement with a healthy dose of skepticism as to just how much choice those countries, let alone their citizens, will have in the matter. Not only will France be looking to exploit mineral deposits of lithium and germanium, but also rare earth metals that have become highly lucrative due to significant demand for the metals in the tech manufacturing industry.

Moreover, Montebourg’s use of the phrase “foreign multinationals” is quite revealing. For one thing, it seems that the French political and business elite do not consider themselves to be “foreign” when operating in Francophone countries. The neocolonialism of such a mentality is impossible to ignore.

Secondly, it seems almost self-evident that the “foreign multinationals” to which he is referring are ]Chinese companies (both private and state-owned) that have made tremendous inroads throughout the region in terms of mineral extraction and investment. France is clearly cognizant of a possible turf war between themselves and China over West Africa’s resources.

There are also vast deposits of uranium throughout the region that have piqued France’s interest. As Think Africa Press reported in 2014:

“France currently sources over 75 percent of its electricity from nuclear energy and is dependent on Niger for much of its immediate and future uranium supply. This dependence could grow even further when production at the recently-discovered Imouraren uranium deposit is up and running in 2015. The mine is set to produce 5,000 tonnes of uranium per year and would help make Niger the second-largest uranium producer in the world. Areva, which is 87 percent owned by the French state and holds a majority share in three out of the four uranium mining companies operating in Niger, is funding the new mine.”

Add to this the fact that Nigerian President Mahamadou Issoufou is a former employee of Areva, a company that still maintains a near monopoly over the uranium trade. It should come as no surprise that the main competition for Areva (and France) for this lucrative trade is China, which “already owns a 37-percent stake in Niger’s SOMINA mine and has carried out uranium exploration throughout the country.”

The battle between France and China for control of strategic resources and markets is becoming an increasingly critical part of France’s overall policy in the region. France’s goal is to re-establish economic hegemony in its Francophone sphere of influence, as is evidenced by the French government’s policy paper “A partnership for the future: 15 proposals for a new economic dynamic between Africa and France,” which could be seen as a blueprint for French policy in the area.

This increased emphasis is likely due to the fact that “over the past decade, France’s share of African trade plummeted from 10 to 4.7 percent, while China’s African market share soared to over 16 percent in 2011.” The contours of this proxy war are unmistakably apparent.

The Growing U.S. Military Footprint

Compared to France, the U.S. is waging an even greater geopolitical and strategic proxy war with China over Africa’s resources. While China’s influence on the continent has grown by leaps and bounds, Western countries, especially the U.S., have been left scrambling to shore up their hegemony over the continent. The U.S. has chosen to meet Chinese economic penetration with military occupation, both overtly and covertly.

The U.S. has established a vast network of drone bases in the region, though military officials refuse to describe the facilities as anything more than “temporary staging areas.” But a simple look at the map above, combined with disparate reports in multiple media outlets, paints a much more insidious picture of what the U.S. is doing.

Under the auspices of AFRICOM, the U.S. operates in nearly every significant country on the continent. In Chad, which figures prominently in the Boko Haram narrative, the U.S. has indefinitely stationed military personnel, ostensibly to search for Nigerian schoolgirls who were kidnapped by Boko Haram.

However, the White House’s own press statement reveals a much more far-reaching objective:

“These personnel will support the operation of intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance aircraft for missions over Northern Nigeria and the surrounding area.”

Translation: The U.S. has drones and other surveillance covering the entire Lake Chad Basin.

While the U.S. only acknowledged sending a small contingent of soldiers, the reality is that far more U.S. forces are engaging in Chad in one form or another. This is perhaps best illustrated by the not-so-coincidental fact that Chad played host to AFRICOM’s Flintlock 2015 military exercises “which [took place on] Feb. 16, 2015 in the capital N’Djamena with outstations in Niger, Nigeria, Cameroon and Tunisia, and will [run] through March 9, 2015.”

To summarize, U.S. military personnel led exercises all throughout the region, with specific attention to the Lake Chad Basin countries. But it certainly doesn’t stop there.

The U.S. now operates two critical drone bases in the region, with one base in Cameroon’s city of Garoua and another in the Nigerian city of Agadez. As the Intercept reported:

“’The top MILCON [military construction] project for USAFRICOM is located in Agadez, Niger to construct a C-17 and MQ-9 capable airfield,’ reads a 2015 planning document. ‘RPA presence in NW Africa supports operations against seven [Department of State]-designated foreign terrorist organizations. Moving operations to Agadez aligns persistent ISR to current and emerging threats over Niger and Chad, supports French regionalization and extends range to cover Libya and Nigeria.’”

The strategic value of such bases is perfectly clear. As the Washington Post noted:

“The Predator drones in Niger…give the Pentagon a strategic foothold in West Africa… Niger also borders Libya and Nigeria, which are also struggling to contain armed extremist movements… [Nigerien] President Issoufou Mahamadou said his government invited Washington to send surveillance drones because he was worried that the country might not be able to defend its borders from Islamist fighters based in Mali, Libya or Nigeria… “We welcome the drones,” Mahamadou said… “Our countries are like the blind leading the blind,” he said. “We rely on countries like France and the United States. We need cooperation to ensure our security.”

And here the connection between U.S. military engagement and Boko Haram becomes painfully clear. The U.S. cynically exploits the instability in the region – a direct outgrowth of the U.S.-NATO war against Libya – to further entrench its military.

U.S. Military Empire Expands Elsewhere in Africa

Recent years have seen other countries in sub-Saharan Africa struggling with terrorism and in desperate need of “assistance” from the U.S. While some might recall the January 2016 attack on a luxury hotel in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso’s capital, few know that the U.S. uses the country as a key node in its aerial surveillance and military intelligence network in Africa.

As the Washington Post reported in 2012:

A key hub of the U.S. spying network can be found in Ouagadougou, the…capital of Burkina Faso… Under a classified surveillance program code-named Creek Sand, dozens of U.S. personnel and contractors have come to Ouagadougou in recent years to establish a small air base on the military side of the international airport. The unarmed U.S. spy planes fly hundreds of miles north to Mali, Mauritania and the Sahara.

Of course, these examples only scratch the surface of the vast military and surveillance architecture constructed by the U.S. in Africa over the last decade or so.

With China becoming an increasingly dominant economic force on the continent, the U.S., France and other powers have moved to consolidate their control over both the resources and politics of Africa through militarization. The crisis in Lake Chad is just one of the sad results of these efforts.

It would be incorrect to say that the crisis in Lake Chad is entirely and solely attributable to imperialist intrigue. It must be said that climate change is also playing a huge role, as Lake Chad, once the largest reservoir in the Sahel region of Africa, has lost roughly 80 percent of its total area. The loss of portions of the lake has had a direct negative effect on people’s livelihoods and access to water. This has had the effect of driving desperate young men into the arms of Boko Haram and other criminal groups.

Though the circumstances may be complex, the Lake Chad crisis cannot be fundamentally resolved without addressing the political and geopolitical questions at the heart of it all.

There is a certain dialectical irony in the fact that climate change helps fuel the loss of Lake Chad which, at the very same moment, is being exploited for its oil wealth. There is an almost tragicomic quality to such a reality.

Sadly, it is an all too painful reality for the millions of Africans who live it every day.