NEW YORK — On Monday, over a dozen black and solidarity groups launched an ongoing occupation of New York’s City Hall Park and other public areas in lower Manhattan.

“The only way that we can see an end to police violence is to abolish the police,” Nabil Hassein, an organizer with Millions March NYC, which announced the demonstration and mobilized a coalition of other groups around it, told MintPress News on Tuesday morning.

The demonstration follows a spike in protests after police killings of two black men, Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge and Philando Castile outside St. Paul, Minnesota, as well as the acquittals or dropping of charges against all Baltimore police officers implicated in the death of Freddie Gray last April.

Shortly before City Hall Park’s scheduled closing at midnight, the hundreds of protesters gathered there marched several blocks to West Plaza.

The plaza’s status as a privately-owned public space (POPS), with around-the-clock access guaranteed to the public as a condition for zoning concessions from the city, technically allows its use by demonstrators and other groups at any time.

A similar legal framework allowed Occupy Wall Street protesters to fill Zuccotti Park, another POPS several blocks south, for nearly two months in 2011.

After midnight on Tuesday, with demonstrators gathered in clusters throughout West Plaza, NYPD legal officers wandered through the brick courtyard examining its signs.

Witnesses said police had tried to convince the managers of New York by Gehry, an adjacent residential building that owns the plaza, to file a noise complaint against the demonstration, but failed.

‘We don’t think you can fix a system that isn’t broken’

“A lot of what it’s going to look like is going to depend on the numbers of people who show up, the kind of community engagement and support that we’re able to bring to the park,” Hassein said Tuesday after a smaller number of weary protesters straggled back into City Hall Park at 6 a.m.

Organizers said the event drew particular inspiration from occupations of Homan Square, a secretive facility where the Chicago Police Department allegedly tortured detainees, and Los Angeles City Hall.

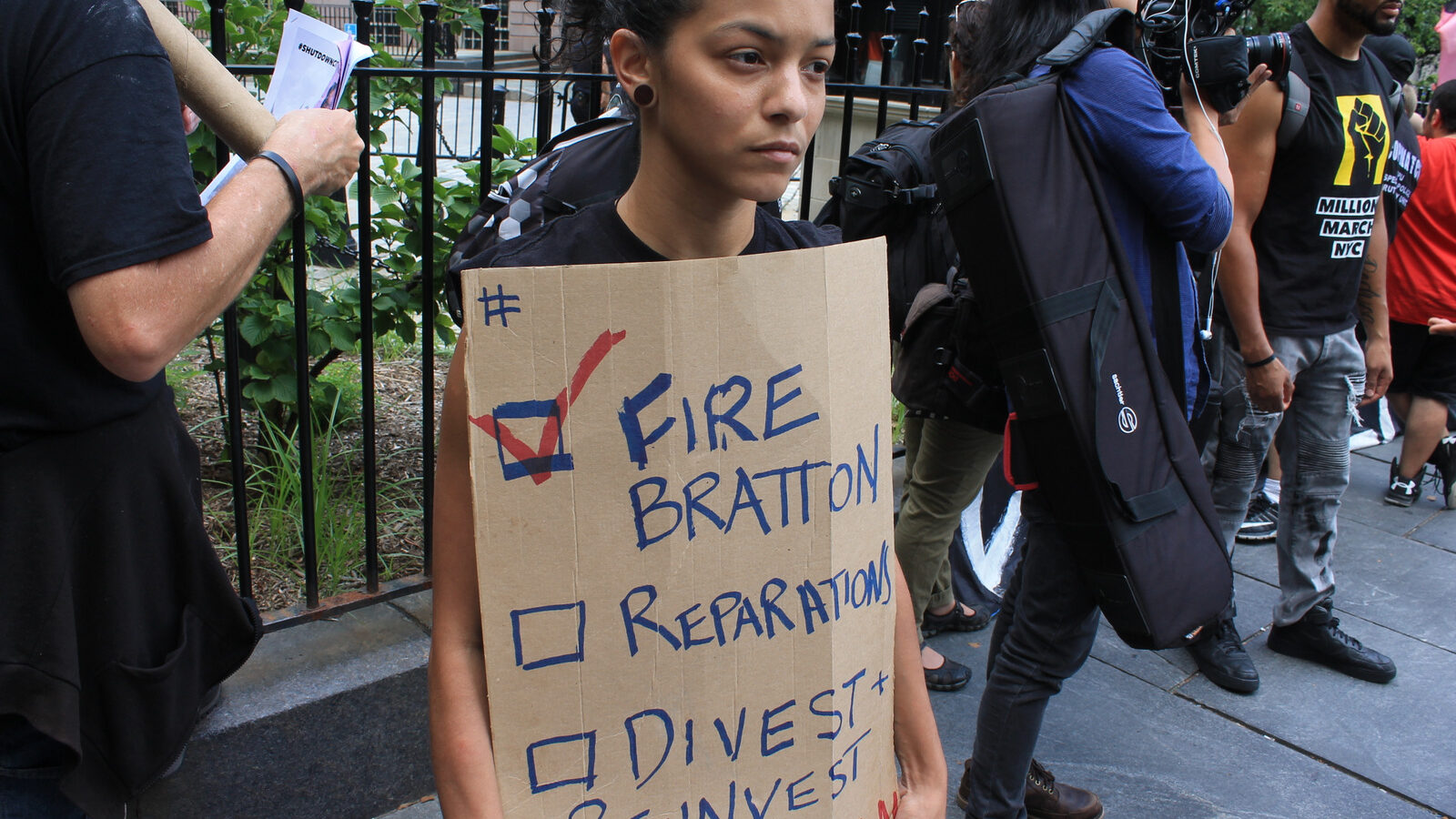

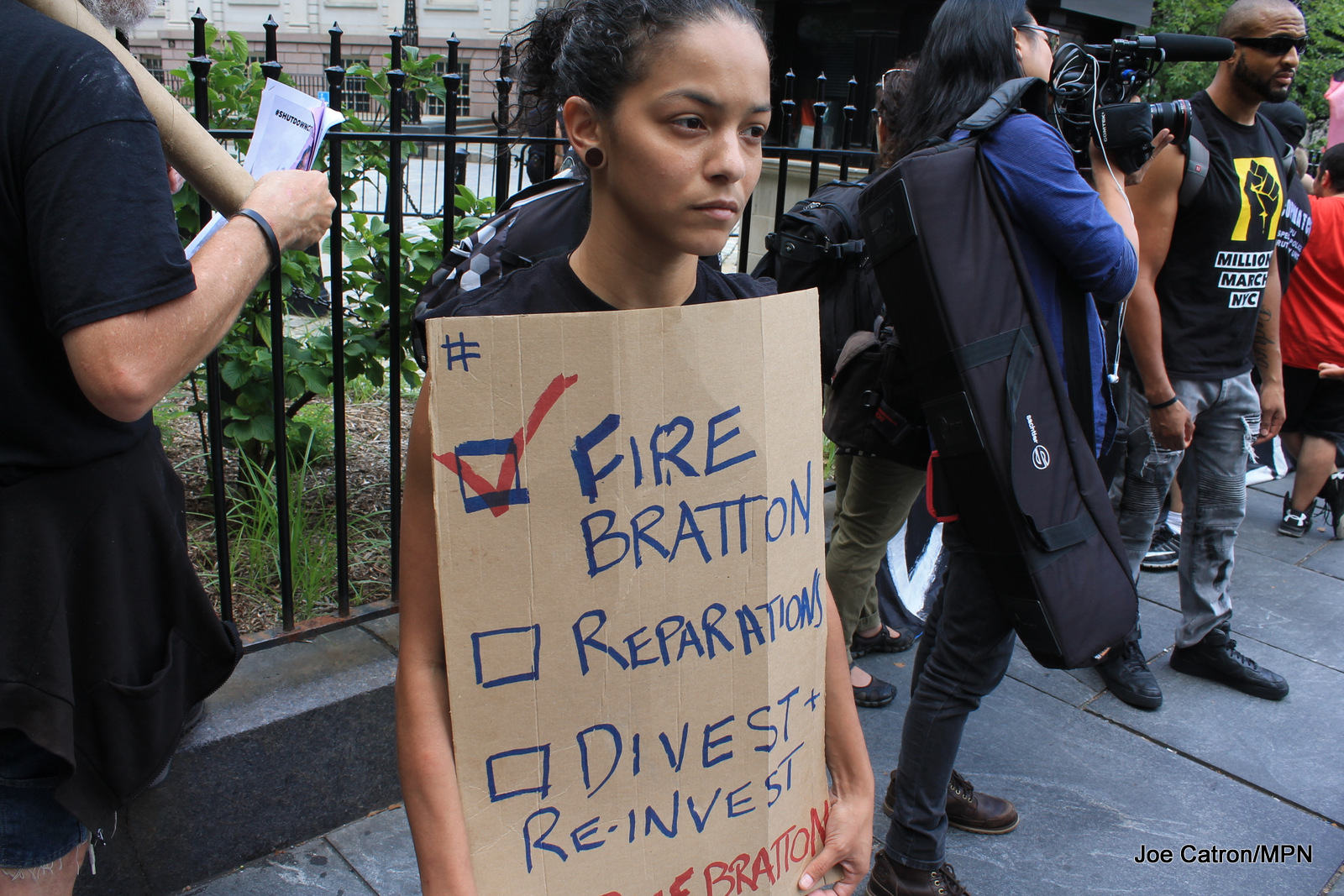

They also say the New York occupation’s demands — that the city defund the NYPD, fire NYPD Commissioner Bill Bratton and end his policy of “broken windows” policing, and pay reparations from the NYPD budget to all survivors and victims of racial police violence — are a conscious escalation in the growing movement’s language.

“We don’t think you can fix a system that isn’t broken,” Hassein said. “Some groups will say things like, ‘We’re not anti-police. We’re just anti-police violence.’ But the fact is that the police are an inherently violent, brutal and racist institution.”

On Tuesday, protesters celebrated an early, if partial, win, as police sources announced Bratton’s abrupt departure from the NYPD to various media.

Hassein added that in the coming days, organizers hoped to expand the gathering with workshops and discussions on alternatives to policing and incarceration, “to envision and build a world without the police, without jails or prisons, to really think through all of the issues – which of course are very difficult and challenging issues – involved with solving intracommunal violence, gender violence, and all these issues in our communities without state intervention.”

‘The movement is focused right now, but there are two different focuses’

Past differences between moderate and more radical activists have often manifested themselves in debates over protest tactics and relations with government officials.

After Millions March NYC organized the demonstration that inspired its name, drawing tens of thousands to the streets of Manhattan in December 2014, Mayor Bill de Blasio inspired months of acrimony among protesters by claiming that members of another group, Justice League NYC, had promised in a closed meeting to inform on demonstrators involved in scuffles with police.

On Monday, a set of “community agreements” posted in City Hall Park and West Plaza warned against any repetition of the episode, saying that “cooperation with or involvement of NYPD or any other law enforcement entity” or “closed-door discussions with politicians regarding #ShutDownCityHallNYC” would be “grounds for automatic removal.”

Meanwhile, the political discourse of abolition, manifested in the event’s demands, signs and chants, seemed to even more dramatically heighten its differences from nonprofit groups with ready access to city officials and cordial ties with police leaders.

“The movement is focused right now, but there are two different focuses,” Colin Ashley, an organizer with the People’s Power Assemblies, told MintPress. “There’s a segment of the movement that is very much dedicated to the idea of reform and what that might mean in terms of the political party system. The other side is seeking the more radical route.”

“There is definitely a division within the movement for black lives, and in other movement spaces, between abolitionist groups and reformist groups,” Hassein added. “And we’re very clear about which side of that division our organization stands on.”

‘This is really some of the most crucial work that’s facing our movements now’

As the New York occupation and similar efforts nationwide continue, circumstances will affect their ultimate outcome, but in ways few can predict, organizers say.

“The political climate is important to the possibilities of the movement,” Ashley said. “What makes things really interesting for Black Lives Matter in this moment is how crazy the election is right now, and who we have running.”

“The radical arm of the movement may have something more to say than reformists. But maybe not. Maybe people are so scared that the middle-centrist route is all folks can imagine.”

But whatever happens in the short term, activists hope their efforts will expand the horizons of what others ultimately see as possible.

“This is necessary when we consider what we know about the police, like the fact that they are descendants of slave patrols and have always existed to repress and terrorize our communities,” Hassein said.

“Bringing them into our communities is never going to address or solve our problems. So despite all of the challenges we face, this is really some of the most crucial work that’s facing our movements now.”