An emerging defense of Joe Biden’s Democratic presidential campaign is that many of his questionable political acts occurred during a “different time.” When it comes to the 1994 “crime bill,” it is excused as a product of a time when the United States was more tolerant of racial injustice than it is today.

Biden wrote the legislation that became the law signed a few months prior to the first midterm election of Clinton’s presidency. It was not an organic response to public concern but a deliberate strategy to appeal to conservative white voters.

Nonetheless, pundits like Josh Marshall of Talking Points Memo, for example, believe progressives are missing some sort of context for Biden’s policy positions and suggests it’s naive to believe they are any cause for concern.

“The [crime] bill was coming just after the peak of the late 20th century crime wave which totally transformed American politics. Though we know now it had just crested, this was not at all clear at the time,” Marshall wrote. “It was also to a great degree meant to counter throw-away-the-key crime politics being pushed by the GOP.”

“If you were alive at the time you’ll remember that much of the 1994 campaign was run on the basis of GOP ads targeting programs like midnight basketball as risible liberal feel-goodism. Even a majority of the Congressional Black Caucus voted for it.”

Positioning the crime bill as a reflexive response to “rising crime rates” is not only an invention but also a subtle way to blame minority communities for bringing punitive and violent policies upon themselves.

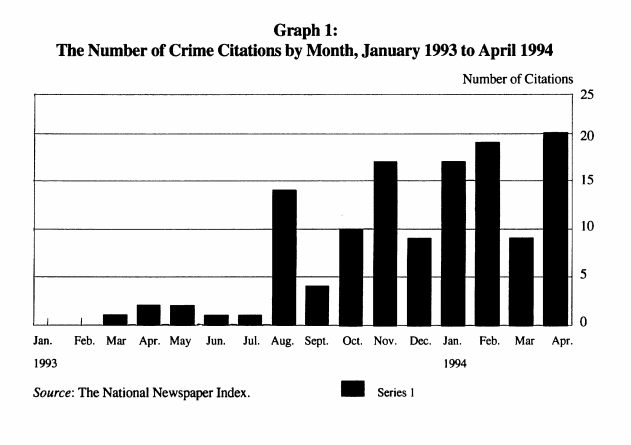

Plus, it seems Marshall’s memory is not as reliable as he thinks. As documented by Tony G. Poveda in 1994 for the quarterly journal Social Justice, the public was relatively uninterested in the subject of crime until late 1993, when Clinton Democrats realized there was value in trying to steal the crime issue from Republicans.

Clinton did not make crime a paramount issue during his 1992 campaign. It made a small appearance in a policy agenda that mainly focused on jobs and the economy.

Poveda analyzed news archives from 1993 and 1994 and found mentions of crime issues were relatively minor until the White House announced plans around community policing and gun violence in August 1993.

In the fall of 1993, public opinion polls showed crime quickly rising as a public concern and eventually overtaking jobs and the economy as the country’s most important problem (Ingwerson, 1993: 3; “Washington Wire,” 1994: 1). By January and February of 1994, it appeared that the Clinton administration was having some success in “stealing” the crime issue from the Republicans. One Washington Post ABC News poll, for example, which questioned the public regarding their confidence in each political party’s ability to handle the country’s problems, gave Democrats a 39% to 32% advantage over the Republicans in dealing with the crime problem (Balz, 1994: 13). Although President Clinton came late to the crime issue, it was soon apparent that its political value lay in the possibility of co-opting a traditional Republican issue.

The White House pursued an ill-defined and amorphous crime agenda from the outset, unable to articulate particular policy preferences as the administration called for tougher approaches to “predators.” As the crime bill developed, the president ignored strong criticism and suppressed reports from his own Justice Department, which called the proposals into question.

Attorney General Janet Reno eventually supported the crime bill under pressure from the White House, but she was initially a staunch opponent of its measures to expand police forces, the death penalty, and mandatory minimum sentencing.

Still, Marshall believes the right-wing politics of the crime bill can be forgiven due to the eventual support of the Congressional Black Caucus.

Not only does this disregard the context of that support—namely, the pressure and trade-offs black Democrats faced to not make their president look weak, but how black Democrats voted in the 1990s is no rational basis for dismissing Biden’s record.

It is indisputable that Joe Biden took a leading role in this cynical Democratic strategy. In doing so, he helped redefine the party’s traditional ideological boundaries on issues of crime and drag it further to the right.

Within this context, opponents of the “crime bill” spoke loudly against it, including prominent national civil rights groups like the NAACP and ACLU.

As it became law, the New York Times ran an article titled, “Experts Doubt Effectiveness Of Crime Bill.” It described the legislation as “a sprawling array of programs, many of them untested, that taken together have little overall coherence.” They cited multiple experts who questioned the overall tough-on-crime approach, as well as specific policy provisions.

“Whether the measure signed today provides the tools to reduce crime or is merely a flimsy bauble to dangle before voters is something still being debated,” the Times observed.

If context is necessary for discussing Biden’s choices, then it is worth examining the compromises forced by Democratic leadership adopting a southern strategy. And, if progressive support for the crime bill, then the pressure under which other progressives were made to support the president’s policy proposals must be recalled too.

For example, the Violence Against Women Act was included in the “crime bill,” leading senators and representatives, like Bernie Sanders, to back it.

Biden’s brash dog-whistling rhetoric in 1993 distinguished him. “We have predators on our streets that society has in fact, in part because of its neglect, created.” He suggested they were “beyond the pale,” and we had no choice but to “take them out of society.”

“It doesn’t matter whether or not they had no background that enabled them to become socialized into the fabric of society. It doesn’t matter whether or not they’re the victims of society. The end result is they’re about to knock my mother on the head with a lead pipe, shoot my sister, beat up my wife, take on my sons,” Biden stated.

In contrast, Sanders declared in a floor speech in April 1994, “A society which neglects, which oppresses and which disdains a very significant part of its population—which leaves them hungry, impoverished, unemployed, uneducated, and utterly without hope, will, through cause and effect, create a population, which is violent, and a society, which is crime-ridden. This is the case in America, and it is the case in countries throughout the world.”

Biden defended the crime bill as recently as 2016, only to reverse his position in January 2019, a few months before launching his latest attempt at the White House.

For pundits who believe 1990s Joe Biden was an aberration, let’s examine Biden’s behavior around the 2008 campaign, over a decade later.

When Biden was initially considered a potential vice presidential pick for President Barack Obama’s administration, the progressive blog Jack and Jill Politics examined his “history of racially insensitive and offensive remarks” pulling from comments he made in 2006 and 2007.

“I mean, you got the first mainstream African American who is articulate and bright and clean and a nice-looking guy,” Biden said of Obama in January 2007.

In October of that year, Biden argued Iowa schools performed better than those in Washington, D.C.“There’s less than one percent of the population of Iowa that is African American. There is probably less than four of five percent that are minorities. What is in Washington? So, look, it goes back to what you start off with, what you’re dealing with.”

“When you have children coming from dysfunctional homes, when you have children coming from homes where there’s no books, where the mother from the time they’re born doesn’t talk to them as opposed to the mother in Iowa who’s sitting out there and talks to them, the kid starts out with a 300 word larger vocabulary at age three,” Biden declared. “Half this education gap exists before the kid steps foot in the classroom.”

The year before, as Biden bragged about his relationship with the Indian community, he said, “You cannot go to a 7-11 or Dunkin Donuts unless you have a slight Indian Accent. Oh, I’m not joking!”

Biden went on Fox News and said Delaware was “a slave state that fought beside the North. That’s only because we couldn’t figure out how to get to the South. There were a couple of states in the way.”

Talking Points Memo itself hosts a video featuring Biden during a presidential debate that campaign cycle, when he said, “I spent last summer going through the black sections of my town holding rallies in parks trying to get black men to understand it’s not unmanly to wear a condom. Getting women to understand they can say no. Getting people in the position where testing matters.”

“I got tested for AIDS. I know Barack [Obama] got tested for AIDS. There’s no shame in being tested for AIDS.”

Invoking “different times” as a defense of candidates with long careers, who promoted racist or bigoted policies, also deserves to be challenged.

The “different times” defense primarily benefits the privileged. It erases the voices of dissidents while absolving mostly white men of “not knowing any better.” It disappears the decision makers behind exercises of state violence, as well as the role of politicians and the media in stoking the hatred and resentment which enables violence.

In fact, the tactic is not unique to the political moment. Pundits used the excuse to defend the decision to invade Iraq or to downplay the wave of anti-Muslim violence following the September 11th attacks.

Perhaps, one of the biggest differences between those times and today is that anti-racist groups or movements for justice and equality are stronger. They are more visible than ever, and their growing influence gives them the ability to challenge society’s general recollections of how racist and bigoted agendas inflicted trauma. They are also able to call out individual politicians who have not atoned for their history of support for these toxic policies.

Today’s centrist liberals wish to exclude the voices of those impacted by these policies just like they did in the 1990s. Maybe the times are not so different after all.

Feature photo | Former Vice President and Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden speaks during a rally, April 30, 2019, in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Charlie Neibergall | AP

Kevin Gosztola is managing editor of Shadowproof Press. He also produces and co-hosts the weekly podcast, “Unauthorized Disclosure.“

Brian Sonenstein is the publishing editor at Shadowproof and a columnist at Prison Protest.

Source | Shadowproof