LONDON — Dubbed “the fountainhead of Islamist terrorism” by Yousaf Butt, senior advisor to the British American Security Information Council, Saudi Arabia has found itself at the center of many controversies over the past year.

From inspiring and supporting the Wahhabi ideology of ISIS to fuelling sectarianism in the Middle East to better assert its all-Sunni state agenda in a bid to monopolize the oil market, the kingdom appears to have enacted a disturbing religious agenda that harkens back to the 1930s, when white supremacists thought to cleanse their genetic patrimoine to give rise to a purer, more “worthy” racial legacy.

Though Riyadh didn’t exactly come out screaming that all Shiite Muslims and other religious minorities should be disappeared, Hasan Sufyani, a leading political analyst at the Sana’a Institute for Arabic Studies, argues that the kingdom’s henchmen are laying the groundwork for a religious cleansing movement.

“Religious minorities in the Middle East have never been under such aggravated threat. Christians in Iraq and Syria have been massacred en masse, Shia Muslims have been persecuted, their faith belittled and chastised by radicals on Riyadh’s payroll,” Sufyani told MintPress News.

“Worse still,” he added, “the kingdom has simultaneously funded a grand regional anti-Shia political campaign to better ostracize its political and religious representants while the world’s communities have become accustomed to such public flagellation.”

But if religion has been propelled to the forefront of this engineered divide, the root cause of Saudi Arabia’s ire remains tied up to geo-economics — namely, control over oil and gas resources. Religion and religious legitimacy are but a smokescreen to mask the kingdom’s agenda and create a rallying point for the Sunni Islamic world.

Shiite communities tend to be concentrated in oil-rich areas, though this is by no means deliberate. The Times of India reported in a 2006 analysis of sectarian strife in Iraq: “The biggest oilfields in the country are in the Shia south, and the rest are in the northern Kurdish region. There is no oil in the Sunni triangle in the middle of the country.”

John Whyman, a researcher on radical movements for the Sana’a Institute, says that while patronage and political pressure have obscured Riyadh’s religious cleansing agenda from the media eye, evidence of its existence has become too overwhelming to ignore. He explained:

“Although of course Riyadh has covered its tracks by implementing different policies to different countries in the Middle East, the underlying theme has always been to assert Wahhabism as the only viable religious model. 2011 events precipitated the Wahhabization of the region from covert to openly violent.”

Indeed, Riyadh’s ominous shadow towers over regional horrors, from Lebanon’s sectarian tinderbox, to Bahrain’s aggressive denationalization campaign against Shiite Bahrainis, and from Iraq’s Shia and Christian mass executions to the systematic targeting of Yemen’s Zaidi communities. Riyadh’s place in these atrocities is a reality many have either chosen to ignore or have been too blind to see.

To preserve its regional hegemony and sit at Big Oil’s corporate table, the kingdom has already proven there is nothing it won’t do — especially if it means preventing the rise of an Iran-induced, Shiite-led insurrection movement throughout the Arabian Peninsula and across the Shiite Crescent, where the majority of the Gulf region’s oil fields lie. To control the oil, Saudi Arabia is provoking the Sunni- Shiite narrative to play their economic interests.

A dangerous legacy, a sectarian-based dogma

An absolute theocracy based on the most radical and reactionary interpretation of Islam, Saudi Arabia’s Wahhabi have spearheaded a broad religious reinvention of the Middle East since the 18th century, hoping to manifest the founder’s calls for a grand religious cleansing of the Islamic world.

Imperial Britain — and later, the U.S., too — played a critical role in supporting the radical regime. Exploited by the Crown to serve as a weapon against both the Ottoman and Persian empires, Wahhabism was meant as a weapon of mass destabilization and socio-political fracture.

“The Globalists have had a hand in shaping and financing all the terrorist organizations of the twentieth century, including the Muslim Brotherhood of Egypt, Hamas of Palestine and the Afghan Mujahideen. But the history of their duplicity dates farther back still, to the 18th Century, when British Freemasons created the Wahhabi sect of Saudi Arabia itself, to further their imperialistic objectives,” David Livingstone, a Canadian historian and author, wrote in 2006, referencing a 2002 article by Peter Goodgame.

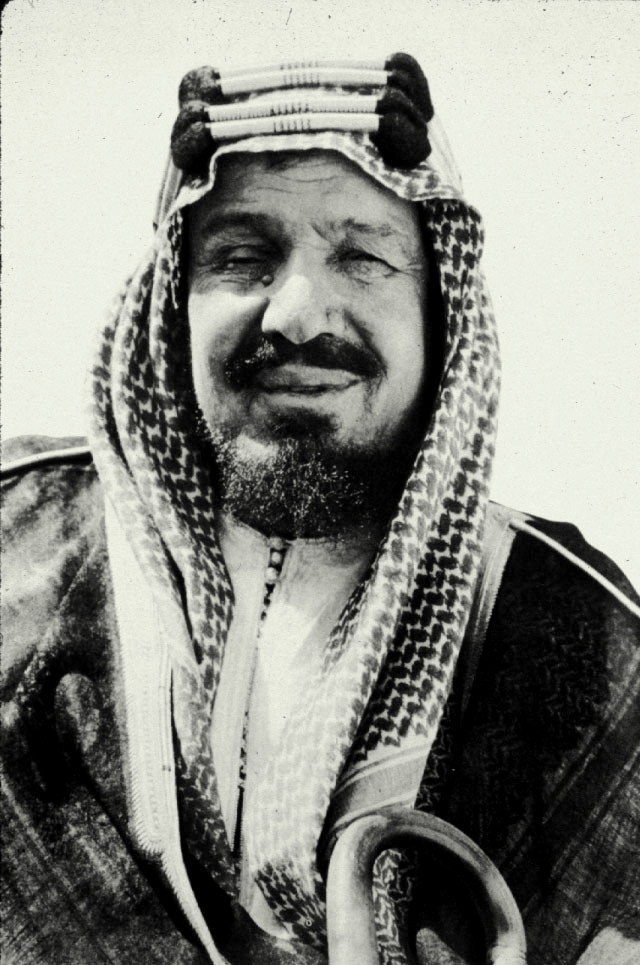

One dominant strand of the Saudi identity pertains directly to the founder of Wahhabism, Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, and how his radical, exclusionist puritanism was used by Ibn Saud, the founder of the House of Saud, to forcibly unite the Hijaz (ancient name of Saudi Arabia). While the latter was then no more than a minor leader among many continually sparring and raiding Bedouin tribes in the baking and desperately poor deserts of the Nejd, the House of Saud’s adherence to Wahhabism gave rise to a radical Wahhabist empire in the Middle East.

A few generations later, Wahhabism would come to rise a religious hegemonic powerhouse rooted in Al Saud’s immense oil wealth, one which has yet to be surpassed since backed by western powers.

“Ultimately, the profusion of Rothschild financed petrodollars in the coffers of the Saudi family has made it possible for them to propagandize their bastardized version of Islam to other parts of the world, most notably to America, where they purportedly subsidize up to 80 percent of the mosques in the country, a version of Islam that substitutes political awareness for dogmatic insistence on ritualistic fanaticism.”

As explained by Dr. John Andrew Morrow, the director of the Covenants Initiative, one of the tenets of the Wahhabi doctrine has inspired the concept of takfirism, the legal killing of all those deemed to be in a state of apostasy.

“Abd al-Wahhab denounced all Muslims in opposition to its ascetic and reductive interpretation of the Islamic Scriptures, arguing that their deaths were not only permissible but desirable, should Islam be reclaimed pure,” Morrow told MintPress.

The founder of Wahhabism held that no “real” Muslims should ever honor the dead, saints or angels. Such sentiments, he argued, detracted from the complete subservience one must feel toward God and only God.

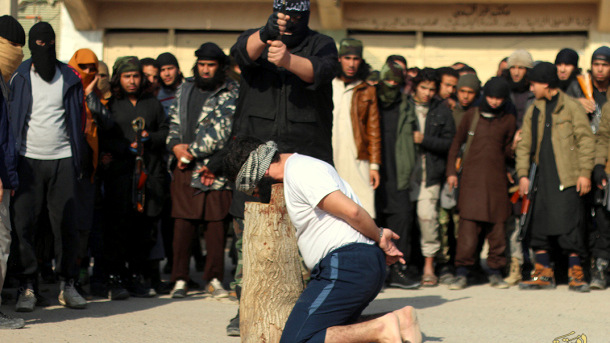

Those who would not conform should be killed, their wives and daughters violated, and their possessions confiscated, Abd al-Wahhab advised, encapsulating in one stroke of the pen ISIS’s morbid agenda against all religious communities in the Middle East.

The list of apostates meriting death included Shiites, Sufis and other Muslim denominations, which Abd al-Wahhab labelled as being inherently un-Islamic, and thus worthy of punishment.

His words and teachings have inspired militants to carve a path of blood and suffering into the Middle East for several centuries. Osman Ibn Bishr Najdi, the historian of the first Saudi state, diligently recorded how Ibn Saud, the forefather of the House of Saud, committed a massacre in Karbala in 1801. He proudly recalled: “We took Karbala and slaughtered and took its people (as slaves), then praise be to Allah, Lord of the Worlds, and we do not apologize for that and say: And to the unbelievers: the same treatment.”

In his 2001 book, “Rise and Fall of the Hashimite Kingdom of Arabia,” Joshua Teitelbaum recalls how in 1803, Ibn Saud raided the holy city of Medina before entering Mecca as a conqueror. He detailed how Islam’s holiest city surrendered under the impact of terror and panic and how in both occasions Wahhabis demolished historical monuments as well as the tombs and shrines locals held in veneration, laying waste Arabia’s religious heritage on account of bigotry.

Today, ISIS is running an identical campaign of destruction and murderous raids. Late last month, ISIS uploaded images onto social media that claim to document the annihilation of Palmyra temple, a Syrian archaeological treasure. The Guardian reported that the photos “showed the temple reduced to a pile of rocks.” One photo caption provided by ISIS read: “The complete destruction of the pagan Baal Shamin temple.”

Time magazine ran an article in February raising concern that ISIS had committed genocide against Iraq’s minorities, underlining both the terror group’s religious agenda and the founding principles of Wahhabism.

A eugenics agenda

William Spencer, executive director of the Institute of International Law and Human Rights, told reporters earlier this year that, “While military action against ISIS dominates the headlines, to date there has been no serious effort to bring the perpetrators of crimes against minorities to justice.”

He added: “Minorities were first caught by wholesale discrimination and violence well before the arrival of ISIS. Now they face a new threat to their existence from ISIS attacks.”

Those minorities are invariably the same: Yazidis, Christians, Alawite Muslims, Shiite Muslims, Sufi Muslims and even Sunni Muslims are caught rejecting Wahhabism.

ISIS’ religious cleansing agenda has been well-documented, if not not directly confronted. “ISIS should immediately halt its vicious campaign against minorities in and around Mosul,” Sarah Leah Whitson, Middle East director at Human Rights Watch, said in July. “Being a Turkman, a Shabak, a Yazidi, or a Christian in ISIS territory can cost you your livelihood, your liberty, or even your life.”

Incensed by world leaders’ apathy before the rising threat of theo-fascism and Wahhabi-led religious cleansing, Dr. John Morrow warned that unless action is taken soon, the world will witness yet another Holocaust at the hands of yet another Nazi Germany.

“The world cries when the Buddhas of Bamiyan are destroyed. The world cries when ancient monasteries and churches are destroyed in Syria and Iraq. The world cries when World Heritage sites are destroyed throughout the Levant,” Morrow told MintPress. “However, the world remains silent, in a stupor of apathy and hypocrisy, when the Wahhabi Najdis carry their openly sectarian and ethnic agenda against religious minorities across the region.”

“The world cries when the Buddhas of Bamiyan are destroyed. The world cries when ancient monasteries and churches are destroyed in Syria and Iraq. The world cries when World Heritage sites are destroyed throughout the Levant,” Morrow told MintPress. “However, the world remains silent, in a stupor of apathy and hypocrisy, when the Wahhabi Najdis carry their openly sectarian and ethnic agenda against religious minorities across the region.”

He added: “ISIS and, through ISIS, Saudi Arabia has declared war on religious pluralism to impose its own dogmatic and bigoted interpretation of Islam in the Middle East. The real crime against humanity here is being blind and deaf to it.”

Edwin Black, author of “War Against the Weak: Eugenics and America’s Campaign to Create a Master Race,” defines eugenics as a racist pseudoscience determined to wipe away all human beings deemed “unfit,” and preserve only those who conformed. Under the Third Reich, for example, the Nordic stereotype dominated the narrative.

Black wrote:

“Eugenics would have been so much bizarre parlor talk had it not been for extensive financing by corporate philanthropies, specifically the Carnegie Institution, the Rockefeller Foundation and the Harriman railroad fortune. They were all in league with some of America’s most respected scientists hailing from such prestigious universities as Stanford, Yale, Harvard, and Princeton. These academicians espoused race theory and race science, and then faked and twisted data to serve eugenics’ racist aims.”

And though Wahhabism does not ambition to recreate a “pure race,” it seeks nevertheless to assert a “pure religion” — its puritanically radical interpretation of Islam.

If, as Black noted, money and power saw fit in the early 20th century to elevate eugenics from a concept to a philosophy and a movement, is it so difficult to imagine that fascism morphed into a new expression of hate?

After all, both eugenists and Wahhabis follow the same elitist philosophy of cleansing, the former based on racial superiority, the latter sectarianism.

But where ISIS’ agenda has been undeniably bloody and openly sectarian, what of the rest of the region? How has Saudi Arabia’s “plan” manifested there?

Saudi Arabia’s eugenist footprint

Last month, the Red Cross joined human rights groups in denouncing Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen, speaking of the horrors the kingdom would have likely prefered to keep out of the media.

Peter Maurer, the head of the international Red Cross, told reporters he had seldom witnessed such a degree of devastation. In an interview with The Associated Press, Maurer said: “The images I have from Sanaa and Aden remind of what I have seen in Syria. … So Yemen after five months looks like Syria after five years.”

He also noted: “The firepower with which this war is fought on the ground and in the air is causing more suffering than in other societies, which are stronger and where infrastructures are better off and people are wealthier and have reserves and can escape.”

While the destruction of Yemen has been systematically violent, civilian deaths appear to have been premeditated, especially in northern Yemen, where the majority of the population follows Zaidi Islam, a branch of Shiite Islam.

According to official UNICEF tallies, as of July 15, “Close to 2,800 people have been killed and almost 13,000 people injured (including 279 children killed and 402 injured, respectively). An estimated 1 million people have been internally displaced (an increase of 122 percent since the crisis began), and some 400,000 people have sought protection in neighboring countries.”

Touching upon the kingdom’s pattern of killing, Ravina Shamdasani, spokesperson for the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, told reporters in Geneva on May 5: “We reiterate that all suspected violations of international human rights law and humanitarian law during the conflict should be investigated, and that the intentional targeting of civilians not taking direct part in the hostilities should be immediately stopped.”

While Yemen’s death toll is horrifying in itself, it does not fully speak to the intent behind the war crimes. And though Saudi officials are unlikely to “come clean” about their sectarian motives, Saudi Arabia’s ambassador to the United States, Adel Al-Jubeir, revealed an interesting feature of the kingdom’s war in Yemen when he declared in an interview in April, “This campaign is having a huge impact in Yemen and it is not over yet. For us failure is not an option. We will destroy the Houthis if they do not come to reason.”

Al-Jubeir continued, asserting:

“We do not look at this [war] as Sunni versus Shia. We look at this as an armed militia group that is radical, that operates a military outside the legitimate government; that is now in possession of ballistic missiles and an air force that represents a threat to Yemen, to Yemen’s people, to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and to the region. This is something we cannot tolerate.”

Despite the ambassador’s insistence that it’s not a sectarian conflict, Riyadh’s insistence on pummeling northern Yemen demonstrates otherwise.

Meanwhile, in Bahrain, Wahhabism is operating under a new cover: denationalization.

In comments to Foreign Policy last month, Saeed Al-Shehabi, a Bahraini doctor and activist who was made stateless in 2012, explained:

“The regime [Al Khalifa] is running out of options. It has tortured people, starved thousands to death, openly killed hundreds of people in the street, and yet Bahrainis are still adamant on achieving change. … Revoking citizenship is just yet another tool to scare people and deter them from asking for their rights.”

Although the trend has been documented at length by rights groups such as European-Bahraini Organisation for Human Rights, Bahrain has encountered no political pressure from its Western partners.

Natasha Bowler writes in her report for Foreign Policy:

“Most people made stateless in Bahrain are from the Shiite majority, whose members often find themselves protesting systematic discrimination at the hands of the government. Despite making up two-thirds of the population, the Shiites occupy virtually no jobs in the army, the government, the judiciary, or other top positions. Because the Sunni regime is fearful that the Shiites will one day overthrow it, it continues to search for ways to suppress them.”

Riyadh’s anti-Shiite, anti-religious pluralism throughout the Middle East has undeniably directed the narrative, pitting communities against each other, justifying heinous abuses and sectarian policies.

In his 2013 book, “Sectarian Gulf,” Toby Matthiesen warns that while the so-called “Shia threat” has become a catchall response to demands for democratic reform and accountability on the Arabian Peninsula and to a greater extent the Middle East, this strategy risks tearing the region’s social fabric and thus facilitating the “rise of transnational Islamist networks.”

Worse, if left unchecked Saudi Arabia’s religious cleansing movement could lead to the institutionalization of sectarianism on a global level. It might also be interpreted as tacit approval of ISIS’ crimes against religious minorities.

As it stands, Saudi Arabia is sponsoring a wide, dangerous policy of religious cleansing under the false pretense of opposing the rise of Iran, the cradle of Shiite Islam, when really it is working to establish an empire to its dogmatic image.