Long-term Republican Sen. Thad Cochran defied popular thinking in June by defeating his Tea Party primary challenger Chris McDaniel in a runoff. Part of Cochran’s success can be attributed to 17 percent more voters turning up to polls for the runoff than for the primary.

The other factor contributing to Cochran’s win was his exploitation of Mississippi’s open primaries law. The Cochran campaign explicitly encouraged the state’s black Democrats to participate in the Republican Senate primary runoff. According to county data analyzed by FiveThirtyEight, this unconventional campaigning accounted for the veteran senator’s 51 percent to 49 percent margin of victory.

Mississippi is home to the country’s highest concentration of blacks by percentage of population. The state also has the largest number of black elected officials. However, black enfranchisement in Mississippi politics is limited to local or regional representation; to date, Mississippi has not had a black official who was elected statewide since Blanche Kelso Bruce was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1874.

This lack of black political engagement on the state level is due to disenfranchisement techniques, such as gerrymandering and the open primary — which appeared in 1975 to allow for black Democratic candidates to be quickly defeated in a primary by an influx of white Republican voters. In the past, many in the black community speculated that black participation in Mississippi politics would be limited to local affairs and the state Legislature. However, the success of Cochran’s primary strategy suggests that Mississippi’s black Democrats can play a role in state- and federal-level politics, even if that role is limited to being the spoiler.

With many analysts now arguing that the GOP can no longer win the White House solely on the strength of the white vote, the changing political composition of the South — long held as an essential component of the Republicans’ national voter base — has become relevant. With a shrinking white voter base and with Democrats claiming significant majorities among Hispanics and blacks in the last two presidential cycles, the South may reflect how the American political environment is changing.

The South currently has two of the country’s four non-white governors — Nikki Haley of South Carolina and Bobby Jindal of Louisiana, both of whom claim Indian heritage. The largest concentration of minority representatives and senators to Congress also comes from the South, including familiar names such as Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida and Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas.

While such political diversity would have been unthinkable in the South a decade ago, and while it may simply be the sum effort of a Republican Party desperate to keep up with the Democrats in regards to minority outreach, this situation begs several hard questions: Does the “Southern Strategy” still exist, and if so, what does its future look like? How will the influx of Hispanic voters into the South change the political landscape? What does all of this mean for the nation as a whole?

Understanding the South

One way to demonstrate exactly what is going on in the South is to look at the shift in political alignment for registered voters (see Figure 1). While the voting populace typically tends to move away from the president’s party, the Southern states have shown, on average, a slower gain in the percentage of voters who report leaning Republican.

Historic numbers of black voters in the South turned out at polls for President Obama in 2008 and 2012, noted Jay Parmley, executive director of South Forward, a federal candidate PAC aimed toward promoting a Democratic South.

“This shows a significant potential for African-Americans to significantly shape and affect Southern politics, giving the Democrats a real chance to win in these places,” Parmley told MintPress News.

He added that while Obama did not win Mississippi, Georgia or Alabama, he did poll competitively there.

“This suggests that — while not necessary making the states competitive yet — the African-American voters in these states are starting to appreciate their own worth and are realizing that turning out to vote can be productive.”

Figure 1: Shifts in Republican Growth by State, 2008-2013.

Despite no significant campaigning in the South, Obama took Virginia and Florida in 2012, just missed North Carolina, posted the best result in Georgia for a Democrat since Jimmy Carter and grabbed approximately 44 percent of the vote in both South Carolina and Mississippi. This marked a political shift for the South. For states adjoining the Mississippi River, the expanded political advocacy of the black community — in conjunction with a growing number of Democratic Hispanic voters — is causing a growing gap between white and non-white voters in these states. For example, while nearly 90 percent of white voters in Mississippi voted for Mitt Romney in 2012, about 96 percent of black voters in the state voted for Obama.

However, a new coalition is forming in the Atlantic Southern states. Growing Hispanic and black populations, combined with local white progressives and liberals who have moved into the commercially-developing South from other parts of the country, have created a new political sensibility that is meeting the entrenched Republican Party in enthusiasm, size and available resources.

“This coalition is not just a factor of numbers,” Parmley said. “Just because someone is Hispanic doesn’t mean that he will vote Democrat or would register to vote. Just because someone is black doesn’t mean he is automatically ready to vote for the next Barack Obama. This newly-formed coalition requires work; it requires feet on the ground, persistent outreach and continuing educating the voters about their options.”

With the black population growing faster than the white population in every Southern state but Louisiana, and with the Hispanic community projected to be the majority ethnic group in the United States by 2043, questions about when and if the Republican Party can accept the changing face of the South remain unanswered.

The “Southern Strategy”

In 2005, then-Republican National Committee Chairman Ken Mehlman apologized to the NAACP for the “Southern Strategy,” a ploy by the Richard Nixon campaign which became a mainstay of Republican Southern politics for years to come.

“Some Republicans gave up on winning the African-American vote, looking the other way or trying to benefit politically from racial polarization,” Mehlman said at the NAACP’s annual convention. “I am here today as the Republican chairman to tell you we were wrong.”

Prior to the 1960s, the South was solidly Democratic, due to the Democrats’ defense of slavery in the Civil War. However, cracks in the facade began to appear amid the Democrats’ support of civil rights starting in 1948 — which led to the split with the Dixiecrats, a short-lived segregationist party composed of conservative Democrats. These cracks became more severe during the civil rights movement, the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and federal intervention toward forcing desegregation.

The “Southern Strategy” was best described by Nixon political strategist Kevin Phillips in a 1970 article from The New York Times: “From now on, the Republicans are never going to get more than 10 to 20 percent of the Negro vote and they don’t need any more than that … but Republicans would be shortsighted if they weakened enforcement of the Voting Rights Act. The more Negroes who register as Democrats in the South, the sooner the Negrophobe whites will quit the Democrats and become Republicans. That’s where the votes are. Without that prodding from the blacks, the whites will backslide into their old comfortable arrangement with the local Democrats.”

The idea was relatively simple: by standing back and allowing black voters to actively fight for their political enfranchisement, this would stroke “white fear” — or the sense that whites are being disenfranchised — in the South to such a degree that these white voters would abandon the Democratic Party for the Republican Party. Until the mid-20th century, black Americans were explicitly denied the right to vote or run for office via the use of disenfranchisement tactics, including poll taxes, literacy tests and “white primaries.” The Republican Party came to see federal intervention against states determining how to run their own elections as a violation of states’ rights — a notion that appealed to Southern conservative Democrats.

In and of itself, the “Southern Strategy” was hypocritical: Nixon was instrumental in passing the Civil Rights Act of 1957 and supported the Civil Rights Acts of 1960, 1964 and 1968, as well as the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The former president’s work in this regard won him the praise of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. However, this move to become the advocate for “states’ rights” proved so attractive that a party which never really believed in it initially jumped on it in as a chance to raise their popular appeal. Nixon won the presidency with 60 percent of the popular vote, largely due to this “strategy.”

This connection between Republicans and “states’ rights” became so pronounced that a Republican stating that he believed in “states’ rights” became code to suggest that he supported the “Southern Strategy.” This notion was reinforced in 1980, when then-presidential candidate Ronald Reagan arrived at his first Southern campaign stop at Neshoba County, Mississippi, and expressed his belief in states’ rights.

Neshoba County is the site of the 1964 Freedom Summer murders, in which James Earl Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner — volunteers participating in the 1964 Freedom Summer voting registration drive — were killed by members of the Ku Klux Klan.

This sense of “white fear” as a defining factor in voting, however, has many doubting the strategy’s ability to function as a long-term solution for Republican viability.

“Many are starting to become skeptical of the Republicans’ insistence for harsher immigration legislation, despite the party’s traditional opposition to government red tape,” said Edward Hudgins, director of advocacy for libertarian think tank The Atlas Society and author of “The Republican Party’s Civil War: Will Freedom Win?,” to MintPress.

“Many are starting to read this as ethnic bias,” Hudgins continued, advising that the GOP should be moving toward inclusion.

“The idea is that the demographics will never again favor the white-only coalition the Republicans have traditionally relied on. To survive, the Republicans must address the needs of not just white evangelical voters, but also black and Hispanic voters, and they must do it in a way that goes beyond just offering lip service. Right now, this is not a big focus of the GOP and this may lead to trouble for the Republicans in the future,” he explained.

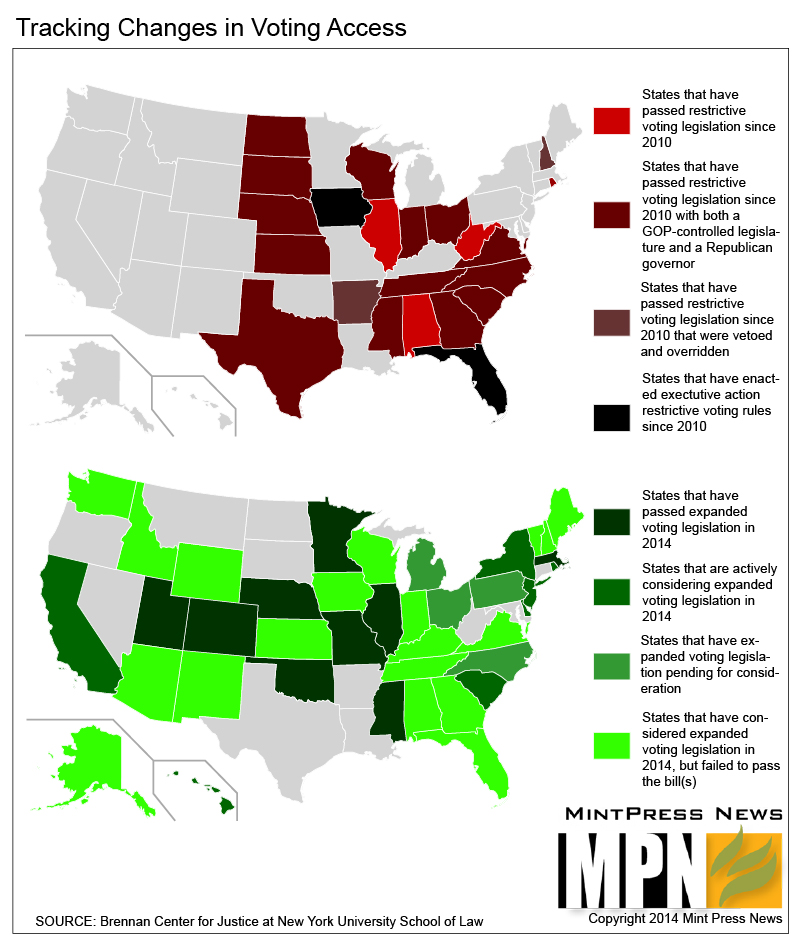

However, the solution most in the GOP have chosen to embrace is to limit the number of Democratic-coalition voters who can vote. Since 2010, 22 states have passed restrictive voting legislation (see Figure 2). These measures limited access to polls, created new identification requirements for voting or denied visiting students the ability to vote in local elections.

The most aggressive example of these new restrictions can be found in North Carolina, a traditionally bluish-purple state which elected, for the first time in recent history, a Republican-controlled government during the 2010 Tea Party sweep. The state has eliminated same-day registration, reduced early voting, ended pre-registration for 16- and 17-year olds and imposed a photo ID requirement. Other rules, such as denying college students the right to vote while at school if their parents still claim them as dependents, were defeated in court.

Looking forward

Stephen Farnsworth is a professor of political science and international affairs and director of the Center for Leadership and Media Studies and the University of Mary Washington in Virginia. In conversation with MintPress, Farnsworth pointed out that while the South is likely to turn purple or even blue in the next 10 to 20 years, U.S. politics are cyclical.

“The primary consideration moving forward in American politics is the increasing diversity of the voting populace,” said Farnsworth. “Both parties will have to deal with an electorate that — 20 years from today — will look quite different from today’s electorate, in the same way the electorate today looks different from what it was 20 years ago.”

As the GOP still sees a higher turnout of white voters in the South, he said, “So Republican control of the South may not disappear any time soon. However, when it does, the Republicans will figure out a new formula for its viability; it will move on.”

Farnsworth said he sees the South as being in the process of changing, and its politics and demographics are beginning to resemble that of the rest of the country. In the future, he believes the South will eradicate its political “uniqueness.”

“Maybe, this is where the South is going in the end — it will rejoin the rest of the Union.”

Figure 2: Charting Changes to the Nation’s Voting Laws.