Source

Published in partnership with Shadowproof.

In the infancy of the Trump presidency, a new community defense network is espousing anti-racist and anti-capitalist politics to build coalitions in cities, small towns, and rural areas across America.

Redneck Revolt recruits predominantly poor and working class white people away from reactionary politics. The organization advances an analysis of their class condition and white supremacy’s role in upholding the wealth and privilege of a small, white elite.

Redneck Revolt inserts themselves into overwhelmingly white spaces—NASCAR races, gun shows, flea markets in rural communities, and country music concerts—to offer a meaningful alternative to the white supremacist groups who often also recruit in those spaces.

The organization’s growing membership comes as media pundits, the Democratic Party, and the United States’ relatively small socialist parties all grapple with how to address the plight of working class white Americans in the wake of Donald Trump’s election.

“Economic anxiety,” a term presented by the media to defend Trump’s ascension, has become an internet meme for acts of racial terror. Hillbilly Elegy author JD Vance has been paraded around to defend and mythologize the travails of working class white Republican voters.

Establishment liberals debate whether these people, particularly in red states, are worth reaching out to at all. They find the ease with which they embrace nativism, social conservatism, and racism might threaten a liberal voting coalition that includes people of color, immigrants, and the LGBTQ community.

Yet the American historical context that animates the Republican Party-working class white alliance is often absent. The historical failure of neoliberalism to present sustainable pathways out of poverty or a meaningful safety net for American workers is scarcely contemplated.

It is unfair to let poor white people off the hook for their lack of solidarity with the rest of the working class. But it is only through engagement, recognition of the failures of both political parties, and organizing for a more radically unified working class politic that these issues can be overcome.

Historically small socialist organizations like Democratic Socialists of America have gained some traction promoting socialist, or more progressive liberal, politics in the wake of Senator Bernie Sanders’ 2016 presidential bid, but Redneck Revolt is not prescriptive in regards to how to confront the inequities of the capitalist state.

“We don’t have some grand plan for how we want to remake the world. We’re tackling a specific problem, which is white supremacy, which we find to be built into capitalism,” said Pittsburgh Redneck Revolt organizer Shaun who, along with Mitch, spoke with Shadowproof about their organizing with Redneck Revolt.

Shaun and Mitch of spoke to Shadowproof about their work with Redneck Revolt. Their last names are being withheld because other members of Redneck Revolt have faced doxxing and harassment by militia members and white supremacists. They don’t want to put their families at greater risk.

“Our gripe with capitalism is it has utterly failed to make the vast majority of people free, because it was never really designed to,” Shaun continued.

“It concentrates wealth in the hands of a small portion of the population, it concentrates power and access to resources in the hands of a small portion of the population, and it leaves the rest of us in a state of variable abjection. It doesn’t work for anybody except the people who are exploiting the rest of us.”

Despite their lack of a prescriptive political ideology, they do have a fairly broad set of principles posted on their website. They include a rejection of capitalism, and “wars of the rich,” standing against “the nation-state and its forces which protect the bosses and the rich” and standing in “organized defense of our communities.” They declare their belief in the “need for revolution.”

Redneck Revolt’s anti-racist, anti-capitalist message seems to be taking hold in communities across the United States. The organization had just 13 chapters in January but has nearly tripled its chapters nationally in the last 6 months. The group now has 34 different branches, 26 of which are in states that voted for Trump. Multiple chapters have over fifty members.

Shaun notes the Pittsburgh chapter is representative of a wide variety of political ideologies, including “anarchists, libertarians, socialists, and even a couple of hold-out Republicans.”

Despite their diverse ideologies and backgrounds, Shaun explains that members are united by their rejection of white supremacy are drawn toward the group’s emphasis on community defense and survival programs.

Anti-Fascism

Redneck Revolt’s community defense strategy extends to showing up to white power rallies, where hate groups broadcast their ideology into the public sphere.

On April 29, members of Redneck Revolt traveled to Pikeville, Kentucky to counter the Traditionalist Worker’s Party (TWP) and the National Socialist Movement.

Nestled within Appalachia, Pikeville has a population of less than 7,000 and a median household income of $22,026. Ninety-five percent of people living there are white and 80 percent voted for Donald Trump.

“I’ve been to events countering the TWP before. They’re a particularly virulent new pan-white power organization,” Shaun said, reflecting on his trip to Pikeville. “They’re doing a lot of work trying to consolidate different white power movements under one umbrella, which is obviously very dangerous.”

“They’ve been very specifically, targeting Appalachia in a lot of their propaganda and organizing in the last couple of years, and as a native Appalachian, I take that very personally.”

“It was really high stress,” Shaun said because the TWP and their allies were specific about “wanting to come armed and use Kentucky’s stand your ground laws as a threat and a bludgeon,” against those who would oppose them. “They definitely showed up in force and armed to the teeth,” he said.

George Ciccariello-Maher is an Associate Professor of Politics and Global Studies at Drexel University, where his work often focuses on left-wing political movements. He said the “result of debating and discussing with fascists and white supremacists is that you’re legitimizing their ideas. And you’re also misunderstanding how it is that those ideas function.”

“The rational idea would be to come together as poor people to fight against the system and yet that systematically doesn’t happen,” Ciccariello-Maher said. “So when you realize white supremacy functions on an irrational level, that it is a system, a structured system of institutionalized irrationality, then you begin to realize that you can’t argue your way out of it. Then you start to realize that the only thing you can do is to fight.”

“We didn’t argue your way into white supremacy and slavery, we’re not going to argue our way out of white supremacy,” Ciccariello-Maher said.

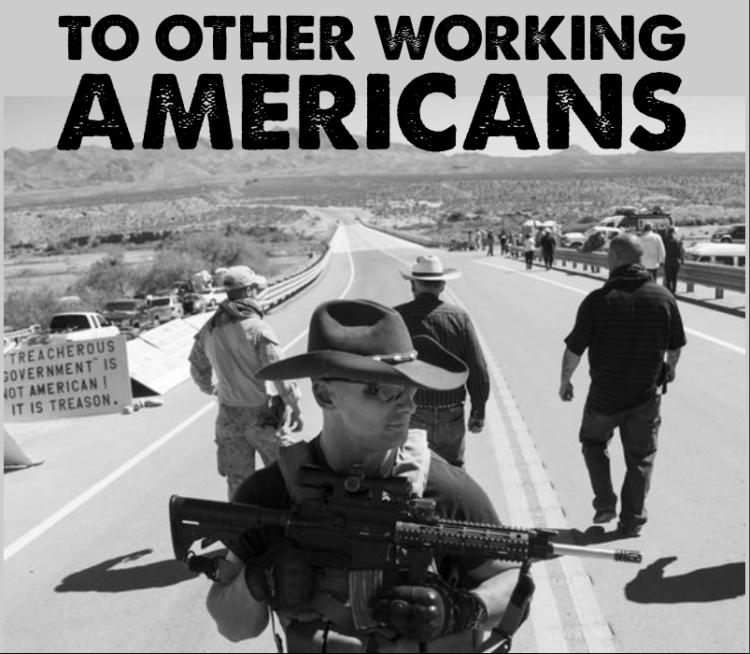

With that in mind, Redneck Revolt emphasizes the importance of teaching armed self-defense to its members and more marginalized communities.

“People need to be able to defend themselves. [We] live in a country in the world where people of color and LGBTQ people are routinely victimized and systematically victimized by the people who claim to be there for their defense,” Shaun said.

“We provide free basic firearms training to pretty much everyone who needs it. We focus on trying to provide [self-defense training] when asked for [by] communities of color and LGBTQ folks.” Their John Brown Solidarity Fund helps community defense initiatives “get off the ground and get training.”

https://twitter.com/PghRevolt/status/863164093045329920

Despite facing heavily armed white supremacists, anti-fascists descended from the region to protest TWP and the National Socialist Movement. The people of Pikeville stood alongside them in opposition to the hate.

These confrontations have not turned violent. There weren’t brawls or property damage like has been seen in Berkeley and Portland. Violence did not break out at Pikeville, or at the proposed KKK rally in Asheboro, NC a week later, or at a MAGA rally in Phoenix, Arizona in March.

Some have speculated that Pikeville remained relatively peaceful because both sides were armed in a state with stand your ground laws, where a fight would inevitably lead to the discharging of firearms, a chilling deterrent.

The KKK never even bothered to show up in Asheboro, but the local Silver Valley Redneck Revolt managed to put together a counter-rally of approximately 100 people. Another community group organized similar numbers to march as well.

Shaun applauded the Pikeville community’s resistance. “There was a complete refusal to let that fear stop them from showing up to do everything they could to keep it from being some sort of a walk of victory,” Shaun said. “And that was intensely inspiring because people were scared and people were afraid and they showed up anyway. And they showed up organized and in force.”

Regardless of their political affiliation, Pikeville residents “came out and took a stand, a very vocal stand against white power movements trying to move into their territory and consolidate power. In fact, some of the locals were some of the loudest, most strident anti-fascist voices there.”

Survival Pending Revolution

“There’s a narrative that a lot of the media misses about rural areas,” said Mitch, a member of Redneck Revolt’s Silver Valley chapter.

“The perception is that Appalachia and the deep south is just inundated with racist white supremacists. It’s no secret that there’s certainly a higher concentration in those areas,” Mitch said, “but there’s also swaths of disaffected people who want nothing to do with politics, who don’t think that they can be represented by politicians, and are tired of being jerked around by both parties.”

“They don’t like liberals and they don’t like conservatives. They want to take care of their needs and they’re kind of at the behest of all these other parties that are just jerking them around and they’re just tired of it. That’s part of the demographic that we have a lot of messaging to.”

Mitch described the lack of infrastructure, services, and meaningful political representation in his community in rural North Carolina as the setting where reactionary politics can easily take hold and where presidential elections generally represent a choice between two politicians with nothing meaningful to offer.

“Scattered throughout Silver Valley are some pretty low-income places and very much rural ghettos in the form of trailer parks and just really low-income housing that nobody bats an eye at, or tries to meet their needs, or organize with them. They’re really forgotten communities,” he said.

Redneck Revolt provides survival assistance tailored to the needs of their local community. This includes food programs, community gardens, clothing programs, and needle exchanges in addition to their armed self-defense programs.

Mitch has a garden on his property, on about ⅓ acre of land, where members try to connect with nearby low-income and rural communities to provide free fresh food.

“We get people invested — time and energy wise — into working with us and finding ways to empower those communities to grow their own food, so that it doesn’t have to come just through charity. It’s not just us giving away food, it’s the community itself finding ways to come together to feed their own,” Mitch said.

In the future, Silver Valley members want to assist with distributing Meloxin and other medical supplies and provide free clinics. “You’ve got to root yourself in the community first and see what their needs are and move to organize in that manner from there,” he said.

Considering Redneck Revolt’s vision, their embrace of the term ‘redneck,’ their belief in building solidarity with working and poor communities, their recruitment within rural white communities, and their embrace of late ‘60’s-style survival programs, it is hard not to draw parallels to the original Rainbow Coalition, and specifically to the Young Patriots (YPO).

The Rainbow Coalition was an attempt—initially lead by Fred Hampton and the Chicago chapter of the Black Panther Party in the late 1960s—to unify the Black Power movement led by the Black Panther Party, the Puerto Rican Nationalist movement led by the Young Lords, and a white working class movement led by the YPO in Chicago.

Shaun confirms that members recognize parallels with the YPO internally.

“The YPO is a huge inspiration for us, specifically because it’s one of the most visible instances of that sort of rupturing racial lines when folks from different demographics were able to step back and realize that their interests allied with one another, not with a politician or a company,” he said.

“There was a real tangible understanding that their liberation was bound up with one another’s liberation. So we draw a lot of really explicit inspiration from the YPO and the work that they did with the Chicago Panthers and the Young Lords.”

Professor Ciccariello-Maher believes that while the Young Lords should be an aspiration, organizers must be prepared for the challenges of coalitions.

“The danger of a Rainbow Coalition is that you can run into a left wing politics that, for example, asks Black Americans to stand-down with their complaints to embrace a broader coalition,” he said.

Ciccariello-Maher cited the Communist Party USA’s organizing as an example.

“I like to think of this in terms of an opposition that comes out of the old Communist Party strategy of what was called ‘unite and fight.’ The U.S. Communist party, over a certain period, had a really incredible history of contributing to struggles against white supremacy in the U.S.”

“It was really the main organization accomplishing these aims, but also had its limitations—in particular, when it retreated from those struggles, it argued essentially that workers should unite and fight, meaning a kind of lowest common denominator of what Black and white workers could agree on. The result of this was really to erase the centrality of white supremacy in the workplace and in US history.”

In a modern context, Ciccariello-Maher suggests it’s “Not just how can we get together, you know can Black, white, and brown agree to fight for 15 — the question is what helps us to overcome the very real divisions of the poor and working classes and sometimes that means fighting against white workers, over racial privileges.”

“We need to see these things in motion, we need to understand the ways in which we could build a Rainbow Coalition, but one that understands the historic weight of anti-Blackness or one that understands the historical weight of Indigenous Genocide or of U.S. Imperialism in Latin America.”

Ciccariello-Maher believes W.E.B.s Du Bois’ Black Reconstruction In America provides valuable historical lessons, supporting Redneck Revolt’s principles of standing against white supremacy, capitalism, and the wars of the rich. For Du Bois, the story of the white working class is a tragedy.

“It’s the betrayal of a shared class condition,” Cicariello-Maher said. “Du Bois is so struck by the fact that poor whites and slaves had so much in common and had so much potential for solidarity, and yet ultimately poor whites sided with the slaveowners and sided with what Du Bois called ‘the petty wages of whiteness.’ Psychological wages that make you feel better than someone else, but also material wages in the sense that you can work as a slave catcher and that’s better than not having any job at all.”

Shaun from Pittsburgh’s chapter of Redneck Revolt discussed the conditions of these “psychological wages.”

Shaun likes to tell potential members, “white supremacy is essentially a fight to be the best-treated dog in the kennel.”

“All poor and working class folks suffer at the hands of the rich. We all have trouble — bordering to the point of impossibility — making house rent, paying medical bills especially these days, covering food, making sure that our children and families are cared for and it doesn’t have to be that way,” he said.

“It’s that way because a vastly small percentage of the population hordes access to resources and they’re able to do this because they’ve managed to get one-half of the working class to turn against the other half in exchange for basically preferential treatment.”

“It’s in everyone’s best interests that we as quickly and aggressively as possible dismantle that system so that poor and working folks essentially have something resembling a fair shake at a decent life.”