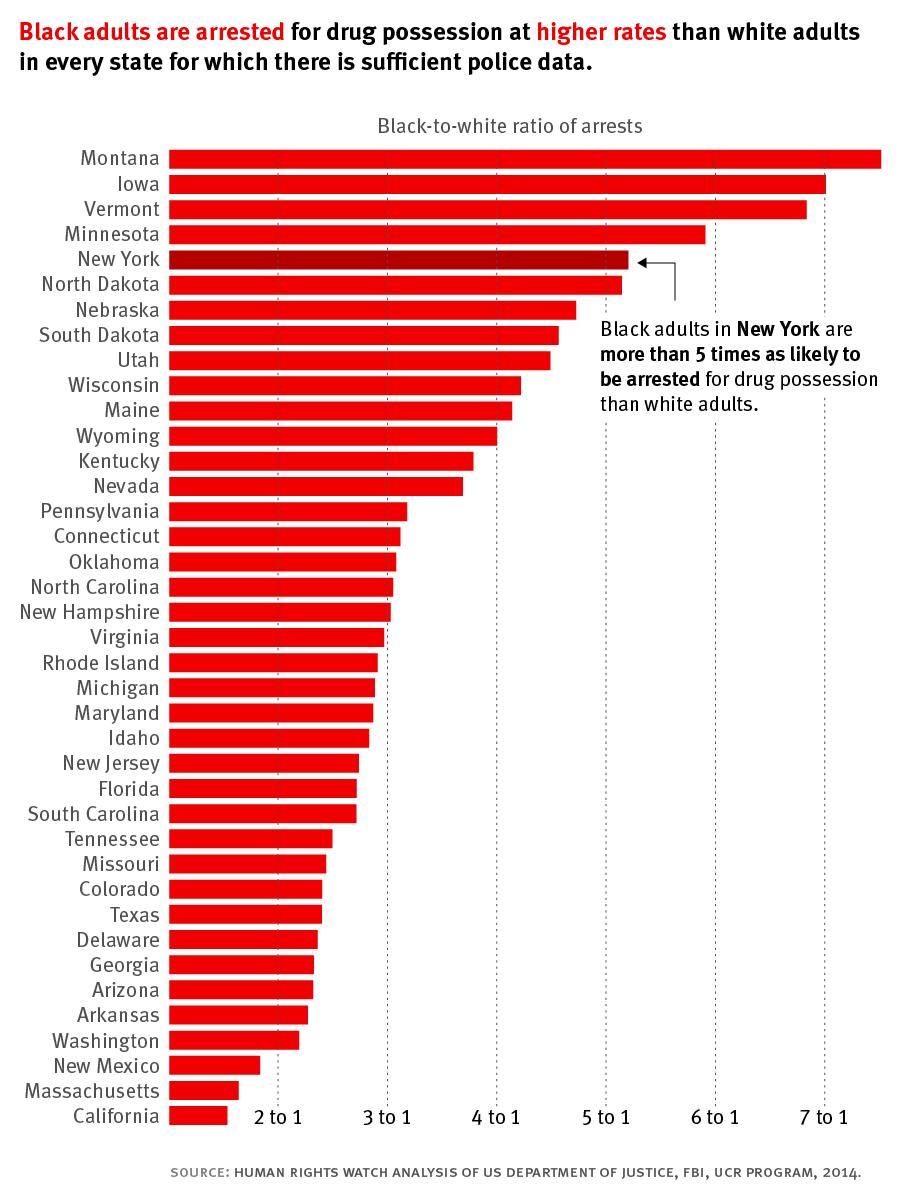

The massive enforcement of laws criminalizing personal drug use and possession in the United States causes devastating harm, Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) said in a joint report released today. Enforcement ruins individual and family lives, discriminates against people of color, and undermines public health. The federal and state governments should decriminalize the personal use and possession of illicit drugs.

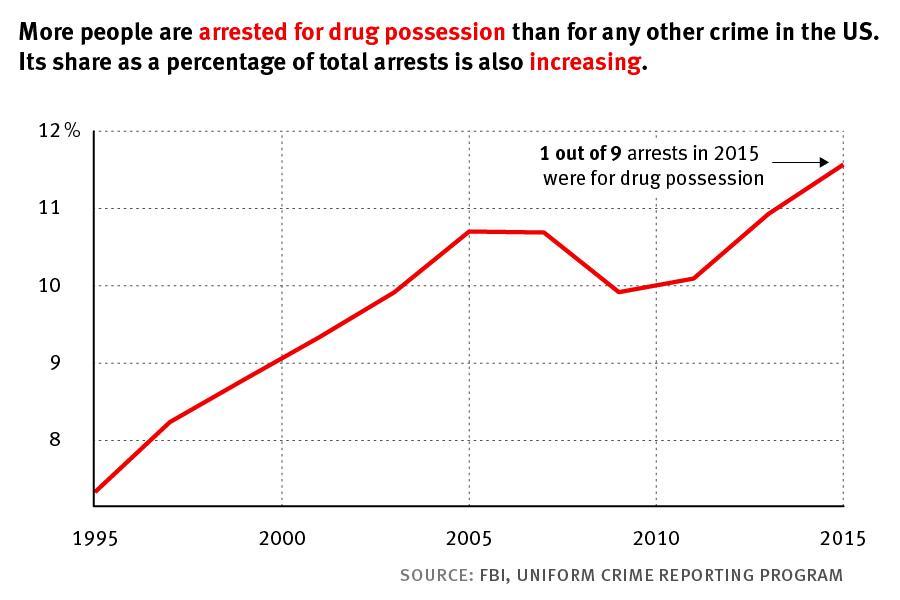

The 196-page report, “Every 25 Seconds: The Human Toll of Criminalizing Drug Use in the United States,” finds that enforcement of drug possession laws causes extensive and unjustifiable harm to individuals and communities across the country. The long-term consequences can separate families; exclude people from job opportunities, welfare assistance, public housing, and voting; and expose them to discrimination and stigma for a lifetime. While more people are arrested for simple drug possession in the US than for any other crime, mainstream discussions of criminal justice reform rarely question whether drug use should be criminalized at all.

“Every 25 seconds someone is funneled into the criminal justice system, accused of nothing more than possessing drugs for personal use,” said Tess Borden, Aryeh Neier Fellow at Human Rights Watch and the ACLU and the report’s author. “These wide-scale arrests have destroyed countless lives while doing nothing to help people who struggle with dependence.”

The organizations interviewed 149 people prosecuted for using drugs in Louisiana, Texas, Florida, and New York – 64 of whom were in custody – and 217 other individuals, including family members of those prosecuted, current and former government officials, defense attorneys, service providers, and activists. The organizations also did extensive new analysis of data obtained from Texas, Florida, New York, and the FBI.

The massive enforcement of laws criminalizing personal drug use and possession in the United States causes devastating harm.

Among those interviewed was “Neal,” whose name, like that of some others, was changed to protect his privacy. “Neal” has a rare autoimmune disease and is serving five years in a Louisiana prison for possessing less than 0.2 grams of crack cocaine. He said he cried the day he pled guilty because he knew he might not survive his sentence.

Another is Corey, serving 17 years in Louisiana for possessing half an ounce of marijuana. His 4-year-old daughter Charlee, who has never seen him outside prison, thinks she visits him at work. A third is “Nicole,” who after being held pretrial for months in a Houston jail, separated from her three young children, finally pled guilty to her first felony. The conviction, for possessing heroin residue in an empty baggie, meant she would lose her student financial aid, job opportunities, and the food stamps she had relied on to feed her children.

“Do they realize what they are doing to people’s lives in here?” said “Matthew,” from the Hood County jail in Texas. “Because of my drug addiction, they just keep punishing me… They never offered me no help. I have been to prison five times, and it’s destroyed me.”

“Matthew” was sentenced to 15 years for possession of an amount of methamphetamines so small the laboratory could not even weigh it. The lab result simply read “trace.” His prior convictions were mostly out-of-state and related to his drug dependence.

“While families, friends, and neighbors understandably want government to take action to prevent the potential harm caused by drug use, criminalization is not the answer,” Borden said. “Locking people up for using drugs causes tremendous harm, while doing nothing to help those who need and want treatment.”

Four decades after US President Richard Nixon declared a “war on drugs,” rates of use have not significantly declined. People who need treatment often find it is unavailable, and criminalization tends to drive people who use drugs underground, making it less likely that they will get care and more likely that they will engage in unsafe practices that make them vulnerable to disease and overdoses.

“When you’re a low-income person of color using drugs, you’re criminalized – that means demonized, marginalized, stigmatized…. When we’re locked up, we’re not only locked in but also locked out. Locked out of housing…. Locked out of employment and other services. Locked into a class that’s underclass – you’re a fixed class; you’re not a person anymore, because you had a drug.”

–Cameron Barnes, New York City, arrested repeatedly for drug possession by New York City police from the 1980s until 2012.

“You get thrown in here. You don’t have any contact with the outside world. I’m waiting on everybody else. Everything is crumbling.”

–Breanna Wheeler, speaking from jail in Galveston, Texas, where she was detained pretrial for methamphetamine residue in a baggie. A single mother, she eventually pled to her first felony conviction and time served so she could return home to her 9-year-old daughter.

“I’ve been in here for four months, and [my job] was the only income for my family…. [Their] water has been cut off since I’ve been in here. The lights were cut off…. Basically that’s what happens when people come here. It doesn’t just affect us, but it affects everyone around us.”

–Allen Searle, speaking from jail in St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana, where he had been detained pretrial for almost 100 days.

“You’re starting life over. You can’t expect to be absent from society and just walk back in. You’ve lost everything – your job, apartment, whatever you had before you’re going to lose that…. Because I caught this felony, I was on the street for five years. I had never been homeless before…. [Y]ou walk out of those [prison] gates and you’re on your own.”

–Charlie West, a former US military medic, describing his re-entry after incarceration for felony possession of cocaine in New York City in 2010.

“I don’t see why [the felony record is] defining. It’s not like we’re a minority; they’re making us a majority. If a matter comes up that is important to me, I can’t vote and make a difference in the world…. You don’t realize – the vote – how important that stuff is until you lose it. I was convicted at 18; I had never been able to vote yet…. I found my voter registration card. I thought, here’s a good high school memory of when me and my friend got registration cards. Now I can’t use it. I just threw it out.”

–Trisha Richardson in Auburndale, Florida, one of three states to impose lifetime disenfranchisement, convicted of possession of Xanax and methamphetamines.

“The felony conviction is going to ruin my life…. I’ll pay for it for[ever]. Because of my record, I don’t know how or where I’ll start rebuilding my life: school, job, government benefits are now all off the table for me. Besides the punishment even [of prison]…. It’s my whole future.”

–Nicole Bishop, speaking from the Harris County Jail, where she was detained pretrial for heroin residue in a baggie and cocaine residue inside a plastic straw.

“Food stamps, you can’t get them for a year. So you go dig in a dumpster. My food stamps are for my kids, not me.”

–Melissa Wright, on probation in drug court after pleading guilty in Covington, Louisiana.

“Trace cases need to be reevaluated. If you’re being charged with a .01 for a controlled substance, … that’s an empty baggie, that’s an empty pipe. There used to be something in it. They are ruining people’s lives over it.”

–Alyssa Burns, speaking from the Harris County Jail, where she was detained pretrial for methamphetamine residue inside a pipe.

“I remember when they said I was guilty in the courtroom, the wind was knocked out of me. I went, ‘the rest of my life?’ … All I could think about is that I could never do anything enjoyable in my life again. Never like be in love with someone and be alone with them… never be able to use a cell phone…take a shower in private, use the bathroom in private.… There’s 60 people in my cell, and only one of us has gone to trial. They are afraid to be in my situation.”

–Jennifer Edwards, speaking from jail in St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana, about the jury’s guilty verdict. Because of her prior drug possession convictions, she faced a minimum of 20 years to life in prison for possessing a small amount of heroin.