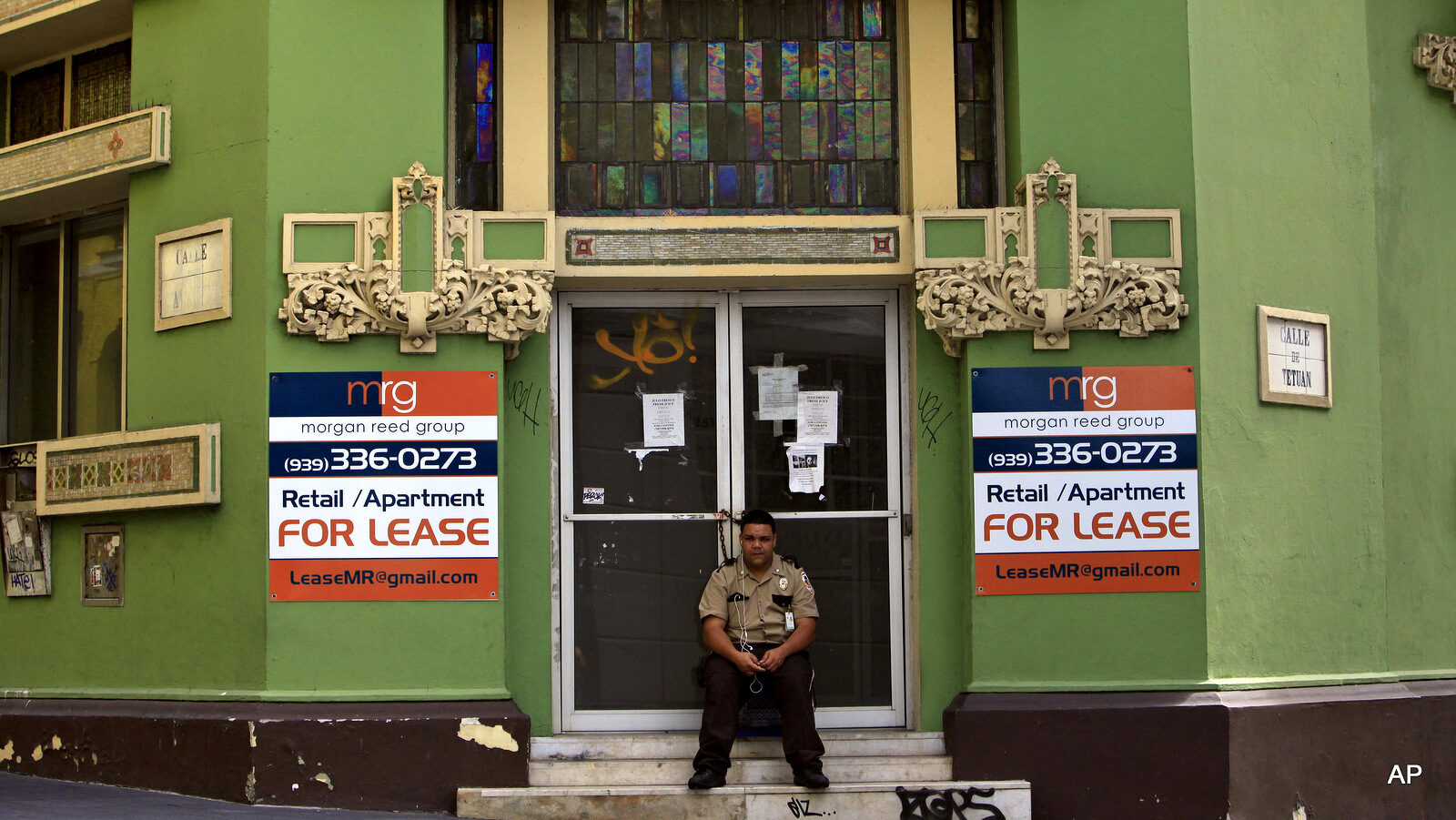

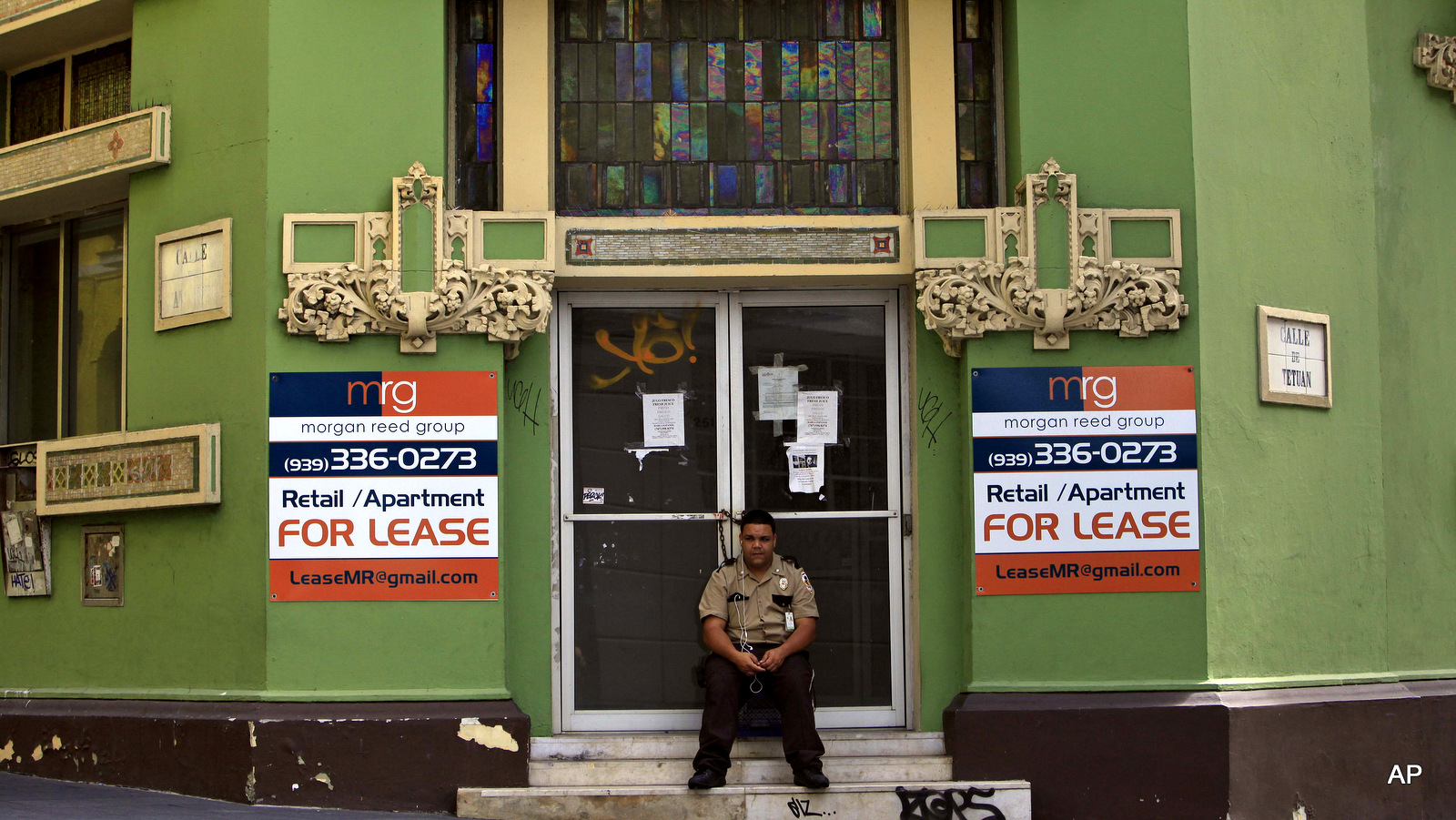

WASHINGTON — Hundreds of thousands of residents of Puerto Rico are being forced from their homeland in search of better economic conditions on mainland America. The Caribbean island recently defaulted on a $58 million debt for the first time in its history, and the super rich are descending upon the island to buy up homes and businesses that have been abandoned amid hard economic times.

“What you’re seeing then, if this is allowed to continue unchecked, is the gentrification of an entire island,” said Nelson A. Denis, a former New York State assemblyman and author of “War Against All Puerto Ricans: Revolution and Terror in America’s Colony,” while speaking to MintPress News.

Denis was speaking specifically about tax exemptions enacted on the island in 2012 to encourage wealthy individuals, mainly from the mainland United States, to move to the island and start new businesses there.

It’s just one of the solutions the country drummed up to rehabilitate its ailing economy.

As the wealthy come to the island, tens of thousands of Puerto Ricans are pouring out. From 2000 to 2013, the Caribbean island’s population declined by 200,000 people — a trend that the Census Bureau expects to continue until at least until 2050, according to the Pew Research Center.

The Washington-based nonpartisan think tank reported last year: “Puerto Ricans have left the financially troubled island for the U.S. mainland this decade in their largest numbers since the Great Migration after World War II, citing job-related reasons above all others.”

Gentrifying a country

Aiming to attract big investors via tax incentives isn’t unique to Puerto Rico. Indeed, many cities and municipalities across the U.S. have adopted the same strategy in a bid to grapple with their own financial woes.

In 2012, the unincorporated U.S. territory enacted the Export Services Act (Act 20) and the Individual Investors Act (Act 22), which provide tax exemptions to encourage wealthy individuals to move to the island. The incentives include a 0-percent tax on earnings and profits, a 3- to 4-percent flat income tax, and a 0-percent property tax. There’s also a 0-percent tax on dividends and interest, and a 0- to 10-percent tax on long-term capital gains, which can be as high as 20 percent in the U.S.

The incentives are working. The rich have arrived. But the problem is that everybody else is leaving.

“The highest beneficiary of that right now is a fella named John Paulson, a hedge fund owner,” Nelson Denis, the former assemblyman, told MintPress.

Paulson is the infamous owner of the hedge fund Paulson & Co. He captured the public’s fascination during the 2007 and 2008 financial crisis, when he made $15 billion in profits by betting against American homeowners, who suffered heavy losses when the subprime mortgage market crashed. Occupy Wall Street protesters gathered in front of his home to show their disdain in 2011, and left him a novelty $5 billion tax refund check.

“This dude, John Paulson, is now under the aegis of Act 22 in Puerto Rico, using that law, and he’s developing a $500 million hotel and condominium resort on Dorado Beach,” said Denis.

According to Forbes, Paulson will have invested $1.5 billion in ultra-luxury real estates in Puerto Rico by the end of this year. These properties include the St. Regis Bahia Beach Resort and the Condado Vanderbilt Hotel.

“So John Paulson, who profited from betting against homeowners and buying up distressed properties in 2007, is, eight years later, doing the same thing in Puerto Rico with almost the identical scenario!” quipped Denis.

“He gets tax preferences that other people don’t. He benefits from people that have to leave the island, leaving their homes and businesses and whatever else behind, and buys up distressed properties for pennies on the dollar.”

‘This is not politics, this is math’

Earlier this month, Puerto Rico defaulted on a $58 million payment it was supposed to make to the Public Financing Corporation, a subsidiary of the Puerto Rico Government Development Bank. It paid only $628,000 of that debt. It was the first time this has happened in the island’s history.

The island’s governor, Alejandro García Padilla, told The New York Times in June, “The debt is not payable. There is no other option. I would love to have an easier option. This is not politics, this is math.”

“My administration is doing everything not to default… But we have to make the economy grow,” he added. “If not, we will be in a death spiral.”

Roughly $11.3 billion of Puerto Rico’s $73 billion in total debt is owned by bond mutual funds, while $15 billion of it is owned by hedge funds, according to CNNMoney. The rest, approximately $26.5 billion, is owned mainly by Puerto Ricans and mainland Americans, reported the financial news outlet.

This spells trouble not only for Puerto Rico but the world financial market, as well as ordinary people on both the island and the mainland. The destructive nature of toxic debt was made apparent in 2007, when the American subprime loan market crashed the global economy.

According to CNNMoney, more than 20 percent of bond mutual funds own Puerto Rican bonds. “[T]he exact numbers are 377 funds out of 1,884 United States bond mutual funds,” the financial news agency reported in July, citing figures from Morningstar.

Ordinary Puerto Ricans are in danger as well because they own most of this debt.

“I am worried. Any Puerto Rican is worried,” said Rey J. de Leon, a Puerto Rican lawyer, to CNNMoney.

“We have a lot of people who are seniors and they depend on the returns from those bonds to live on a month-to-month basis,” he explained.

The path to gentrification: Self-Inflicted and historical

The island’s financial woes stem from structural aspects related to the legacy of colonization by the United States, as well as a self-inflicted dimension related to government administrations and the types of policies they’ve enacted, according to Ian J. Seda-Irizarry, assistant professor of Economics at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York and political advisor to the Working People’s Party of Puerto Rico.

“The government of Puerto Rico wants to continue with this model that has been obsolete since the 1970s,” Seda-Irizarry told MintPress, referring to the fact that both current and past administrations have resorted to treating the economy with neoliberal reforms, which only make the situation worse.

Writing this month in Jacobin, a magazine that describes itself as the “leading voice of the American left,” Seda-Irizarry and Heriberto Martínez-Otero described the dire straits of the Puerto Rican economy.

“Per capita income in Puerto Rico is almost half that of Mississippi, the US’s poorest state. The jobless rate is 12.6%; in West Virginia, the state with the highest unemployment rate in the US, that number is 7.4%. Puerto Rico’s labor participation rate is around 43%, 20 points lower than in the US as a whole. Median household income is almost $7,000 less than in Detroit (and less than half of the US average). And a staggering 45% of the population lives in poverty (compared to about 15% in the US).”

The island government has attempted to address the crisis by trying to make it a more attractive investment destination and implementing austerity measures. This is the economic model that Seda-Irizarry says is obsolete.

Indeed, numerous studies have shown that the time to implement austerity is during an economic boom, not a crisis. Yet austerity is the direction Seda-Irizarry says the Puerto Rican government is about to take. “So in that sense,” he said, “if we don’t get rid of this political class we’re not going to move forward.”

In the past, it was pharmaceutical companies, like Pfizer, along with chemical and electronics corporations, such as Hewlett Packard, that flocked to Puerto Rico’s tax haven, but they did not invest in the country. When other countries around the world became even cheaper than Puerto Rico, those companies moved on, leaving little behind.

The colonization of Puerto Rico

The island was annexed by the U.S. in 1898 following the Spanish-American War.

Hurricane San Ciriaco hit the island the following year. It was the longest-lived hurricane in Atlantic Ocean history, lasting almost 30 days. It killed over 3,000 people in Puerto Rico alone, and led to $20 million in damages. In short, it was devastating.

According to Stuart B. Schwartz, Chair of the Council on Latin American & Iberian Studies at Yale University, the U.S. provided as much aid as it fit in with its political machinations for the island, which included its state as a colonial project.

Nelson Denis agrees with this sentiment, telling MintPress that the U.S. didn’t send Puerto Rico the relief the island wanted in order to manipulate the crisis so it could push through policies of its own choosing without resistance on the island.

“It kind of worked perfectly into the Naomi Klein ‘Shock Doctrine.’ You [the U.S.] benefit from this tragedy, from economic distress,” he said.

One year later, the U.S. took greater control over the island’s economic policy. It outlawed and devalued the peso. One peso was now worth only 60 American cents.

“It was a strict, straight-up devaluation of 40 percent of their wealth,” said Denis.

Imagine, he said, what would happen if 40 percent of everybody’s wealth and property in the mainland U.S. was eliminated while at the same time 40 percent of their debt went up. This is what happened in Puerto Rico, he explained.

The following year, 1901, the first U.S. civilian governor of Puerto Rico, Charles Herbert Allen, enacted the Hollander Act, which created an unprecedented set of steeply graduated property taxes on every farm in Puerto Rico.

Then, a predatory lender, the American Colonial Bank, stepped in to give out loans to poor Puerto Rican farmers in danger of losing their farms and livelihoods. The bank didn’t have any usury law restrictions so it could charge whatever it wanted, explained Denis.

“They preferred people to go into default because then they could own the farms, and that’s what happened,” he said.

“Within 20 to 30 years, 80 percent of the most arable land in Puerto Rico was owned by North American banking syndicates, and they turned Puerto Rico into a one crop, cash-cow economy, that of sugarcane.”

By 1930, only four sugarcane centrales, the main company conglomerates, owned over half of the sugarcane lands in Puerto Rico. Those companies were Central Guanica, South Puerto Rico, Fajardo Sugar and East Puerto Rico Sugar. Puerto Ricans were now getting jobs on the same sugarcane fields that they had previously owned. Workers attempted to implement a minimum wage, but the U.S. Supreme Court deemed it unconstitutional.

At that point, rank-and-file union workers started to seek help from a man named Pedro Albizu Campos, the main figure in Denis’ book, “War Against All Puerto Ricans: Revolution and Terror in America’s Colony.” Campos was a graduate of Harvard Law School and president of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party. He and his party started to win concessions from the U.S. government, and wages rose from 75 cents a day to $1.50 a day, according to Denis.

“That spelled the difference for a lot of families between starving and living in Puerto Rico, so that was a great thing,” he said.

However, the U.S. began to perceive Campos as a national security threat because he was empowering workers on the island, which didn’t sit well with sugarcane plantation owners, especially in 1935, when the U.S. was in the midst of the Great Depression. Then-President Franklin Delano Roosevelt sent a new governor and chief of police to the island, who militarized the police and started killing nationalists.

Campos himself was targeted by the FBI, attacked, and jailed for 24 years, where he was beaten and tortured. He was released after suffering a stroke in 1964. This movement against nationalists, like Campos, effectively destroyed aspirations for independence. It’s also likely why there isn’t a large movement behind more radical policies for change on the island today.

However, it is the current self-inflicted policies of austerity and an environmental crisis that Ian J. Seda-Irizarry hopes will lead to a “social explosion” that will prompt a people-driven movement for change on the island.

“The purpose of organizations like mine and others is to precisely connect that inefficiency and looting of the resources of all of these administrations and their offices to how the economy has been organized,” he said.

Seda-Irizarry, who is hoping for a more radically left party to be elected into office, concluded: “The ground [in Puerto Rico] is fertile for things, as in many many places all over the world.”