Nothing I am about to write should be read as diminishing in any way my sympathy for Salman Rushdie, or my outrage at the appalling attack on him. Those who more than 30 years ago put a fatwa on his head after he wrote the novel, “The Satanic Verses,” made this assault possible. They deserve contempt. I wish him a speedy recovery.

But my natural compassion for a victim of violence and my regularly expressed support for free speech should not at the same time blind me or you to the cant and hypocrisy generated by his stabbing on Friday, just as he was about to give a talk in a town in Western New York.

British prime minister Boris Johnson said he was “appalled that Sir Salman Rushdie has been stabbed while exercising a right we should never cease to defend.” His Chancellor, Rishi Sunak, one of the last two contenders for Johnson’s crown, concurred, describing the novelist as “a champion of free speech and artistic freedom”.

Across the Atlantic, President Joe Biden stressed Rushdie’s qualities: “Truth. Courage. Resilience. The ability to share ideas without fear… We reaffirm our commitment to those deeply American values in solidarity with Rushdie and all those who stand for freedom of expression.”

The truth is that the vast majority of those claiming this as an attack not only on a prominent writer but on Western society and its freedoms, have been missing in action for the past several years as the biggest threat to those freedoms unfolded. Or, in the case of Western government leaders, they have actively conspired in the undermining of those freedoms.

Prominent figures and organizations now expressing their solidarity with Rushdie have kept their heads down, or spoken in hushed tones against – or, worse still, become cheerleaders for – this much more serious assault: on our right to know what mass crimes have been committed against others in our name.

Rushdie has won trenchant support from Western liberals and conservatives alike, not for being a brave articulator of difficult truths, but because of who his enemies are.

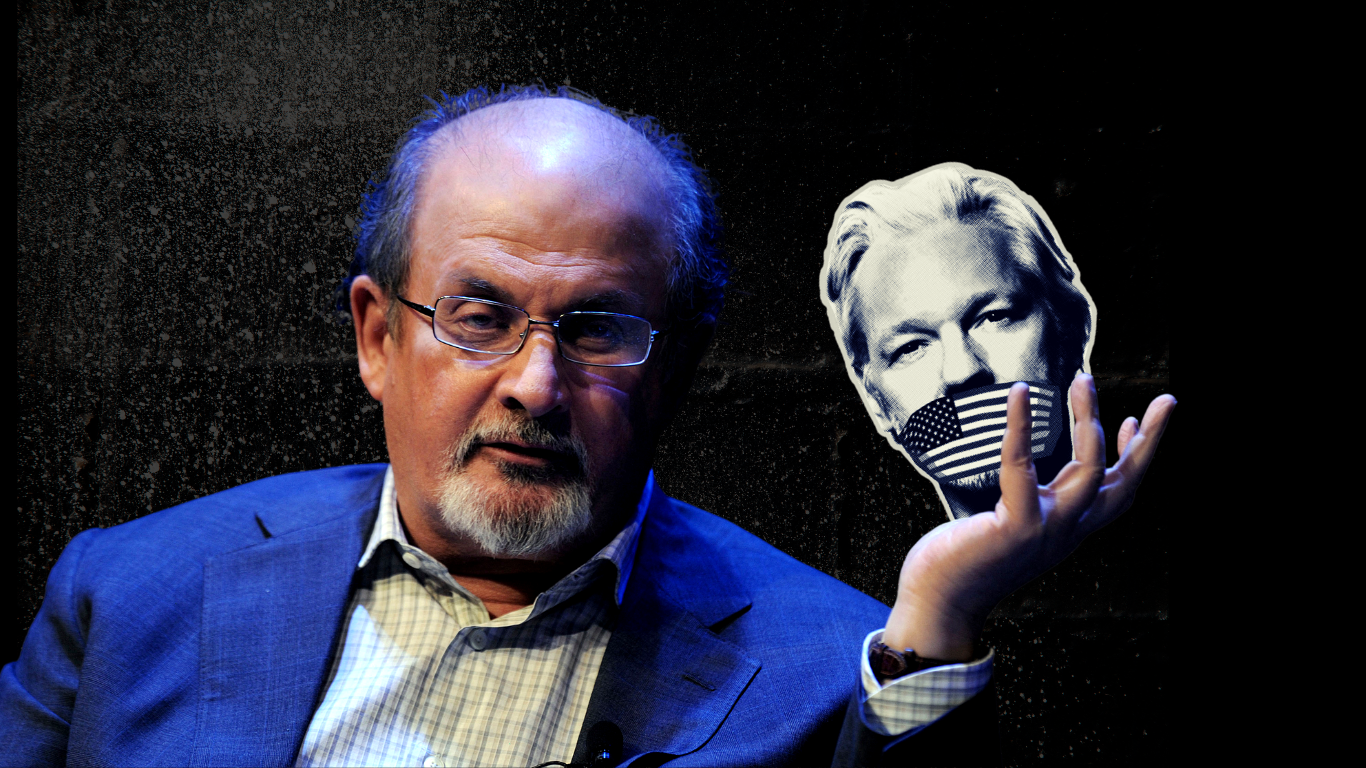

Holding up a mirror

If that sounds uncharitable or nonsensical, consider this. Julian Assange has spent more than three years in solitary confinement in a high-security prison in London (and before that, seven years confined to a small room in Ecuador’s embassy), in conditions Nils Melzer, the former United Nation’s expert on torture, has described as extreme psychological torture.

Melzer and many others fear for Assange’s life if British and U.S. authorities succeed in dragging out much longer the Wikileaks founder’s detention on what amounts to purely political charges. Assange has already suffered a stroke – as Melzer notes, one of the many potential physical reactions suffered by those enduring prolonged confinement.

And all of this is happening to him, remember, for one reason alone: because he published documents proving that, under cover of a bogus humanitarianism, Western governments were committing crimes against peoples in distant lands. Assange faces charges under the draconian Espionage Act only because he made public the gruesome truth about Western military actions in places like Iraq and Afghanistan.

Yes, there are differences between Rushdie and Assange’s respective cases, but those differences should elicit more concern for Assange’s plight than Rushdie’s. In practice, the exact opposite has happened.

Rushdie’s right to free speech has been championed because he exercised it to imagine an alternative formative history of Islam and implicitly question the authority of clerics and governments in far-off lands.

Assange’s right to free speech has been ridiculed, ignored or at best supported weakly and equivocally because he exercised it to hold up a mirror to the West, showing exactly what our governments are doing, in secret, in many of those same far-off lands.

Rushdie’s right to life was threatened by distant clerics and governments for questioning the moral basis of their power. Assange’s right to life is threatened by Western governments because he questioned the moral basis of their power.

Worthy victims

If we lived in functioning democratic societies in the West – ones where power is not so deeply entrenched we are largely blind to its exercise – no journalist, no media commentator, no writer, no politician would fail to understand that Assange’s plight deserves far more attention and expressions of concern than Rushdie’s.

It is our own governments, not “mad mullahs” in Iran, who threaten the free society that permitted Rushdie to publish his novel. If Assange is crushed, so is the basis of our fundamental democratic rights: to know what is being done in our name and to hold our leaders to account.

If Rushdie is silenced, we will still have those freedoms, even if, as individuals, we will feel a little more nervous about saying anything that might be construed as an insult to the Prophet Mohammed.

So why are the vast majority of us so much more invested in Rushdie’s fate than Assange’s? Simply because our sympathy has been elicited for one of them and not the other.

Ultimately, that has nothing to do with whether one or the other is more worthy, more of a victim. It has to do with how much they have, or have not, served the interests of a Western narrative that constantly reinforces the idea that we are the Good Guys and they are the Bad Guys.

Rushdie and the fatwa against him became a cause célèbre for Western elites because he offered a literary sensibility to one of the West’s most cherished modern pieties: that Islam poses an existential threat to the values of an enlightened West. Here was a man, born to a Muslim family in India, attacking the religion he supposedly knew best. He was an insider spilling the beans, stating what other Muslims were supposedly too cowed to admit in public.

Though it was doubtless not his intention or his fault, he was quickly adopted as a literary mascot by Western liberals who were pushing their own “clash of civilizations” thesis. That is not a judgment on the merits of his novel – I am not equipped to make that assessment – but a judgment on the motivations of so many of his champions and on why his work resonates so strongly with them.

Racist worldview

In a real sense, that is true of all literature. It earns its status within a cultural milieu, one policed by media elites with their own agendas. It is they who decide whether a manuscript is published or discarded, whether the subsequent book is reviewed or ignored, whether it is celebrated or ridiculed, whether it is promoted or falls into obscurity.

We tell ourselves, or we are told, that this process of weeding out is decided strictly on the basis of merit. But if we pause to think, the reality is that a work finds an audience only if it stays within a socially constructed consensus that gives it meaning or if it challenges that consensus at a time when the consensus is overdue being challenged.

George Orwell is a good example of how this works. He prospered – or at least his reputation did – from the fact that he questioned certainties about the “natural order” that had long been enforced by Western elites but had become hard to sustain after two world wars in quick succession. At the same time, he exposed the dangers of an authoritarianism that could be easily ascribed to the West’s main adversary, the Soviet Union.

Orwell’s body of work contains ideas that speak to universal values. But that is only part of the reason it has endured. It also benefited from the fact that the ambiguity inherent in those universal lessons could be recruited to a much narrower agenda by Western elites, readying for a Cold War that was about to become the tragic legacy of those two preceding hot wars.

Much the same is true of Rushdie. His novel served two functions: First, its main theme chimed with Western elites because it reassured them that their prejudice against the Muslim world was fully justified – not least because the novel provoked a violent backlash that appeared to confirm those prejudices.

And second, “The Satanic Verses” indemnified Western elites against the accusation of racism. Rushdie inadvertently provided the alibi they so desperately needed to promote their racist worldview of a civilized West opposed by a barbaric, insecure East. It served as midwife to the rantings of Islamophobic tracts like Melanie Phillips’ “Londonistan” and Nick Cohen’s “What’s Left?”.

Literary sedition

For the past two decades, we have been living with the appalling consequences of the West’s smug condescension, its wild posturings, its violent humanitarianism – all masking a thirst for the Middle East’s most precious resource: oil.

The result has been the wrecking of whole countries; the ending of more than a million lives, with millions more made homeless; a backlash that has unleashed even more terrifying forms of Islamist extremism; a deepening self-righteousness among Western elites that has ushered in an all-out assault on democratic controls; an entrenchment of the power of the war industries and their lobbies; and a relentless undermining of international institutions and international law.

And all this has served as an endless excuse to delay addressing the real issue plaguing humanity: the imminent extinction of our species, caused by our addiction to the very resource that got us into this mess in the first place.

Sadly, the attack on Rushdie, and the ensuing indignation, will only intensify the trends noted above. None of that is Rushdie’s fault, of course. His desire to question the authority of the clerical bullies he grew up among is an entirely separate matter from the purposes to which Western elites have harnessed his personal act of literary sedition. He is not responsible for the fact that his work has been used to underpin and weaponize a larger, flawed Western narrative.

Nonetheless, Friday’s violent assault will once again be used to shore up a fearmongering narrative that empowers politicians, sells newspapers, and, if we can still see the bigger picture, rationalizes the West’s dehumanization of more than a billion people, its continuing sanctions against many of them, and the advancement of wars that fabulously enrich a tiny section of Western societies that continue to evade major scrutiny.

Hollow joke

Those elites have evaded scrutiny precisely because they are so successful at vilifying and eliminating anyone who seeks to hold them to account. Like Julian Assange.

If you think Assange brought trouble upon himself, unlike Rushdie, who is simply a hapless victim caught in the crossfire of a menacing “clash of civilizations”, it is because you have been trained – through your consumption of establishment media – into making that entirely unfounded distinction. And those training you through their dominant narratives are not a disinterested party, but the very actors who have most to lose should you arrive at a different conclusion.

In Assange’s case, there has been an endless stream of lies and misdirections that I and many others have been trying to highlight on our marginal platforms before we are algorithmed into oblivion by Google and Facebook, the richest corporations on the planet.

As Melzer pointed out at length in his recent book, the Swedish authorities knew from the outset that Assange had no case to answer on sex allegations they had no intention of ever investigating. But they made a pretence of pursuing him anyway (and left the threat of onward extradition to the U.S. hanging over his head) to make sure he lost public sympathy and looked like a fugitive from justice.

Anyone who writes about Assange knows only too well the army of social media users adamant that Assange was charged with rape, or that he refused to be interviewed by Swedish prosecutors, or that he skipped bail, or that he colluded with Trump, or that he recklessly published classified documents unedited, or that he endangered the lives of informers and agents.

None of that is true – nor, more significantly, is it relevant to the case the U.S., aided by the U.K. government, is advancing against Assange through the British courts to lock him up for the rest of his life.

For Assange, the West’s much vaunted principle of free speech is nothing more than a hollow joke, a doctrine weaponized against him – paradoxically, to destroy him and the free speech values he champions, including transparency and accountability from our leaders.

There is a reason why our energies are so heavily invested in worrying about a supposed menace from Islam rather than the menace on our doorstep, from our rulers; why Rushdie makes headlines, while Assange is forgotten; why Assange deserves his punishment, and Rushdie does not.

That reason has nothing to do with protecting free speech, and everything to do with protecting the power of unaccountable elites who fear free speech.

Protest the stabbing of Salman Rushdie by all means. But don’t forget to protest even more loudly the silencing and disappearing of Julian Assange.

Feature photo | Graphic by MintPress News

Jonathan Cook is a MintPress contributor. Cook won the Martha Gellhorn Special Prize for Journalism. His latest books are Israel and the Clash of Civilisations: Iraq, Iran and the Plan to Remake the Middle East (Pluto Press) and Disappearing Palestine: Israel’s Experiments in Human Despair (Zed Books). His website is www.jonathan-cook.net.