NEW YORK — Lakota Sioux protesters blockading the planned route of a $3.8 billion, four-state oil pipeline won a short-term victory on Wednesday, when the project’s developer, Energy Transfer Partners of Dallas, agreed to halt construction near the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota for at least a week.

“The decision was made at this time to have the pipeline company workers pull out, for the safety of everybody,” Morton County Sheriff Kyle Kirschmeier told journalists. “They’ll stop until we can get this resolved.”

The hiatus, which follows obstruction of the project by three Lakota Sioux tribes and their supporters, will last at least until a federal court in Washington, D.C., hears a challenge by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, which seeks an injunction against federal agencies that approved the pipeline, on Aug. 24.

“We said that we wanted it in writing, and we wanted it in writing sent to Standing Rock Chairman Dave Archambault and the copy sent to us on the front line,” Joye Braun of the Indigenous Environmental Network told Democracy Now! on Thursday.

Before the stoppage, the protest site, called the Camp of the Sacred Stones, blocked the pipeline’s construction for almost a week.

Dakota Access LLC, an Energy Transfer Partners subsidiary, sought a restraining order against protesters on Monday. By Wednesday, Prairie Public Broadcasting reported the number of protesters had swelled to over 1,500, noting: “Native Americans from Wyoming, Colorado and as far as Oklahoma are pulling up by the busload.”

‘It will destroy their water and destroy their land’

The mobilization culminates months of work by Sioux activists to build national opposition to the pipeline, from pitching teepees on the lawn of the North Dakota Capitol to running 2,000 miles across North America.

“This run is really important,” Joey Montoya, a Lipan Apache from San Francisco, told MintPress News on Aug. 7.

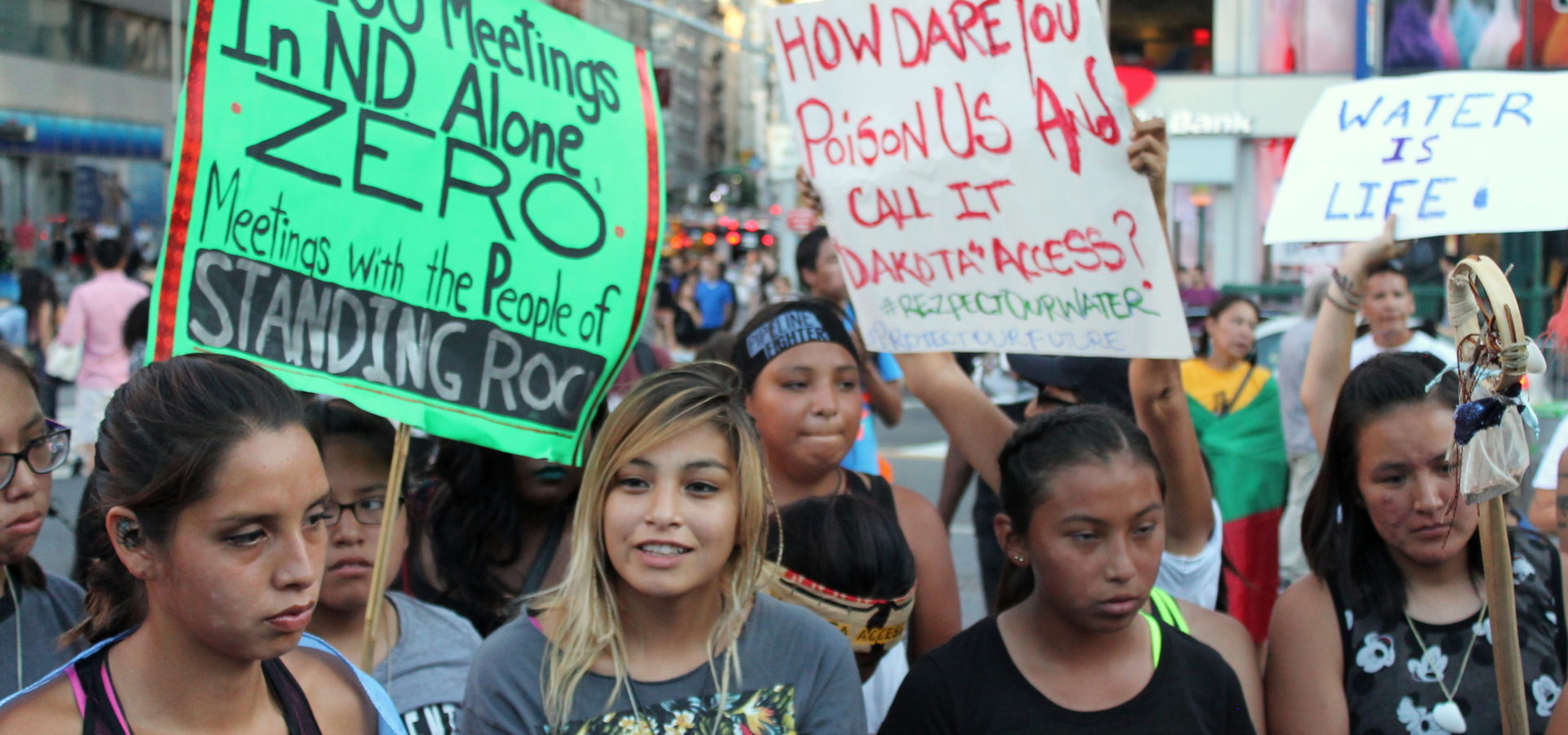

He spoke in New York’s Union Square as 200 supporters waited to greet 30 Sioux youth completing the final leg of a cross-country run protesting the pipeline.

Stopping in local communities to rally support along the way, they reached the White House before veering north to New York.

“The youth are running from North Dakota all the way to D.C. to deliver more than 140,000 petitions that were signed to say no to the Dakota Access Pipeline,” Montoya said.

“When it breaks, it will destroy their water and destroy their land.”

‘All pipelines break’

As the Lower Brule, Rosebud and Standing Rock Lakota tribes hold their positions in the project’s route, tribal protesters have asked supporters to keep signing the petition, whose signers have risen to nearly 190,000 as of Thursday afternoon.

To garner attention, tribal activists have solicited support not only from thousands along the route of their run, but also from celebrities like Leonardo DiCaprio and Rosario Dawson.

“What they’re doing is illegal,” Shailene Woodley told MintPress.

Along with Dawson and “Gasland” documentarian Josh Fox, the Golden Globe-nominated actress joined the runners at their final stop in Union Square.

“The tribe is suing our government because the Army Corps of Engineers failed to walk through the proper steps, according to tribal treaties,” Woodley said.

“It’s not a matter of if the pipeline breaks. It’s a matter of when. As we know, all pipelines break.”

‘This is the Keystone XL pipeline all over again’

Some have found the timing of the Dakota Access’ approval troubling, as it came just days before the Obama administration ordered an overhaul of the permit process.

“On July 26, the Army Corps of Engineers issued some major permits that will allow this pipeline to be built,” Bill Kitchen told MintPress.

A climate activist from Johnstown, New York, Kitchen attended rallies during the run in both Washington, D.C., and New York.

“One week later, the White House issued new guidelines for any federal agency,” he said.

“Before they approve a project like this, they have to do what they call a ‘climate test.’ They have to do an analysis of what this particular project will mean in terms of climate change.”

Kitchen compared Dakota Access to another proposal that received far more scrutiny.

“After the Army Corps issued the permits, it came out that two companies, Marathon of Texas and Enbridge of Canada, the largest pipeline company in Canada, have bought a 49 percent share in the Dakota Access Pipeline,” he said.

“They put down $2 billion. According to the reports in the financial news about this transaction, it’s going to move more tar sands out Canada. To me, this is the Keystone XL pipeline all over again.”

At 1,172 miles, Dakota Access would be just 7 miles shorter than the failed Keystone project.

And while President Barack Obama considered a “climate test” similar to the one he just imposed across the board before rejecting Keystone, Dakota Access faced no such hurdle.

‘We’re always at the front lines’

Aside from the environmental risks of the pipeline, many also hope to stem the social turmoil that has already accompanied development of North Dakota’s Bakken oil patch.

Over a recent five-year window, the oil formation’s production expanded from 200,000 barrels to 1.1 million barrels per day, making North Dakota the second-biggest oil producer in the country behind Texas.

During a similar period, the sudden influx of cash and outsiders fueled a 121-percent surge of violent crime in North Dakota’s Williston Basin, which includes Standing Rock.

“It’s like a tidal wave, it’s unbelievable,” Diane Johnson, chief judge of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation elsewhere in the Basin, told The Washington Post in 2014. “The drug problem that the oil boom has brought is destroying our reservation.”

Early Wednesday morning, Jon Eagle Sr., the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation’s tribal historic preservation officer, posted on Facebook that the threat of Dakota Access had partially restored an uncommon unity.

“The entire Oceti Sakonwin, Seven Council Fires of our Nation are in camp tonight but we are not yet united,” he wrote. “The last time the Seven Council Fires came together was June 25, 1876 at the Battle of the Greasy Grass.”

Montoya, who is now in the Camp of the Sacred Stones, warned that the fight unfolding there would ultimately affect everyone.

“Native communities are always just the first to be affected,” he told The Guardian. “We’re always at the front lines when oil companies come in.”