New York City’s divisive “stop-and-frisk” campaign seems to be on its last leg with the election of Bill de Blasio as mayor, who was an outspoken critic of the policy, so it’s likely he will name a new police commissioner and “stop-and-frisk” will become a gentler creature.

Back early August, federal Judge Shira Scheindlin ruled that the New York City Police Department was liable for a pattern and practice of racial profiling in its application of New York State’s “stop, question and frisk” law, for violating the Fourth Amendment protection from unreasonable searches and seizures and the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. In 2011, the NYPD reported 685,724 stops — a six-fold increase from 2002, when Raymond Kelly took over as police commissioner. With 84 percent of all stopped black or Hispanic, and with only 2 percent of all stops resulting in discovered weapons and contraband, the policy was perceived as being racist and oppositional to the city’s minority populations.

The court ruled in Floyd v. City of New York that despite receiving notice of widespread Fourth Amendment violations as a result of the NYPD’s stop and frisk practices, the NYPD repeatedly ignored clear evidence of unconstitutional stops and frisks, and deliberately maintained and escalated policies that resulted in more Fourth Amendment violations.

“Under the NYPD’s policy, targeting the ‘right people’ means stopping people in part because of their race. Together with Commissioner Kelly’s statement that the NYPD focuses stop and frisks on young blacks and Hispanics in order to instill in them a fear of being stopped, and other explicit references to race … there is a sufficient basis for inferring discriminatory intent,” the court said.

The city has tried to have Scheindlin’s decision postponed or put aside — particularly, in light of alleged misconduct from Scheindlin — in which the judge made comments to the media that suggested that she was not impartial to the “stop-and-frisk” cases she was assigned to (the Second Circuit’s Court of Appeals stayed Scheindlin’s ruling due to the conflict of interest).

A “stop-and-frisk” nation

But while “stop-and-frisk” is slowing to acceptable levels in New York City, elsewhere across the nation it is ratcheting up. In Baltimore, the American Civil Liberties Union has called on the Baltimore Police Department to acknowledge the large gap between the number of stops the department has conducted under its “stop-and-frisk” program and the amount of guns and drugs they are actually finding. “Our concern is that there’s been a wholly improper misuse of the tactic,” said Sonia Kumar, staff attorney for the ACLU of Maryland.

According to 2012 records, the police department made more than 123,000 stops, with only 494 searches conducted, ten incidents of drugs were found, nine guns and one knife.

There is the fear that the Baltimore Police is engaging in unjustified extralegal searches. More damningly is the fact that the Baltimore Police does not track its use of “stop-and-frisk,” allowing officers to use the tactic at their own discretion. “This has been an issue for more than half a decade and is a pressing concern for the agency,” said Police Commissioner Anthony Batts to CBS affiliate WJZ. He said he has since implemented long-needed reforms.

Baltimore has since stopped using the term “stop-and-frisk,” preferring to call their stops “investigative stops” in an attempt to escape criticism of the practice. “Whether we call it ‘stop and frisk’ or something else makes no difference to the Baltimore residents stopped and searched without any reasonable suspicion that they have done something wrong,” wrote Kumar in a statement after the announcement. “The problem isn’t the name – it’s how police are treating people.”

In Detroit, the long-standing practice of stopping “suspicious” individuals on the street is being defended — despite the Second Circuit’s ruling of unconstitutionality. “There has been no change,” said Detroit Police Chief James Craig. “I should remind the ‘public’ that we’re under consent judgment and part of that is that we adhere to the best policing practices. Any time we stop someone, certainly that stop is documented and is based on reasonable suspicion and is articulated in a report.”

In light of growing crime in the Motor City — where a deteriorating tax base and a lack of infrastructure development has led the city to bankruptcy, state oversight and a general sense of despair — the police department hired the Bratton Group and the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research — a conservative group funded in part by the Koch brothers who helped develop New York City’s “stop-and-frisk” program. The department paid the groups more than $600,000, suggesting that Detroit is seeking to institute NYC-style “stop-and-frisk” in a city that is 85 percent black.

“Based on reasonable suspicion, the Detroit Police Department is already a stop-and-frisk policing agency,” wrote Detroit Assistant Chief Erik Ewing in a statement to My FOX Detroit. “Detroit’s population is mostly African American, so it stands to reason that a high number of African Americans will be stopped, based on reasonable suspicion. This is not racial profiling, just officers doing good constitutional police work.”

“Terry v. Ohio”

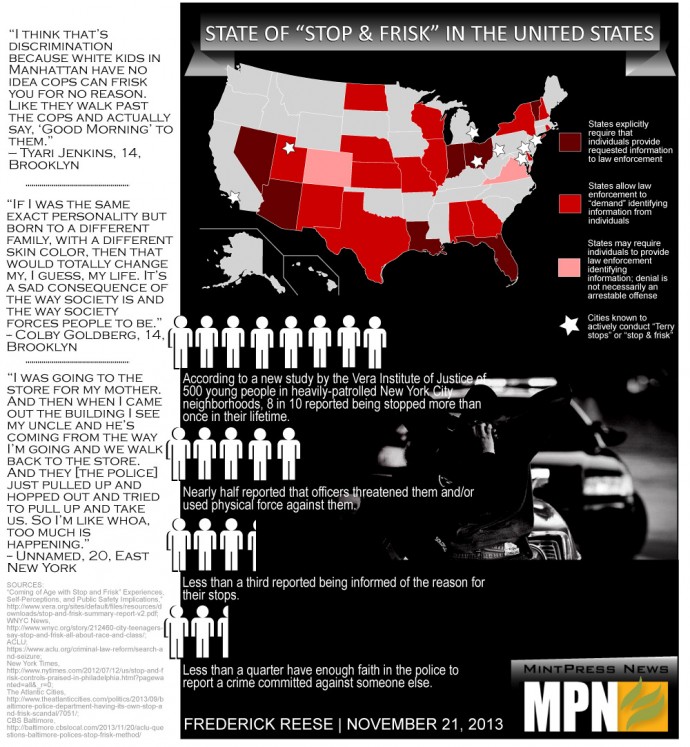

Since the 1968 Supreme Court case Terry v. Ohio — in which it was held that the police may stop a person if they have a reasonable suspicion that the person has committed or is about to commit a crime, and may frisk the suspect for weapons if they have reasonable suspicion that the suspect is armed and dangerous, without violating the Fourth Amendment prohibition on unreasonable searches and seizures — 24 states have integrated provisions permitting police officers to conduct “Terry stops,” or the stopping of an individual simply on the grounds of the officer’s suspicion with the intent of stopping an illegal act, and/or the requirement that stopped individuals must respond to police inquiries — including telling the stopping officer his/her name — into their police operating procedures.

Despite the wide swath of states that have these laws, typically, the decision to utilize the laws is left to individual police departments. An exception to this is Arizona, where the state’s newly-enacted “stop-and-frisk” law is being used to bolster the state’s crackdown on illegal immigrants. In most states that have this law, it is used as intended — as a rarely-used tool to stop and control a criminal situation.

But in a growing number of cities — including Los Angeles, Cincinnati, Salt Lake City and Pittsburgh — there has been a recent escalation of “stop-and-frisk” cases. In cities where there is no “Terry stop” law on the state level — such as Baltimore, Pittsburgh and Detroit — this recent growth represents these police departments assuming possibly discriminatory practices outside of their states’ consent.

Another way…

California does not have a “Terry stop” provision. Despite this, Oakland and San Francisco both considered an implementation of “stop-and-frisk.” San Francisco is currently witnessing an upswing in gun homicides, and since federal monitoring and multiple case settlements from the Oakland Police in regards to the “Riders” case — in which a band of Oakland police officers subjugated and targeted the city’s minority residents — the Oakland Police has proven to not have the resources to curb the city’s crime.

Even though both communities can make an argument for the need for “stop-and-frisk,” both rejected it, opting instead for targeted enforcement and community-oriented policing and building inroads to the cities’ communities. “The experiences of Philadelphia and New York City’s shows stop and frisk requires stopping an enormous number of men of color, undermining the trust and faith between law enforcement and those communities,” said San Francisco Board of Supervisors President David Chiu.

Recent research has shown that aggressive use of “stop-and-frisk” may be undermining the police mission to “serve and protect.” According to a September report from the Vera Institute of Justice, communities that are heavily-targeted by the police under “stop-and-frisk” grow to resent the police and distrust that police to the point that they would not seek help from them, endangering public safety. The Vera Institute surveyed 500 young people age 13 to 25 that live in such neighborhoods — with some having been stopped as many as 20 times by the police. “When asked to think beyond specific officers who had stopped them and to comment more generally on police in their neighborhood, the young people surveyed expressed critical views in most areas. In particular, only 15 percent believe the police are honest, and 12 percent believe that residents of their neighborhoods trust the police. Just four out of 10 respondents said they would be comfortable seeking help from police if in trouble.”

This also translates into a resistance to report a known criminal, to report a crime witnessed or known to have occurred, or to trust the police if they were the victim of a crime. In New York City, this is creating a situation where the percentage of serious crimes that are being solved is dropping.

The solution, oddly enough, may come from Philadelphia, which had a higher “stop and frisk” rate proportionately than New York, with 253,276 stops in 2009. But in recent years it has became a model for responsible use of the policy. A year ago, the city settled litigation by agreeing to install a number of safeguards on its “stop-and-frisk” program — including data collection on all stops and adequate training and supervision on stop administration. Since then, the number of stops has decreased. But as the homicide rate increased, it became obvious that “stop-and-frisk” is not inherently wrong and may even be needed but must be used responsibly.

“I think we have to face some realities,” said Philadelphia Police Commissioner Charles Ramsey. “We certainly do not want to be stopping people without the reasonable suspicion that we need to conduct a stop. But just because someone is complaining and they want to play the race card doesn’t mean it’s an inappropriate stop.”