If somebody you know got stopped seven or eight times for driving drunk, would you think they had a problem?

Texas lawmakers have now been popped by federal judges seven or eight times in recent years for intentionally discriminating against minority voters in voter ID and redistricting legislation.

Think they’ve got a problem?

The federal government has a program for repeat offenders like Texas; it’s called “preclearance,” and it forces states with histories of official racial discrimination to get their new election and voting rights laws checked by the feds — either the Justice Department or the courts — before those laws can go into effect.

Until the U.S. Supreme Court’s Shelby County vs. Holder decision in 2013, Texas was one of the several jurisdictions required to pre-clear new political maps and laws with the feds. It made a big difference. With preclearance, the presumption is that something’s wrong and the state has to take care to make sure no one’s rights are violated. Without it, the presumption is that the state knows what it’s doing and ought to be trusted until and unless someone finds fault with the state’s plans.

The federal Voting Rights Act has a “bail-in” provision that allows the courts to order serial discriminators back onto the preclearance list.

They haven’t done that to Texas, yet. The state argues that the federal judges finding intentional discrimination are wrong and that everything will be sorted out by the U.S. Supreme Court in due time.

In the meantime, the state wants to leave the laws that have been questioned in place, from the maps for the Texas House and the state’s congressional delegation to the state’s newest attempt to force voters to present an approved photo ID before they’re allowed to vote.

Related | Texas Backs Wisconsin In Battle To Protect Partisan Gerrymandering

The latest rulings say the lines of two of the state’s 36 congressional districts need to be redrawn, that the state’s voter ID law shouldn’t be used and that nine of the 150 districts in the Texas House are illegal.

U.S. District Judge Nelva Gonzales Ramos of Corpus Christi threw out the state’s latest voter ID law last week, saying it was “enacted with discriminatory intent — knowingly placing additional burdens on a disproportionate number of Hispanic and African-American voters.” She was reaffirming an earlier ruling and saying recent tweaks to the law didn’t cure it, and she also asked lawyers to file briefs arguing whether they thought the state should be subject to preclearance. The state is appealing the case, and it could end up in the Supreme Court. For now, however, the voter ID requirements are on hold.

The state’s redistricting maps, originally drawn after the 2010 census, have been litigated from their birth date to the present. Two recent rulings cite intentional discrimination in the state’s congressional and Texas House maps, and the three-judge panel in San Antonio that has been in charge of that case since 2011 is likely to either draw maps — or order them drawn — for two congressional and nine House districts within a matter of weeks. (On Monday, the U.S. Supreme Court put on hold the ruling that invalidated two of Texas’ 36 congressional districts.)

Those are just the most recent rulings. In these and related cases, the courts have found more than a half dozen times that Texas lawmakers have formulated election and voting laws intended to curtail the rights of the state’s minority voters.

Related | Citing Discrimination, Judge Strikes Down Latest Texas Voter ID Law

The courts are getting after lawmakers, in their way. But that also means they’re getting after them slowly, like telling a bobcat or a coyote that one of these days you’re going to make it stop tormenting the neighborhood’s backyard pets.

Only two more state elections will be held before the Legislature gets a new census, prompting the next scheduled round of redrawing political lines. Three elections have already been held — that’s more than half of the decade — under maps that the courts say are tinged with official racial discrimination.

The state might ultimately win in court. In that case, nothing needs repair. But if the state loses, and continues with the implicit aid of the courts to lose slowly, the effect will be the same as a win. The maps lawmakers wanted to remain in place will do so until the courts force a change. And the continuing noise about voter identification — what you need at the polls, what might happen if you do things wrong and so on — arguably continues to suppress the vote.

Without preclearance, a slow loss is a win for the state. If the courts order Texas back into preclearance, the state might hurry to set things right, perhaps shortening the number of elections held under what ultimately turn out to be unfair and unlawful laws.

Think of it as a sobriety test.

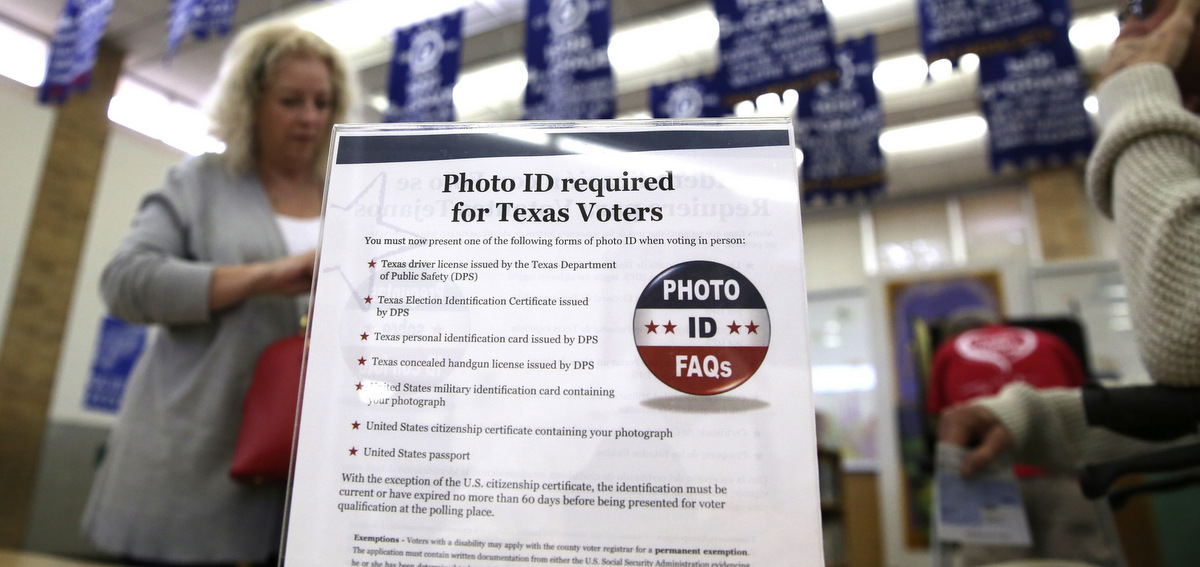

Top photo: A sign tells voters of voter ID requirements before participating in the primary election at Sherrod Elementary school in Arlington, Texas, March 1, 2016. (AP/LM Otero)

![]() The Texas Tribune is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 International License.

The Texas Tribune is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 International License.