In a recent child custody case, the U.S. Supreme Court seemed to side with a 3-year-old child’s adoptive parents over the legal claim of her biological father. One justice called it “heartbreaking.”

The case has raised eyebrows as some justices expressed skepticism in the ruling, which concerned a 1978 federal law intended to prevent the breakup of Native American families.

This law, called the Indian Child Welfare Act, was enacted in order to reverse centuries of forcible removal of Native American children from their homes in order to be assimilated into mainstream American culture. The recent ruling from the Supreme Court, however, may have weakened the law’s protection of Native American rights.

The case of Baby Veronica

A South Carolina court case known as Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl triggered a lof of media attention during the past few months, but according to the National Indian Welfare Association’s fact-check of various media reports on the case, there have been many inaccuracies.

In the case, Baby Veronica (now three years old) was placed for adoption by her mother in 2009. Her father, a registered member of the Cherokee Nation, was never informed by Veronica’s mother that she intended to place the child up for adoption. The child was adopted by Matt and Melanie Capobianco, a non-Native couple.

When the baby’s father Dusten Brown was served with adoption papers in 2010, he sought custody and won. He took the child home in 2011, where she has lived ever since. The Capobianco’s challenged this ruling, and the case worked its way up to the Supreme Court.

Brown’s lawyers argued his right to custody and invoked the Indian Child Welfare Act, a landmark law for the American Indian rights movement. That law sought to end the controversial practice of taking Native American children from their homes and placing them in foster care, thus loosening their connection to their families and culture. The federal Supreme Court sent the case back to South Carolina’s supreme court, but clarified the federal law in a way largely seen as giving the adoptive parents more legal heft.

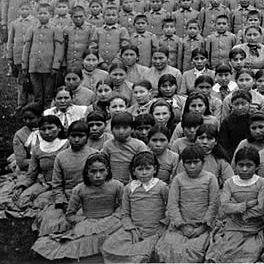

Boarding schools: oppression perpetuated

From the embryonic days of our nation, Native American tribes have struggled against the assimilationist policies of the U.S., which sought to destroy tribal cultures by removing Native American children from their tribes and families. In one stark example of such policies, the purpose articulated in a 19th-century-circa charter of the first boarding school in the Navajo Nation was “to remove the Navajo child from the influence of his savage parents.”

The federal government continued its boarding school policy for over one hundred years. “Countless lives give testimony to the harsh effects of that policy,” relays the Native American Rights Fund, an organization which provides legal representation and technical assistance to Native American tribes.

Authorities placed Native American children in these schools, which were established during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, to educate them according to Euro-American standards. The schools were first established by Christian missionaries of various denominations, but went on to be funded by the U.S. government, which saw the schools as a means to achieve assimilation of Native Americans, the prevailing policy at the time.

In these schools — which were in operation as late as the 1970s — children were underwent appearance changes like haircuts, were forbidden to speak their native languages, and even had their traditional names replaced by new European-American ones. The experience of the schools was often harsh: some children reported abuse and trauma at the hands of their teachers.

Ultimately, the children were encouraged — or forced — to abandon their Native American cultures and identities.

The Indian Child Welfare Act is a 1978 federal law that sought to keep Native American children with Native American families. Congress passed the ICWA in response to the alarmingly high number of American Indian children being removed from their homes by both public and private agencies. Lawmakers’ stated intent was to “protect the best interests of Indian children and to promote the stability and security of Indian tribes and families.”

SCOTUS neglects the importance of culture

In a 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court justices last month found major exceptions to the 1978 law.

The law “doesn’t apply in cases where the Indian parent never had custody of the Indian child,” wrote Justice Samuel Alito for the majority, joined by Chief Justice John Roberts, and Justices Anthony Kennedy, Clarence Thomas and Stephen Breyer.

“The Act would put certain vulnerable children at a great disadvantage solely because an ancestor — even a remote one — was an Indian,” Alito claimed. “A biological Indian father could abandon his child in utero and refuse any support for the birth mother — perhaps contributing to the mother’s decision to put the child up for adoption — and then could play his ICWA trump card at the eleventh hour to override the mother’s decision and the child’s best interest. If this were possible, many prospective adoptive parents would surely pause before adopting any child who might possibly qualify as an Indian under the ICWA.”

But many Native American rights advocates find the ruling troubling.

“In this case they overlooked the cultural aspects of this child, and baby Veronica, needing to know who she is, where she comes from, what her tribal ties are, understanding her heritage and her identity. And it’s unfortunate that this was lost … they seem to be much more focused on the rights of adoptive parents than on what is in the best interests of this Indian child,” says Mary Jo Hunter, a member of the Ho-Chunk tribe and professor specializing in Native American law.

I tend to agree with Hunter. This Supreme Court ruling runs the danger of following the same type of “we know better than you” logic that was responsible for centuries of racism and cultural degradation. Many of the subsequent problems faced by Native Americans, such as high suicide rates, poverty and ill health, persist in the present day.

“Statistical and anecdotal information show that Indian children who grow up in non-Indian settings become spiritual and cultural orphans. They do not entirely fit into the culture in which they are raised and yearn throughout their life for the family and tribal culture denied them as children. Many native children raised in non-Native homes experience identity problems, drug addiction, alcoholism, incarceration and, most disturbing, suicide,” the NARF reports.

Now is the time for the American legal system to take appropriate steps to granting Native Americans autonomy and true equality and to assist them in connecting to their cultures.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Mint Press News editorial policy.