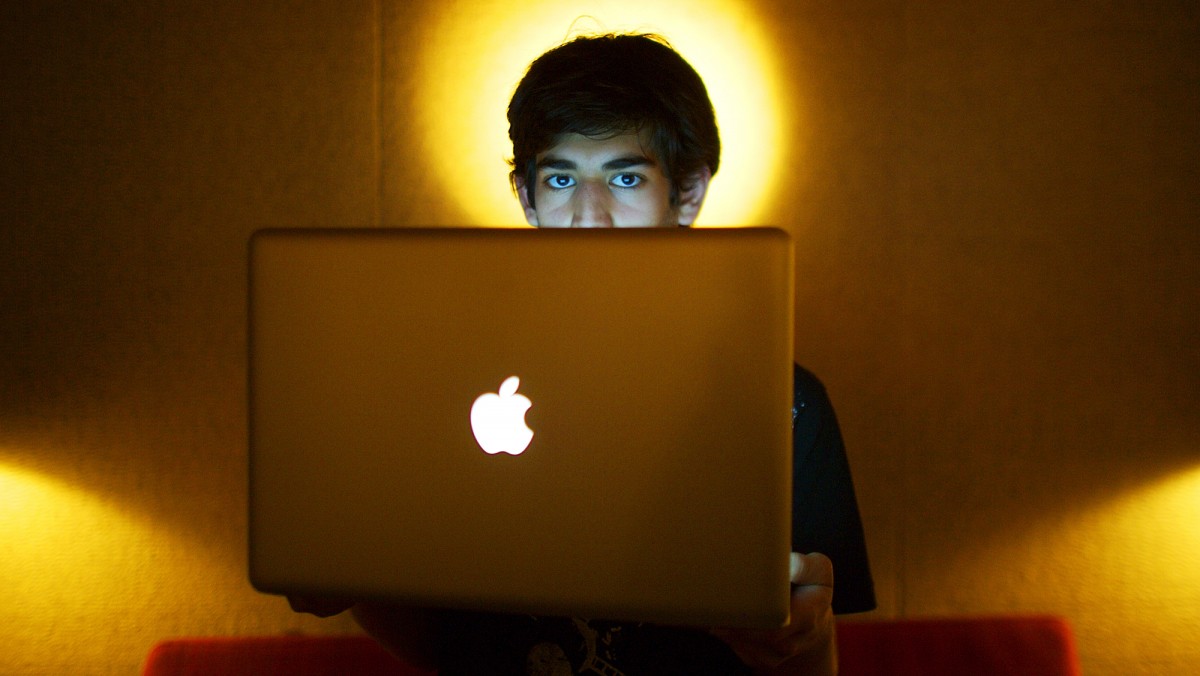

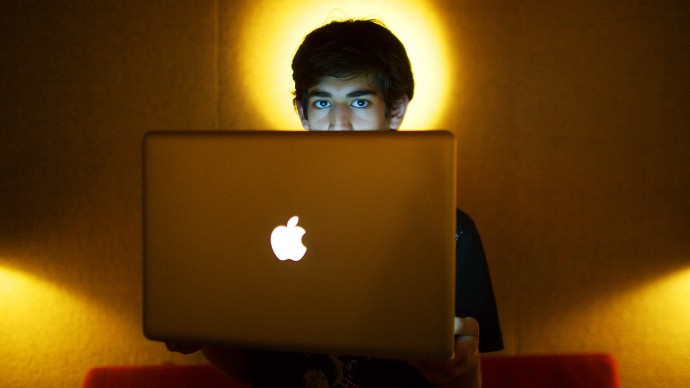

The death of Aaron Swartz has galvanized and changed the culture of the online community. Outrage about what is seen as an excessive and aggressive prosecution against the 26-year-old by the United States Department of Justice and his resulting suicide have convinced online freedom advocates to declare war against the notion of monetizing what should be freely-shared information and to honor a man that is now seen as a martyr for that fight.

Swartz was accused of inappropriately downloading academic journals and articles from JSTOR, an online journal distribution site. He attempted to do this anonymously from two laptop computers stashed in a maintenance closet and connected to the on-campus computer network at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Despite JSTOR not pressing charges, Swartz was charged with trespassing and user policy violations by the Justice Department.

Since his death, the charges have been dropped against Swartz.

Hacktivist group Anonymous has started a series of government website attacks protesting the federal government’s prosecution of Swartz:

“As his body is laid to rest, his image will be burned in our minds with a fire flaming out of control for justice and an apology from the Department of Justice. Days after his death, the DOJ finally dropped Aaron’s charges, something that should’ve been done when no true crime was committed and only free public documents were downloaded.”

Despite such protests, ultimately, the Swartz case is an indictment on the industry of selling information. The largest publisher of academic journals, Elsevier, posted 2011 revenues of €6.902 billion ($8.887 billion) and pre-tax profits of €1.09 billion ($1.403484 billion). The academic journal publishing industry represents a $25 billion a year industry, in which the costs are wholly absorbed by the end user.

As stated in TechDirt, “Scientific journals, as you probably know, are basically a huge scam. Unlike most publications, the journals don’t pay the people who provide all the material in those journals. Instead, the researchers pay the journals to publish their research. Not only that, but in exchange for paying the journal, the researchers also have to hand over their copyright on the research. This gets really ridiculous at times, as professors I’ve spoken with have needed totally redo their own experiments because some journal “owned” their research, and they couldn’t reuse any of the data.”

Stephen Curry, a structural biologist at Imperial College London, said that scientists need to come to a new, more equitable arrangement with publishers fit for the online age and that “for a long time, we’ve been taken for a ride and it’s got ridiculous. We face important policy choices on a whole raft of issues – climate change, energy generation, cloning, stem cell technology, GM foods – that we cannot hope to address properly unless we have access to the scientific research in each of these areas.”

Governmental repercussions and changes to the law

In a complaint letter dated Jan. 25 but published in the Huffington Post just last week, the attorney for Aaron Swartz formally filed a letter of complaint to the Office of Professional Responsibility about procedural misconduct regarding the lead prosecutor for United States v. Aaron Swartz, Assistant United States Attorney Stephen Heymann.

Swartz’s lawyer, Elliot Peters, accuses Heymann of withholding exculpatory evidence. Peters accuses the federal government of waiting a month to get a warrant to search Swartz’ computer and thumb drive. Heymann counters by stating he had no access to the hardware, which is why he needed to wait. However, an email from Jan. 7 from Michael Pickett, a Secret Service agent, to Heymann directly contradicts this.

Without a warrant, the computer and the data on it would have been inadmissible as evidence. The political backlash of this has — more or less — killed the hope for a judiciary posting for United States Attorney Carmen Ortiz, to whom Heymann reported.

In addition, two new laws have or will be introduced to the Congress in response to this case. The first, the Fair Access to Science and Technology Research Act (FASTR), introduced by Reps. Zoe Lofgren (D-Calif.), Mike Doyle (D-Penn.) and Kevin Yoder (R-Kan.) in the House and Sens. John Cornyn (R-Tex.) and Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) in the Senate, “require[s] federal agencies with annual extramural research budgets of $100 million or more to provide the public with online access to research manuscripts stemming from funded research no later than six months after publication in a peer-reviewed journal.”

This law is modeled on the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) privacy statement, which states that all final, peer-reviewed manuscripts must be made available to the public no later than 12 months after the official date of publication.

And this law is needed due to the economics of academics publishing. Public funding typically pays for the research done by members of the university communities who submit research to journals for publication and recognition from the scientific community. Many universities have to pay these journals to submit. The journals then send the research back out to other academics for blind peer-review (typically, pro-bono). Finally, the journal’s for-profit publisher sell back access to the published research to the universities’ library.

University libraries have struggled to keep up with the ever-growing costs of journals, which — from 1986 to 2004 — have grown 273 percent, four times the rate of inflation. The Harvard Faculty Council has issued a statement in regard to this situation:

“Harvard’s annual cost for journals from these providers now approaches $3.75M. In 2010, the comparable amount accounted for more than 20% of all periodical subscription costs and just under 10% of all collection costs for everything the Library acquires. Some journals cost as much as $40,000 per year, others in the tens of thousands. Prices for online content from two providers have increased by about 145% over the past six years, which far exceeds not only the consumer price index, but also the higher education and the library price indices. These journals therefore claim an ever-increasing share of our overall collection budget. Even though scholarly output continues to grow and publishing can be expensive, profit margins of 35% and more suggest that the prices we must pay do not solely result from an increasing supply of new articles.”

The second law, Aaron’s Law, is an one-page amendment to the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act — proposed by Rep. Lofgren — would make penalties for computer crimes proportional to the offense and decriminalize privacy policy violations.

As reported on the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s (EFF) website, “Creative prosecutors have taken advantage of this confusion to bring criminal charges that aren’t really about hacking a computer, but instead target other behavior prosecutors dislike. For example, in cases like United States v. Drew and United States v. Nosal the government claimed that violating a private agreement or corporate policy amounts to a CFAA violation. This shouldn’t be the case.”

“Compounding this problem is the CFAA’s disproportionately harsh penalty scheme,” the website continued. “Even first-time offenses for accessing a protected computer without sufficient “authorization” can be punishable by up to five years in prison each (10 years for repeat offenses), plus fines. Violations of other parts of the CFAA are punishable by up to 10 years, 20 years and even life in prison.”

Cindy Cohn, senior counsel to the EFF, has been working on the conception of Aaron’s Law. She believes that the changing nature of media usage in this country and on the Internet demands legislation to protect the users’ usage rights to purchased media. “Globally, we are shifting from a world where we buy and own things — in which the buyer has the right to do with the things he buys whatever he wants with them — to a world where we don’t own things, but license them. The things we use — including Internet access — have terms and limitations in which a person’s authority to use the product is based on. This is the position argued by the Justice Department.”

“The courts are starting to turn away from this argument,” Cohn continued. “The Ninth and Fourth Circuits have rejected this law, so a split in the Court is starting to form around this issue. The idea that misusing a website can be a felony strikes most people as extreme, and this is the reason this law must be changed.”

Jason Scott, spokesman for Archive Team, spoke of the importance of carrying on Swartz’s campaign against the monetizing of journals and scholarly articles: “I absolutely think that there been a concrete example — in Aaron’s death — that there are problems with the system in regards to papers and journal in how they move from publicly-funded research to pay-to-view distribution. This is not unlike Aaron’s involvement with PACER [Public Access to Court Electronic Records], in which buyers must pay for records they need for an adequate defense. This represents a problem.”

“The government has announced that publicly-funded articles will be released to the public eighteen months after publication for free,” Scott continued. “I have no doubt that this was due to Aaron. This case [the freeing of publicly-funded journals and articles], to Aaron, was akin to a single march from Dr. King or a single speech to a Chinese dissent; Aaron was so much bigger than this one thing.”

Archive Team, which archives documentation and online records that would otherwise be lost if a site or service online shutdown, has launched the Aaron Swartz Memorial JSTOR Liberator, which provides buyers with a bookmarklet that flags a journal to be downloaded and “liberated” for public use.

On JSTOR and MIT

A common misperception in the interpretation of the Swartz case comes in judging the liability of JSTOR, the online repository for which Swartz was arrested for illegally downloading journals. For the most part, JSTOR has little to do with the actual mechanisms behind this case, the rationale for downloading the journals or the federal prosecution.

JSTOR, an academic journal download site, works by purchasing journals from academic publishers to distribute to students and independent researchers. As mentioned, these journals can cost tens of thousands of dollars each, JSTOR offsets some of the acquisition costs with download fees for journals downloaded from its site. As JSTOR has little control over their costs in regard to purchasing journals and since JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization, JSTOR is — for the most part — a middleman in this argument.

Heidi McGregor is the vice-president for marketing and communications for Ithaka Holdings, JSTOR’s parent company. McGregor explained the relationship JSTOR has with its contributing publishers: “Our relationships with publishers have been built around the understanding that we provide access through libraries around the world. We would like to provide access directly to individuals, and are working with our publishers to figure out the best way to do so. Meanwhile, we have been able to collaborate with our publishers to make over 1,200 journals available for free, limited reading, and more new journals are becoming part of our Register & Read program every day.”

This is coupled by the fact that JSTOR had no part in the federal prosecution of Swartz — the case involved primarily violations of the MIT’s computer network user policy and the civil claim against Swartz by JSTOR was already settled by time the Justice Department started its investigation.

“We are saddened by the loss of such a gifted and talented person,” McGregor continued. “We do not know what Aaron intended to do with the copies of the articles he downloaded. Our focus throughout was to secure the content that was taken and ensure it was returned, which we did by virtue of a civil settlement with Mr. Swartz in June, 2011. It is not our role to determine whether Aaron committed a crime; the criminal case was brought by the government, and as has been widely reported, we had no further interest in the case once the content was turned over.”

MIT — who was the primary petitioner for the government’s prosecution — declined to be interviewed for this article. While MIT’s report on its involvement in this case is yet to be released, many already have blamed the school for its involvement in this case. At a March 12th memorial at MIT’s Media Lab, Aaron’s partner, Taren Stinebrickner-Kauffman, spoke of her frustration with MIT’s report: “I was hopeful that it could learn from mistakes made and make sure this injustice and tragedy is not repeated,” Stinebrickner-Kauffman told a several hundred people at the event. “I have since become less hopeful. I fear a PR exercise, a whitewash. The [MIT] general counsel is running this. Aaron’s lawyers and father have not been interviewed and there is no sign that the report will be released.”

“MIT called in the Secret Service when it could have handled the issue internally. When people called on them to drop the case, MIT refused. MIT helped the prosecution while it refused to provide access to the defense,” she said.

MIT hosted the event at the bequest of the MIT Media Lab Director Joi Ito — the school itself was not involved with the memorial.