WASHINGTON — In his eighth and final State of the Union address, President Barack Obama made an impassioned plea against religious bigotry and sectarianism. Keen to underscore his commitment to social cohesion and tolerance, he rejected “any politics that targets people because of race or religion.”

Referring to past fears and lapses in judgement U.S. society experienced in the face of “wars and depression, the influx of new immigrants, workers fighting for a fair deal, movements to expand civil rights,” Obama noted: “We did not, in the words of Lincoln, adhere to the ‘dogmas of the quiet past.’ Instead we thought anew, and acted anew.”

Though perhaps a powerful call against racism and bigotry, it ignores the grim realities of U.S. foreign policy. Explaining that his speech “essentially exemplified America’s exceptionalism,” Vanessa Beeley, an investigative journalist and expert on military maneuvering behind a veil of humanitarian assistance, noted: “His statement stands [as] a reminder of America’s double-standards and political posing.”

“If the White House still wants to claim the moral high ground, its ties with some of the world’s most repressive and reactionary regimes in the world — Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Bahrain, Qatar — have somewhat eroded any assumption the public might have as to the U.S. position vis a vis human rights and, of course, democracy,” Beeley told MintPress News in an interview.

Saudi Arabia’s “special friendship” with the U.S., as officials have been keen to highlight over the years, has allowed for U.S. officials to pick and choose when to show outrage and when to denounce human rights violations, manipulating international law to the tune of their own political agendas, rather than objectively defending the rule of law. And, in perhaps the most ironic turn of events in the world looking the other way on Saudi human rights abuses, the kingdom was given a chair on the United Nations Human Rights Council in 2013.

Despite Obama’s open rejection of bigotry, it would appear that Washington has blanketed Riyadh under its own exceptionalism — all in the name of economic pragmatism. Indeed, the nations’ interests are so intertwined that Saudi Arabia remains instrumental to U.S. economic stability through the petrodollar system.

The petrodollar system that was created in the 1970s has served America well, both economically and politically. What began as a way to drive more demand for the U.S. dollar in the wake of a move away from the international gold standard in 1971, it’s provided benefits that few could have ever imagined, including the solidification of the U.S. dollar as the global currency of choice. This was important, especially following a temporary loss of dollar credibility after President Richard Nixon’s decision to close the gold window.

This “dollars for oil” system has greatly enriched the nation. But this national prosperity has come at the expense of other nations and their potential prosperity, notwithstanding America’s moral credibility in the world over its selective blindness to Riyadh’s human rights violations.

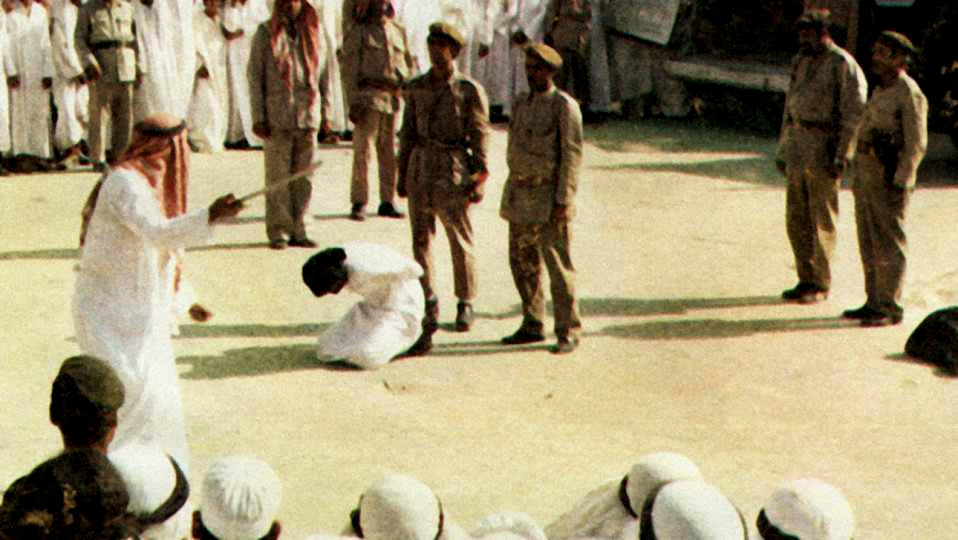

Such selective blindness was recently highlighted by Washington’s silence over the beheading of Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr in Saudi Arabia on Jan. 2. He was among the victims of Saudi Arabia’s campaign to execute 47 “terrorists,” including by beheading and death by firing squad, in the country’s largest mass execution in decades.

‘The most violent and abusive of all autocracies’

A pivotal figure for peaceful resistance in Saudi Arabia, Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr, a man of letters who reinvented himself as a human rights defender in the face of the suffering of his community in the eastern Saudi province of Qatif, was arrested in 2012 for speaking out against the House of Saud. Following a brutal police pursuit and arrest in which he suffered gunshot wounds, Sheikh al-Nimr was sentenced to death on charges of sedition, disobedience and bearing arms.

Ali al-Ahmed, founder and director of the Institute for Gulf Affairs, a Washington-based think tank, emphasized that any and all critics of the Saudi monarchy are designated as terrorists. Under Saudi law, any remark made against Riyadh can be construed as treason or domestic terrorism against the king, and is therefore punishable by death.

“The kingdom has relied heavily on violence and repression against rights and political activists to prevent its rule from being challenge. Saudi Arabia remains the most violent and abusive of all autocracies,” al-Ahmed told MintPress.

Likewise, Amnesty International denounces Saudi Arabia’s systematic attack on freedom of expression in the following terms: “Torture, public execution, discrimination, intolerance for free speech, possible war crimes in Yemen – and the list could go on. Dozens of activists remain behind bars in the Gulf Kingdom, simply for exercising their right to freedom of expression and assembly.”

Beyond America’s moral paralysis, and Saudi Arabia’s gruesome taste for blood-letting, stands the disturbing exploitation of sectarianism to serve ever-more repressive imperialistic agendas in the Middle East. In perpetual fear of Iran, which is majority Shiite, the kingdom has played the sectarian card since 1979 to manipulate and assert its supremacy over the region. Keen to smite its enemy, the House of Saud never misses an opportunity to antagonize Iran through its oppression of its own Shiite communities, which make up as much as 20 percent of its population.

Speaking to MintPress, George Galloway, a former member of Parliament with a record as an outspoken critic of war, made a horrific comparison to illustrate how the kingdom operates: “Saudi Arabia and ISIL are rooted in the same ideology, following the same rationale, and abiding by the same methods of oppression.”

Galloway continued:

“The Saudis have a reputation for being ideological. Analysts and others often talk about Wahhabism and [a] kind of orthodox Sunni version of Islam that’s embraced widely in the kingdom, and they assume that this means that the kingdom has always been a place where intolerance is the official [line of the] state, and that especially the state encourages violence or enmity to be directed towards minority groups like Shiites and Sufis and others. This hasn’t historically been true. The Saudis have often sought to manage and balance competing forces, because they’ve been practical and pragmatic.”

Wahhabism: A schism made in Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia’s powerhouse, or rather, its monarchy — the House of Saud — has relied upon its support for Wahhabism to create legitimacy, basing its rule not on popular legitimacy as most states do, but on enforced dogmatism and fear.

George Galloway defined al-Saud’s relationship to power as one anchored in terror and division:

“Imperial powers project their rule by inspiring and generating fear, fear of oppression and fear of what would befall society should it rebel against the Establishment. In Saudi Arabia it has manifested through a brutal crackdown against political dissidence and the criminalization of religious minorities: Shia Islam being on top of the list.”

Elaborating further on Saudi Arabia’s political and religious paradigm, Galloway noted how eerily similar al-Saud’s anti-Shiite narrative has been to that expressed by Daesh (an Arabic acronym for the group commonly known in the West as ISIS or ISIL), al-Qaida, the Nusra Front and Boko Haram.

“Wahhabism is at the rootcore of the radicalism movement which has swept across the Middle East and has now infected like a virus Western nations and beyond, other continents,” he said.

Wahhabism is a school of thought which emerged in the 18th century under the impetus of Muhammad ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab, a scholar who sought to revive the concept of takfir (apostasy) to promote his personal ideology. His alliance with al-Saud tribesmen eventually allowed for the Hejaz, Saudi Arabia’s western region, to became a playground for al-Saud royalty and whetted the new regime’s appetite for imperialism.

In 1802, Wahhabi legions ransacked the holy city of Karbala, which was then under the rule of the Ottoman Empire. They massacred an estimated 4,000 civilians, including women and children. Because Shiite Islam rose in denunciation of the ideology of takfir, a concept which is forbidden in most schools of Muslim thought, all Shiites were declared enemies of Islam.

Two centuries on, al-Saud and Wahhabism’s intolerance of Shiite Islam and all other Islamic denominations, including Sufis and Alawites, has metastasized, polluting all aspects of life. It is the institutionalization of persecution made in Saudi Arabia.

“Wahhabism, which is not to be confused with Sunni Islam, or Islam in general, stands behind the criminalization of Shia Islam in the kingdom and more broadly its demonization throughout the world,” Ali al-Ahmed, of the Institute for Gulf Affairs, said, adding:

“Over the years those negative feelings against Shiites materialized in the demonization of Iran as a sovereign political entity. Saudi Arabia’s rejection and hatred of Iran is rooted in sectarianism, more than it is political. And because Riyadh has billions of dollars to spend in championing its narrative, … unfortunately, it is this rhetoric which has been carried across the Middle East. As a result, Shiite communities have suffered a great injustice.”

Sheikh al-Nimr was denouncing this type of hatred and bigotry when the Saudi authorities moved to silence him. Sometimes compared to Gandhi, Sheikh al-Nimr called for peaceful change and social cooperation beyond matters of faith and ethnicity.

Recalling his father’s words, Mohammed al-Nimr, Sheikh al-Nimr’s son, told MintPress, “The roar of the word is mightier than the sound of the bullet.”

He added: “My father never promoted violence, only justice and resistance against oppression.”

“Sheikh al-Nimr was a holy man, a freedom fighter whose voice and democratic message carried far outside the kingdom,” journalist Vanessa Beeley said. “The Riyadh regime has worked to sully his name and his attempt to unify Saudi society and beyond the Islamic world by reclaiming Islam pluralist tradition.”

Resistance in the Hejaz

Sheikh al-Nimr came from a long tradition of human rights activists: His father and grandfather both campaigned for their people’s rights in Qatif. But his rise to international prominence came in 2011 during the “Arab Spring,” a grand democratic movement that swept across the Middle East and Northern Africa, threatening to forever alter the region’s political map through the deposition of autocracies.

An absolute theocracy, Saudi Arabia stood to lose everything, and so a grand crackdown was launched. The violence rocked Qatif hardest. Writing for the Brookings Institution earlier this month, Tamara Cofman Wittes explained that Sheikh al-Nimr’s 2012 arrest “was meant not merely as a signal to Tehran, but at least as much to Saudi Arabia’s own Shiite minority.” She explained:

“Shiites comprise as much as 20 percent of the Saudi population, and are concentrated in the oil-rich Eastern Province—and the community has regularly erupted in protests against its economic and political marginalization. In 2011, amid the Arab Spring uprisings in majority-Shiite Bahrain, Saudi Shiites also demonstrated for the release of long-held prisoners, and Saudi forces shot and killed several Shia in the streets.”

Although Shiites have long suffered at the hands of al-Saud, the media has rarely taken note. Indeed, as George Galloway pointed out, the mainstream media’s major shareholders happen to represent al-Saud’s interests: “Look at Channel 4 in the UK, Sky News or the Sun — they are all owned partly by Prince Waleed bin Talal, one of Rupert Murdoch’s best friends and investors.”

Scott Bennett, a former U.S. Army Special Operations officer, who served as a counter-terror analyst under the Bush administration from 2003 to 2008, said Riyadh has managed over the years to poison global viewpoints through the promotion of its own bias toward both Shiites and Iran.

“Anti-Shiism has been lumped to anti-Iranianism, and it is this analogy of a faith to a political entity which has defined U.S. foreign policy,” Bennett told MintPress. “Logically, Iran would be a natural ally of the U.S., while Saudi Arabia stands in negation of all American values. Yet it is Riyadh [that] U.S. officials have fawned over and shielded from international criticism.”

Scott Bennett described Washington’s ties with Riyadh as not simply dysfunctional but inherently intractable due to a phenomenon of economic and military codependency. Bennett argued that beyond a simple lack of political courage, the U.S. is now an economic hostage of al-Saud. If the U.S. were to go against Saudi Arabia, it risks unleashing a potentially catastrophic oil war.

From torture to socio-political discrimination, random arrests and unlawful imprisonment, there is no humiliation or injustice Riyadh has spared its Shiite communities. Worse still, such sectarian venom has spread throughout the region, infecting and painting nearby nations with a shade of fascism.

The Shiites of Saudi Arabia have been classified — through the social, political and religious spheres — as second-class citizens. The Shiite minority is largely concentrated in Eastern Province. The vast majority of Saudis are Sunni Muslims, many of whom adhere to the rigid Wahhabi ideology, which in principle is extremely anti-Shiite. Disdain for Shiites is apparent in religious publications under the government and school materials, and many Saudi government clerics are brazenly outspoken on this point.

One prominent cleric in Saudi Arabia, Mohammed Al Arifi, delivered a speech stating: “Today the evil Shiites continue to set traps, for Monotheism and for the Sunnis.” He further claimed that all Shiite loyalty is to Iran and that Shiites wish to do violence against Sunnis “because their name was Omar or Aisha,” and that Shiites would “skin Sunnis and boil them in water.”

“The homogenization of Shiites reflected in these claims would seem outrageous to an academic or anyone with experience interacting with Shiites. However, many Saudis believe this discourse and have been indoctrinated with a deep hate for Shiism, although the majority have little to no interaction with Shiites,” noted Arzu Merali, co-director of the Islamic Human Rights Commission, to MintPress.

Western complicity and hypocrisy

For a glimpse of the political selectiveness of the West, compare the silence on Sheikh al-Nimr’s beheading to the grandstanding on Madaya. The Syrian town was purportedly starved by the government in Damascus, but it had actually been besieged by radical militants affiliated with the Nusra Front, an al-Qaida affiliate in Syria, and Daesh — both Wahhabi-inspired outfits.

Beyond the clear “agenda” behind this media campaign — the further vilification of Syrian President Bashar Assad — it appears evident Western media has become an echo-chamber for House of Saud propaganda and its agenda in the region.

Western powers’ hypocrisy in the case of Sheikh al-Nimr did not go unnoticed. Amnesty International UK’s Shane Enright said at a rally outside the Saudi embassy in London: “This [execution of Sheikh al-Nimr] is an absolute, fundamental, breach of basic human rights,” pointing to a recent Amnesty report which concluded that the trial against Sheikh al-Nimr was “deeply flawed.”

“We also came to the conclusion that he was jailed solely for expressing his peaceful points of view, protesting peacefully against the regimes,” he added.

Maya Foa, director of the death penalty team from Reprieve, a U.K.-based International human rights organization, slammed the British and U.S. governments for supporting their ally Saudi Arabia, noting they “must not” turn a blind eye to the executions.

“Saudi Arabia’s allies – including the U.S. and U.K. – must not turn a blind eye to such atrocities and must urgently appeal to the kingdom to change course,” she told the press.

While Sheikh al-Nimr’s voice was silenced by the swing of a sword, the resistance movement he came to embody was offered a new catalyst. In death, his message is resonating with more intensity, transcending those barriers the House of Saud has worked so diligently to erect to protect their rule.

In Qatif, a community far from being broken, people have drawn strength from Sheikh al-Nimr’s courage, determined to stand a tide together against autocracy. Beyond Qatif, in Yemen, India, Pakistan, Iran, and elsewhere, demonstrations erupted solidarity for Sheikh al-Nimr, signs that resistance is no longer just an idea, but a movement.

“Because it is in our nature to resist, Saudis, and more specifically Saudis in Qatif, will push against the unjust rule of al-Saud monarchy, so that their freedom is reclaimed. Whether Western powers are there to support or oppose them will determine which names history will make infamous,” concluded Vanessa Beeley, the investigative journalist.