NEW YORK — Donald Trump’s presidential campaign rhetoric was a cocktail of ostensibly nationalist economics and isolationist foreign policy that was viewed by much of the punditocracy as a sharp break from traditional U.S. policy. But while his words seemed to be filled with promise, his actual policies have, rather predictably, shown themselves to be hollow.

While the corporate media and Democratic Party apparatchiks have been foaming at the mouth about Russia’s role in torpedoing Hillary Clinton, few have bothered to examine the deeper political and economic motivations and policies underlying the Trump doctrine. In doing so, it should become apparent that rather than significantly breaking from the hegemonic worldview of previous administrations, Trump and his coterie of generals and strategists intend to use the same sorts of coercion and force that have formed the bedrock of U.S. foreign policy for the better part of the last several decades.

Russia, China and Iran each pose unique challenges to the new administration. When seen as a bloc, they represent a significant obstacle to continued U.S. hegemony. However, a sober analysis must deal with existing political forces and their agendas, rather than the fanciful ideas that are the stuff of speeches and politically biased punditry.

Russia and the Slippery Politics of Oil

The corporate media has been all agog with every new revelation about President Trump and his administration’s ties to Russia: the alleged hacking of the election, the purported sex tape and clandestine meetings, to name a few. But while such stories are good for ratings, they invariably obscure the far more critical aspect of the story – economic, political and geopolitical imperatives.

Examined from these perspectives, it becomes clear that while Trump, Steve Bannon and others in the administration may have sympathetic feelings for Putin and the Russian government, their actions are dictated by interests, not friendship.

And what are those interests? First and foremost is the tens (or hundreds) of billions of dollars at stake for ExxonMobil, the largest oil company in the U.S. and longtime employer of Secretary of State Rex Tillerson. With such vast profits at stake, it’s no surprise that Trump’s administration supports the idea of easing or even lifting sanctions on Russia, having gone so far as to float a plan to lift the sanctions that would’ve used former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn as an intermediary.

But even if Trump doesn’t end the sanctions, it’s clear that he and Putin are on the same page when it comes to mutually beneficial economic arrangements in the energy sector. This raises questions about China and Iran, both of whom are major parts of the energy equation.

It was just three years ago, as the crisis in Ukraine was reaching a boiling point, that Moscow and Beijing signed a landmark gas deal worth at least $400 billion. At the time, many political and financial observers noted that the move was likely part of a broader effort by Moscow to shift away from its heavy reliance on energy exports to Europe, providing Putin with the leverage he might need to blunt any economic attacks by the U.S. and its European Union allies. But a number of factors have complicated Sino-Russian relations since then.

The collapse of global oil prices from 2014 to 2015 undeniably altered Moscow’s plans, as the major capital investment needed to build pipelines to China became more burdensome and less lucrative. Additionally, added price pressure forced Russia’s energy sector to further cement its ties with Western customers. This was perhaps best evidenced in the massive series of deals signed between Russia’s Gazprom and Royal Dutch Shell.

It seems Russia is attempting to play West against East, hoping to turn its energy muscle into political currency. As Moscow makes inroads with Beijing, it knows that major oil companies like ExxonMobil, Royal Dutch Shell and British Petroleum (BP) will remain major cash cows.

And then there’s the wild card: Iran.

Despite the apparent coincidence of agendas in Syria, Moscow and Tehran are not on the best terms — and energy exports are at the root of their mutual distrust. With the July 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action nuclear agreement signed by the P5+1 countries, Iran effectively took its first step towards full economic normalization with the West. While there are many industries and markets that would be impacted by the deal, none figure more centrally to Western corporate designs than the energy sector.

As Bloomberg correctly noted in late March 2015 on the eve of the initial framework agreement which laid the groundwork for the negotiations in Vienna: “[Iran] is emerging again as a potential prize for Western oil companies such as BP, Royal Dutch Shell Plc, Eni SpA and Total SA. The Chinese can also be expected to enter the race, while U.S. companies, more burdened by sanctions and legacy, will be further down the pack…‘Iran is the big prize…The resource size is very attractive.’”

While U.S. oil companies like Exxon-Mobil and Chevron might have a difficult time penetrating the Iranian market, that shouldn’t be an issue for their European competitors, nor for massive Chinese oil companies like Sinopec and Chinese National Petroleum. Iran has effectively become a competitor with Russia both for exports westward to Europe and eastward to China.

This dynamic makes for an interesting contrast between diplomatic rhetoric and political posturing and cold, hard economic and geopolitical strategy. The tension has spilled over publicly numerous times — perhaps most notably in the summer of 2016, when Iran publicly revoked Russia’s rights to use the Hamadan base in western Iran after Russia publicly bragged about the deal with Tehran in an attempt to show that its footprint in the region was widening.

To illustrate what kind of danger Russia sees in Iran, one only needs to look at a February announcement stating that the former Soviet republic of Belarus, a country intimately connected to Russia, had signed a lucrative energy import deal with Iran. This comes on the heels of Poland similarly replacing Russian oil with Iranian oil.

Considering the one-dimensional nature of Russia’s economy – energy and weapons exports account for the majority of Russian exports and a huge proportion of its total GDP – a threat to Moscow’s position in global energy markets, especially in Europe, makes Iran as much an obstacle as an ally.

It is for this reason that Putin and his administration have been so cozy with Trump despite the possibility of U.S. military action directed at Iran. Any moves by the U.S. against Iran only bolster Russia’s position as a gas exporter to Europe and Asia, as well as making it seem more attractive to investors whose desire for political stability might sway them to look to Russia rather than Iran. Of course, instability is also good for Russia, as unrest in the Persian Gulf or the Strait of Hormuz means upward pressure on oil prices and increased revenue for Moscow.

China: The Economic Elephant in the Room

At the center of all geopolitical questions in the age of Trump is China. While Obama’s “pivot to Asia” was widely seen as recognition by the U.S. that China had become the principal geostrategic imperative for U.S. hegemony, Donald Trump has taken this framework and transformed it into his war cry. Throughout the presidential campaign, Trump portrayed China as a menace, a country “taking advantage of us” and a serial currency manipulator.

With much of the world focused on Trump, China has quietly positioned itself as a global leader in multiple areas, including climate change, green energy and global trade. China as the anti-Trump is undeniably appealing to many countries and corporations around the world. And within the sphere of geopolitics, Trump puts the much-touted Sino-Russian friendship to the test.

China and Russia have signed a raft of energy and weapons deals that have led many to believe China and Russia are close allies. However, there are undoubtedly experts in Beijing who are nervously eyeing their purported ally in the Kremlin.

One source of irritation for China is the perception by many Chinese that Putin and his oil oligarch allies simply use China for leverage against Europe and the U.S., and that the lifting of sanctions against Russia would likely mean a Westward pivot by Moscow.

While Moscow has attempted to cultivate greater business ties with China, it remains equally true that a full re-orientation of Russia’s economy toward the East is a monumental task that is unlikely to occur anytime soon. And though there was strong political pressure forcing such moves in 2014, with Trump in the White House, it seems those pressures have diminished.

Another area of political conflict between Moscow and Beijing that has been heightened by Trump’s right-wing politics is the fate of the European Union. Moscow has made no secret of its disdain for the EU, as the Kremlin tacitly or overtly backs every far-right, anti-EU political formation with any serious shot at political power.

These include Le Pen and the National Front in France, Norbert Hofer and Austria’s Freedom Party, Nigel Farage and UKIP and Geert Wilders and the Dutch PVV. Aside from far-right racist, xenophobic and Islamophobic politics, these leaders and groups have one thing in common – their opposition to the EU. In effect, Russia has become the state power behind the anti-EU push.

This is in direct opposition to China, which has repeatedly argued in favor of the EU in terms of maintaining its continuity, as well as genuinely opposing European destabilization. As Chinese Prime Minister Li Keqiang, in uncharacteristically blunt terms, stated in 2015 at the height of the Grexit crisis:

“Let me reiterate that China always supports European integration and that China hopes to see a prosperous Europe, a united European Union and a strong euro…the issue whether Greece stays within the eurozone not only concerns the stability of the euro, but also … the stability and economic recovery of the whole world.”

China has much at stake when it comes to Europe, where a single market is an absolute necessity for China’s long-term economic development goals. The Chinese vision of the near future revolves around the development of the One Belt, One Road (OBOR) strategy of infrastructure development throughout the Eurasian landmass, which links China by land and sea to the rest of Asia and Europe. This strategy requires the EU to remain the enormous single market that it is now, rather than a patchwork of smaller markets.

Herein lies the divergence of Moscow and Beijing’s interests. For Russia, a destabilization or eventual breakup of the EU strengthens its position, as individual European countries would be free to pursue energy at the lowest possible cost regardless of any political concerns.

There has already been some indication of this, with the far-right fascist allied government of Viktor Orban in Hungary cutting deals with the Russians against the wishes of many EU counterparts. Multiply this many-fold and you’ll get a sense of Russia’s vision for Europe.

For China, the EU is absolutely critical as a trading partner and unified market for Chinese goods. With the infrastructure development that is currently under way in Asia, Europe is increasingly being seen as a source to rival the U.S. market for China. Chinese tourism to Europe is growing rapidly as well. In short, China sees the EU as an ally, not an obstacle.

Similarly, China finds itself at odds with Russia over Iran. While Russia has postured as a friend to Tehran when it’s been politically expedient, there are few illusions in either country about the deep mistrust that still exists. China figures centrally in this triangle, as it remains in desperate need of energy imports.

As of now, China’s energy imports primarily come via tanker shipments, although that is rapidly changing. While Russia and China have signed deals for pipelines to bring Russian energy to China via both western and eastern routes, Iran may emerge as a counterforce that could potentially rival Russia for exports to China.

The Power of Siberia pipeline, which will bring Russian gas to China, is set to become fully operational later this year. The significance of this development should not be understated, as a cursory look at a pipeline map of Gazprom’s eastern projects demonstrates that the Power of Siberia project, along with the other pipelines already in place, will position Russia to be a major provider of energy to China and other east Asian countries via soon-to-be constructed gas facilities on the Sino-Russian border.

In addition to these important energy developments, the imminent construction and incorporation of the Altai Pipeline could make Sino-Russian energy cooperation into a full-blown energy alliance. Projected to supply 30 to 38 billion cubic meters of Russian gas from Western Siberia to China, the pipeline would cement Russia as China’s primary economic partner in terms of energy.

Russia would supply not only massive amounts of gas, but also be positioned in a strategically useful location, as the pipeline runs directly into northwest China’s Xinjiang Autonomous Region, which is the hub of many of China’s plans for its One Belt, One Road strategy. In this way, Russian energy will become a principal driver of Chinese economic development and expansion. More broadly, it will make Russian gas and Chinese production the twin driving forces of Eurasian integration.

Trump Seeks To Put Iran, China In Checkmate

However, the burgeoning Sino-Russian alliance started developing before Donald Trump and the promise of re-admittance to the club of Western powers. With Tillerson and Lavrov oiling each other up behind closed doors, China may be viewing the shifting political ground with extreme skepticism.

In the South China Sea, Russia has conspicuously avoided outright support for China. Russia is deeply worried about China’s One Belt, One Road development model, as it will effectively make China the dominant political and economic player in central Asia, territory that Russia has traditionally seen as being within its sphere of influence. Russia also sees both China and Iran as potentially major players in post-occupation Afghanistan, something that will further erode Russia’s geopolitical advantage in Asia.

So what does Trump have to do with these complex sets of geopolitical and strategic challenges? Perhaps it would be better to ask what Trumpism, such as it is, represents. Aggression against Iran and China with a charm offensive aimed at Russia represents the visible part of the U.S. iceberg. But below the surface, past the rhetoric of multipolarity and decentralization of global power, there is a realignment of political forces on what Zbigniew Brzezinski called the “Grand Chessboard.”

Russia, China and Iran each represent different obstacles for the Trump administration and for the U.S. empire. The next few years will see a further shifting of alliances as Russia and Iran compete for energy markets, Iran and China grow closer together and the Russia-China honeymoon turns sour as Putin wines and dines with executives from Western oil companies.

Russia is not the bogeyman that the mainstream press depicts it as, nor is it the innocent victim that its own state-controlled media portrays. Rather, Russia is a country guided by its perception of its interests, as are China and Iran. The fiction is that these interests are shared. They certainly are not, at least much of the time. And it is those contradictions and points of friction that the U.S. will seek to exploit in the age of Trump.

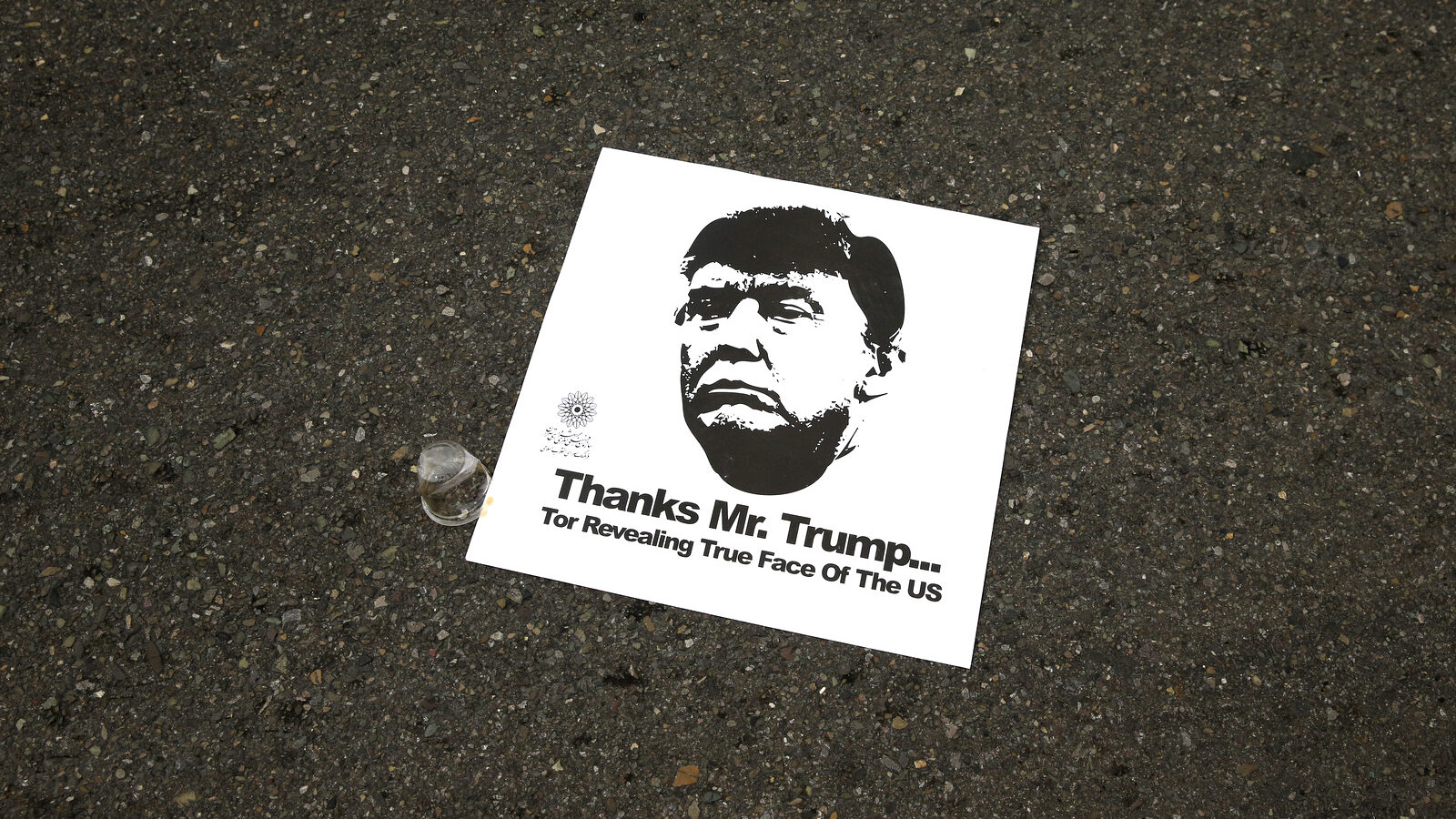

Feature photo | A poster on the street with a portrait of U.S. President Donald Trump and a sentence referring to a quotation of Iranian Leader Ali Khamenei in Tehran, Iran, Feb. 10, 2017. (AP/Vahid Salemi)