The creeping use of counter-terrorism policies in Britain to clamp down on civil liberties appears to be relying on a number of flawed assumptions. Not content with the stigmatizing of Muslim communities, the U.K.’s spot the terrorist approach also has the potential to criminalise political activists and campaigners by labelling them with impossible-to-define terms such as non-violent extremist or domestic extremist.

Prevent is one strand of Britain’s counter-terrorism strategy which has had various mutations since the terrorist attacks in London on July 7, 2005. The most recent and controversial addition to the widely discredited strategy has been the statutory duty placed on every local authority, educational institution, and NHS Trust — plus the police and Prison Service — to report those suspected of being “drawn into terrorism.”

Sound scary? It is.

As a result, multiple organizations have formed the Together Against Prevent campaign to express their opposition to the damaging methods, which rely on a tangled web of vague definitions to allegedly counter radicalization.

Earlier this week, the names of seven primary school pupils — “feared to be at risk of radicalisation” — were inadvertently revealed by an east London primary school. The names were revealed after a parent submitted a Freedom of Information request asking if certain children had been targeted.

The response to that parent from the school included the line:

Our project will combine a universal teaching module with a range of tools designed to ensure early intervention for any children who are felt to be vulnerable to radicalization.

Child protection officials have also been criticized for warning parents that young people who take issue with government policy or question what they are told in the media may have been radicalized by extremists. A leaflet distributed by an inner-city safeguarding board as part of an anti-extremism drive lists these signs as specific to radicalization:

- Out of character changes in dress, behaviour and changes in their friendship group

- Losing interest in previous activities and friendships

- Secretive behaviour and switching screens when you come near.

- Owning mobile phones or devices you haven’t given them

- Showing sympathy for extremist causes

- Advocating extremist messages

- Glorifying violence

- Accessing extremist literature and imagery

- Showing a mistrust of mainstream media reports and belief in conspiracy theories

- Appearing angry about government policies, especially foreign policy

Once a young person has been “identified as being vulnerable to being drawn into terrorism,” they are referred to the Channel programme. Recently released figures reveal that eight people a day are referred to the controversial programme — as part of the Prevent strategy.

A social care worker who works with young people with learning disabilities told Anti-Media that it is mandatory for staff within her organization to take the Channel General Awareness course. “Certificates of completion of the course go on all staff files,” she said.

After completing the 25-minute course, the website boasts that participants should be able to explain:

- How Channel links to the government’s counter-terrorism strategy

- Describe the Channel process and it’s purpose

- Identify factors that can make young people vulnerable to radicalisation

- Define safeguarding and risk ownership of the Channel process

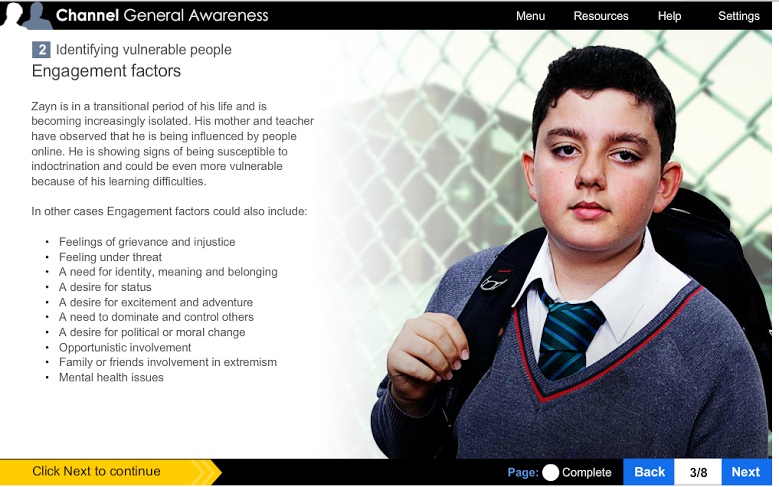

By using early intervention to “protect and divert people away from risks of being drawn into terrorist activity,” the Channel course relies on a number of highly dubious case studies to help participants identify risk factors for those vulnerable of being “drawn into terrorism.”

This little device delivers turnkey Internet privacy and security (Ad)

The first case study is Zayn, who is becoming increasingly isolated and spends a lot of time online.

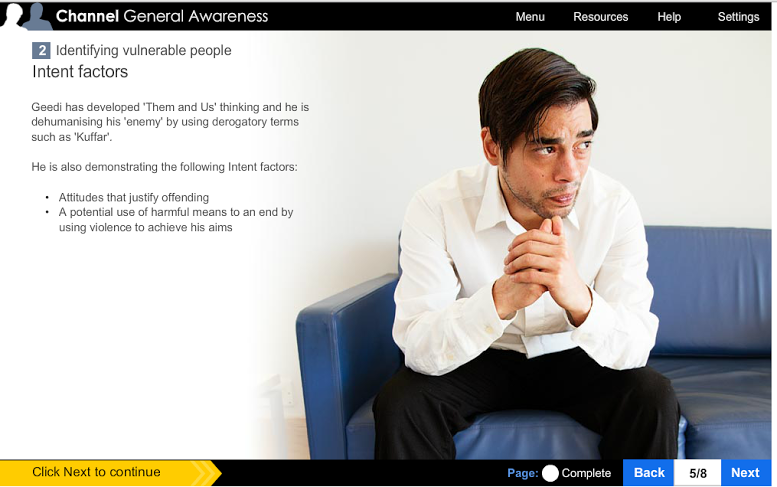

The second is Geedi, who has developed “them and us’’ thinking.

The second is Geedi, who has developed “them and us’’ thinking.

Callum’s anti-establishment views, mixed with mental health issues, show he “has reasons for intent to involve himself in terrorism.”

Callum’s anti-establishment views, mixed with mental health issues, show he “has reasons for intent to involve himself in terrorism.”

If workers are merely undertaking an online 25-minute course, the alarming reports concerning how the Channel programme is being used and the way referrals are made come as no surprise.

If workers are merely undertaking an online 25-minute course, the alarming reports concerning how the Channel programme is being used and the way referrals are made come as no surprise.

These reports, of course, tell us nothing of the negative qualitative effects on British families who are subjected to unwarranted intrusions into their private lives; or how the teaching, health, and caring professions are effectively becoming an arm of the security services.