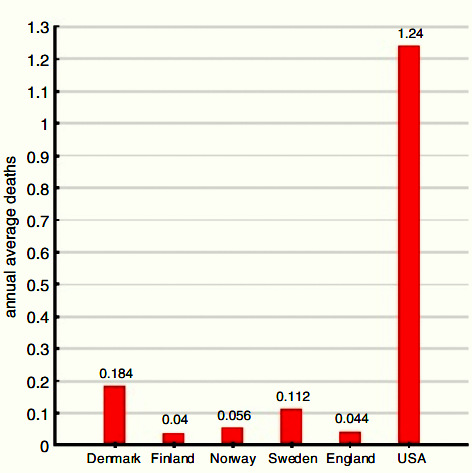

WASHINGTON — Matthew Ajibade, Roberto Ornelas, and Garrett Gagne: These were the first three people killed by American police this year. Since their deaths at the hands of police on Jan. 1, police have killed another 687 people, averaging three daily, according to The Guardian’s “The Counted,” currently the most comprehensive database of killings by U.S. police.

This stands in sharp contrast to police in Norway. They fired guns twice last year. And Norwegian police haven’t killed anyone since 2006, and that police-related fatality was the only one that year.

Of the 34 countries belonging to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, an economic organization committed to democracy and a market economy, Norway is one of just four countries which routinely deploy unarmed police. Norwegian police have access to firearms, which are locked in patrol cars, but they cannot use them without authorization from a higher authority.

When Anders Behring Breivik, the right-wing extremist who killed 77 people and injured 241 others during a killing spree at a Workers’ Youth League summer camp in 2011, police only fired one time, according to a report released by Norwegian police last week.

The country also has a low prison rate, with less than 4,000 of its 5 million citizens in jail, and low recidivism rates.

The United States, on the other hand, is home to the world’s largest prison population. Roughly one in every 100 American adults is incarcerated. Recidivism here hovers above 76 percent.

How can the situation with police be so different in these two countries?

‘What can the Scandinavian experience teach us?’

A 2014 case study found that police department policies have a greater impact on how often a police officer uses his or her weapon than whether the officer even has a weapon in the first place.

Ross Hendy, a New Zealand police constable and PhD candidate at the University of Cambridge, authored “Routinely Armed and Unarmed Police: What can the Scandinavian experience teach us?,” a study which focused mainly on Norway and Sweden.

Hendy found that officer safety might be jeopardized when officers are routinely armed because armed officers more likely to engage in dangerous situations, yet departmental policies were of greater importance to influencing how officer behavior, particularly in tense situations.

To illustrate how this works, he used the image of a police officer pointing a gun at a criminal suspect, inviting the reader to imagine what would be going on inside that officer’s mind.

He wrote: “One might consider that an officer staring down the barrel of a gun may not necessarily factor in the subtleties of whether a warning shot is appropriate, or whether it would be best to shoot for the leg or chest, especially in a critical incident.”

In this case, he was comparing Norway with other Scandinavian countries whose police are routinely armed — notably, Denmark, Finland and Sweden. He found that even when Norwegian police are armed they threaten to shoot at a rate far higher than the other countries. He attributes this to federal policy.

Hendy wrote:

“In other words, when considering the impact of routinely arming a routinely unarmed police force, these data show us that it is more likely that departmental policies will have a greater effect on the police officer’s decision-making process than whether the officer is routinely armed or not.”

‘Not better, just less’

Indeed, it is because of historically repressive policies that police in the U.S. kill an average of three people each day, the country is home to over 2 million prisoners, and almost 5 million people are currently on parole or probation, argues Christian Parenti, a professor in the Global Liberal Studies Program at New York University and author of “The Soft Cage: Surveillance in America from Slavery to the War on Terror.”

“At its heart, the new American repression is very much about the restoration and maintenance of ruling class power,” Parenti wrote in a recent article for Jacobin magazine, which describes itself as the “leading voice of the American left.”

Parenti charts the historical process through which racialized violence has manifested itself in America, and argues that it is only within the last 40 or so years that the criminal justice system has become central to this process.

He wrote: “For the better part of a century after the end of Reconstruction in the 1870s, the national incarceration rate hovered at around 100 to 110 per 100,000. But then, in the early 1970s, the incarceration rate began a precipitous and continual climb upward.”

Parenti argues that the expansion of criminal justice came on the heels of “the society-wide rebellion of the late 1960s.” Police brutality and the prison state, he asserts, are a reaction to the “crisis” of the civil rights movement, challenges to corporate power, and the capitalist system as a whole.

Debate over the nature of criminal justice and police brutality is being debated daily on every major news channel, and this debate has reached the highest rungs of the political elite. President Barack Obama is even starring in a Vice special on America’s criminal justice system, slated to air on Sept. 27.

However, Parenti wrote:

“Incarceration rates have begun to plateau again, and there are growing divisions among economic and policy elites about the nation’s grotesquely overgrown justice system. California, under court order, has released more than forty thousand prisoners in recent years. This indicates an opening that movements like Black Lives Matter can exploit to force through meaningful policy changes.

And what is our side’s policy prescription? Less. Not better, just less. Fewer prisons, fewer SWAT teams, less surveillance. Not better-trained cops with body cameras, but rather less gear, less money, and fewer cops.”