When a brand-name drug to help prevent premature births was approved last year, its $1,500-a-dose-price alarmed state and private sector insurance officials.

Many restricted use of the FDA-approved Makena in favor of $20- to $40-a-dose versions that had been made for years by pharmacies, saying that would give more women access to the treatment. Federal officials, sympathetic to such arguments, allowed the pharmacies to continue making the unapproved drugs.

But those decisions are now getting a second look following a deadly meningitis outbreak linked to a different pharmacy-made drug that has sickened hundreds of people and killed 25. No one has been reported injured by the pregnancy drug knockoffs. But the judgments made about Makena offer a window into the difficult tradeoffs between cost, safety and access sometimes confronted by policymakers and insurers at a time of growing angst over drug prices.

They also highlight the increased role of these pharmacies, some of which have begun to function as de facto drug manufacturers mass producing treatments for asthma, menopause and pain, among other conditions, but with far less oversight.

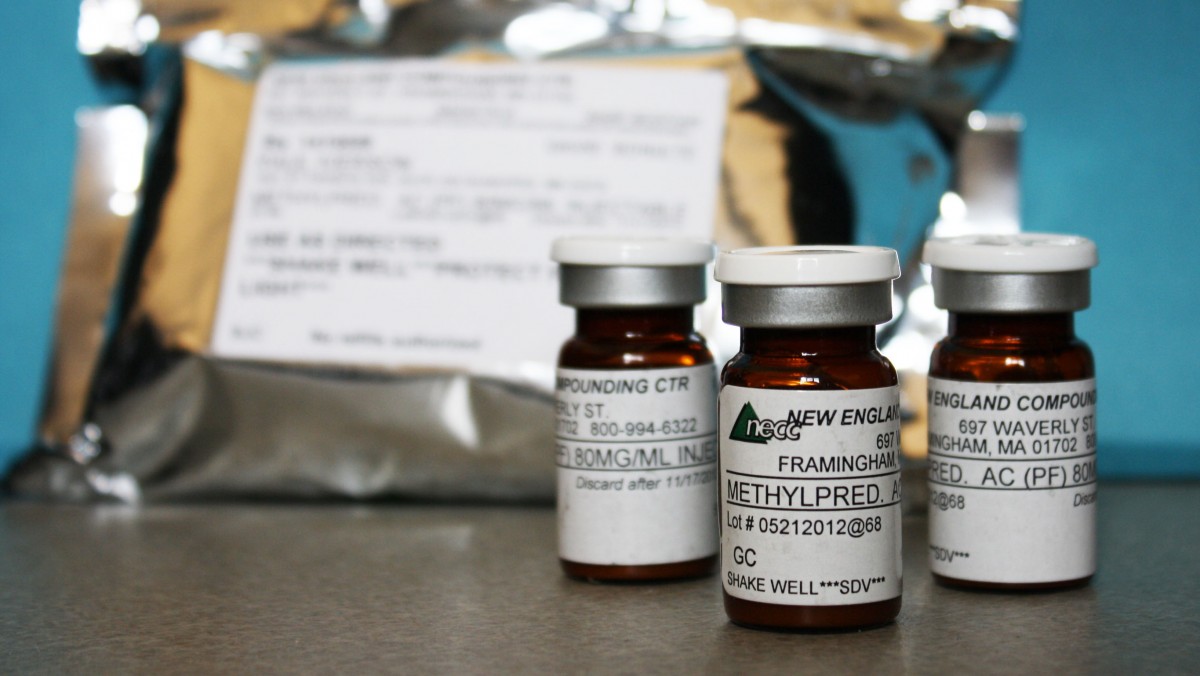

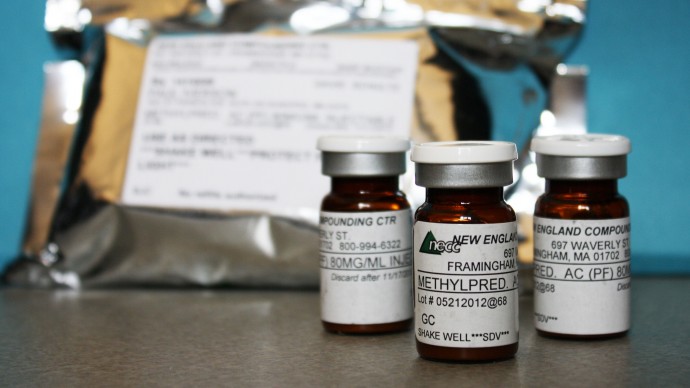

Vials of a compounded version of the injectable pregnancy drug were among the dozens of products recalled by the now-shuttered New England Compounding Center (NECC) in Framingham, Mass., believed to be the source of the fungus-contaminated steroids linked to the meningitis outbreak. Experts say contracting meningitis from the pregnancy drug is unlikely because it’s administered into muscle, not the spine. But a contaminated dose “could cause a local infection,” said Centers for Disease Control and Prevention spokesman Curtis Allen.

More significantly, potency problems might make the drug less effective in preventing a premature birth.

Earlier this year, the FDA investigated complaints by the brand name drugmaker, KV Pharmaceutical, about the quality of some pharmacy-made products. Testing a small number of samples, the agency said in June that a few failed potency tests, but there were no “major safety problems.” At the same time, it advised that “approved drug products, such as Makena, provide a greater assurance of safety and effectiveness than do compounded products.”

That didn’t shake the faith of at least a half dozen state Medicaid programs and some large private insurers, which continue to pay for the less expensive compounds.

Alabama Medicaid officials say they had “not one problem” with the pharmacy-made versions, although they recently began covering Makena after getting deeper discounts from the drugmaker, said Kelli Littlejohn, director of clinical services and support for the state’s Medicaid program.

Neither the federal agency that oversees state Medicaid programs, the state Medicaid directors association, the drug manufacturer or doctors’ groups could say how many state programs restrict access to the FDA-approved drug.

Backlash Over Makena’s Price

Up to 150,000 women in the U.S., at risk of having a repeat pre-term delivery, may be prescribed Makena or the pharmacy-made versions of the progesterone drug. The drug does not prevent premature birth in all those who take it. Tests leading to Makena’s approval found that 37 of 100 women taking Makena still delivered prematurely. But that was an improvement over the control group. Of the 100 women not given the drug, 55 gave birth early.

KV, which did not develop the drug, purchased legal rights to it another firm for nearly $200 million, and won market exclusivity for seven years. It assumed state Medicaid programs — and private insurers — would cover the FDA-approved version and that it would soon recoup its investment.

Almost immediately, however, the drug’s price, called “outlandish” by a March of Dimes official, provoked indignation from doctors’ groups and some members of Congress. In late March, the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services advised state Medicaid programs that they could continue to pay for the cheaper versions of the drug, which have been available since about 2003. The agency did not return calls seeking comment.

On that same day, the FDA issued what many observers saw as an unusual statement, saying that “to support access to this important drug, at this time and under this unique situation,” it would not take enforcement action against pharmacies that properly and safely made similar versions of the drug.

In the past, the FDA had sent warning letters or pursued other action against pharmacies when it could show they were mass producing copies of FDA-approved drugs.

“The FDA does not usually recommend that patients use compounded versions of FDA-approved drugs,” pharmacists Yesha Patel and Martha Rumore say in an article in the July issue of P&T, a journal aimed at physicians, insurers, hospitals and others developing drug coverage policies.

Pharmacists who mix or “compound” drug formulations are allowed to make formulations for individual patients who can’t use traditional drugs, but not to mass produce compounds. They are generally overseen by state regulators, not the FDA.

Not long after the FDA statement, financially beleaguered KV lowered its price for Makena to $690 a dose — bringing the total cost to about $14,490 for a woman who needs 21 doses. For some Medicaid programs, that was still too much.

‘Out of Reach’

“Even at this price, it remains out of reach for state Medicaid programs and the women they cover,” Louisiana Medicaid leaders wrote in a letter to health care providers in April 2011. By covering the pharmacy-made version, they could ensure that more women would receive the treatment, reducing the number of pre-term births in the state. Health officials estimated that a premature baby cost the state Medicaid program $33,433 in the first year of life, versus $3,671 for a full-term infant.

Louisiana still requires doctors to get special approval to prescribe Makena.

Similarly, Texas doctors must show there is no pharmacy able to make or deliver the drug to their offices to get coverage. That policy is now under review, a spokeswoman said.

Before Kentucky doctors may use Makena, Medicaid requires them to show that a woman has had a bad reaction to the compounded version – or had previously tried it and delivered prematurely.

Doctors in Wisconsin must explain why a woman might have trouble with a compounded drug, while doctors in South Carolina must show medical necessity for the branded drug.

“Some of these policies are a little more subtle than others,” said Scott E. Goedeke, a senior vice president with Ther-Rx, KV’s marketing subsidiary. “But they have similar effects: Physicians who want to prescribe the FDA-approved Makena learn from experience that process is so difficult or prohibitive they may stop trying.”

Blaming those policies for its financial troubles – along with what it describes as the FDA’s failure to enforce its market exclusivity for Makena – KV has filed lawsuits against Illinois, South Carolina and Georgia, alleging that the rules expose Medicaid patients to “unapproved compounded versions … of uncertain quality.”

The company won a preliminary injunction against Georgia to keep it from enforcing the coverage rules. In August it filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, a month before its lawsuit against the FDA was dismissed.

Cheaper Versions Favored By Private Insurers

Insurers covering the private market, meanwhile, have a range of rules around the use of Makena. UnitedHealthcare, one of the nation’s largest insurers, says in a policy document that it “continues to support the use of compounded, preservative-free” versions of the drug through “local and national… pharmacies.” However, it also reimburses doctors who choose to prescribe Makena.

Cigna covers Makena, as well as the compounded drugs, according to an April 2012 policy document.

Still, some physicians may feel pressure to prescribe the cheaper versions even when the insurer says it will pay for the brand name drug.

“Most insurance companies say they cover Makena, but they also send letters advising us that in trying to keep down the cost of health care, we are strongly encouraged to use the cheaper alternative, which is the compounded drug,” said Michael Randell, an obstetrician/gynecologist in Atlanta. “Sometimes we can feel forced to comply with wishes of insurance companies, or they might retaliate and take us off their plan.”

Because Makena contains the same active ingredient, hydroxyprogesterone caproate, as the pharmacy-made drugs, there is little debate over whether the drugs are similarly effective – assuming the compounded version contains active ingredients that are mixed at the correct potency and under sterile conditions.

But as the investigation of NECC demonstrates, potency and purity problems have arisen with pharmacy-made drugs. Oversight of pharmacies is inconsistent at best.

A report this week by Massachusetts Rep. Edward Markey, a Democrat, described the unsanitary conditions there as “just the tip of an industry iceberg that has long needed reform and federal oversight.”

Last week, KV filed a complaint with the U.S. International Trade Commission alleging that the New England center and other pharmacies use active ingredients imported from Chinese factories that are not routinely inspected by the FDA.

Patient advocate Amy Allina at the National Women’s Health Network in Washington D.C. puts the blame on KV for overpricing Makena, but believes pharmacies making compounded medications need more oversight.

Noting that regulations follow “tragedies where people die,” she predicted the meningitis fatalities “could be the turning point for compounding pharmacies.”

This story was originally published by Kaiser Health News.